Republicans zigzag their way through conflicting convention messages

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The Republican National Convention should have come with a safety warning — beware of whiplash.

Throughout the first few days of their party extravaganza, Republicans zigzagged between conflicting messages in a frantic effort to bruise Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee who is leading President Trump in the polls.

Nowhere have the contradictions been sharper than in the party’s rhetoric on crime. Republicans promised to stand for “law and order” and warned that Democrats will empower “the vengeful mob that wishes to destroy our way of life.”

But they’ve also targeted Biden for pushing controversial legislation in 1994 that increased incarceration rates among Black men, crediting Trump for reforms that “made our system more fair and just for all Americans.”

Political parties are unwieldy, rambunctious organizations, and their conventions must be stretched to contain multitudes. Last week’s Democratic National Convention featured both Michael R. Bloomberg, a former Wall Street executive who became New York’s technocratic mayor, and Bernie Sanders, the rumpled democratic socialist senator from Vermont. Internal divisions are common during policy debates over how to expand healthcare coverage or tackle climate change.

Yet even by those standards, Republicans have contradicted themselves over and over this week. Many of the inconsistencies came as speakers tried to assure the country that the party is enlightened on racial issues even as it tries to stoke white voters’ fears.”

South Carolina Sen. Tim Scott, the only Black Republican senator, spoke about the outrage over the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor — one hour after an appearance by a white St. Louis couple who pointed guns at protesters passing by their St. Louis mansion.

“No matter where you live, your family will not be safe in the radical Democrats’ America,” said Patricia McCloskey, sitting next to her husband, Mark, in a wood-paneled room.

Corey Lewandoski, a campaign advisor, defended the McCloskeys for presenting an argument about “safety and security.”

“The McCloskeys did something a lot of Americans would do if they felt if they were potentially in jeopardy, whether it was real or perceived,” he said. “That has nothing to do with racism.”

Paris Dennard, the Trump campaign’s senior communications advisor for Black media affairs, rejected the idea that the convention’s speakers have been inconsistent.

“There are absolutely no contradictory messages about the safety and security of the American people, namely those living in urban cities where Democrat leaders refuse to put an end to lawless riots, violence and murders,” he said.

Dennard added, “Our message is consistent, and voters agree with us, which is why recent polling has showed Black Americans do not want less police presence in their neighborhoods because they know defunding the police will leave them less safe and secure.”

Biden has proposed boosting police funding as well as shifting additional resources to mental health counseling.

Nikki Haley, Trump’s former ambassador to the United Nations, spoke near the end of the convention’s first night about the aftermath of the massacre by a white supremacist at a church in South Carolina, where she was governor, in 2015.

After the shooting, Haley said the state “removed a divisive symbol, peacefully and respectfully,” a reference to pulling down a Confederate flag from the statehouse building.

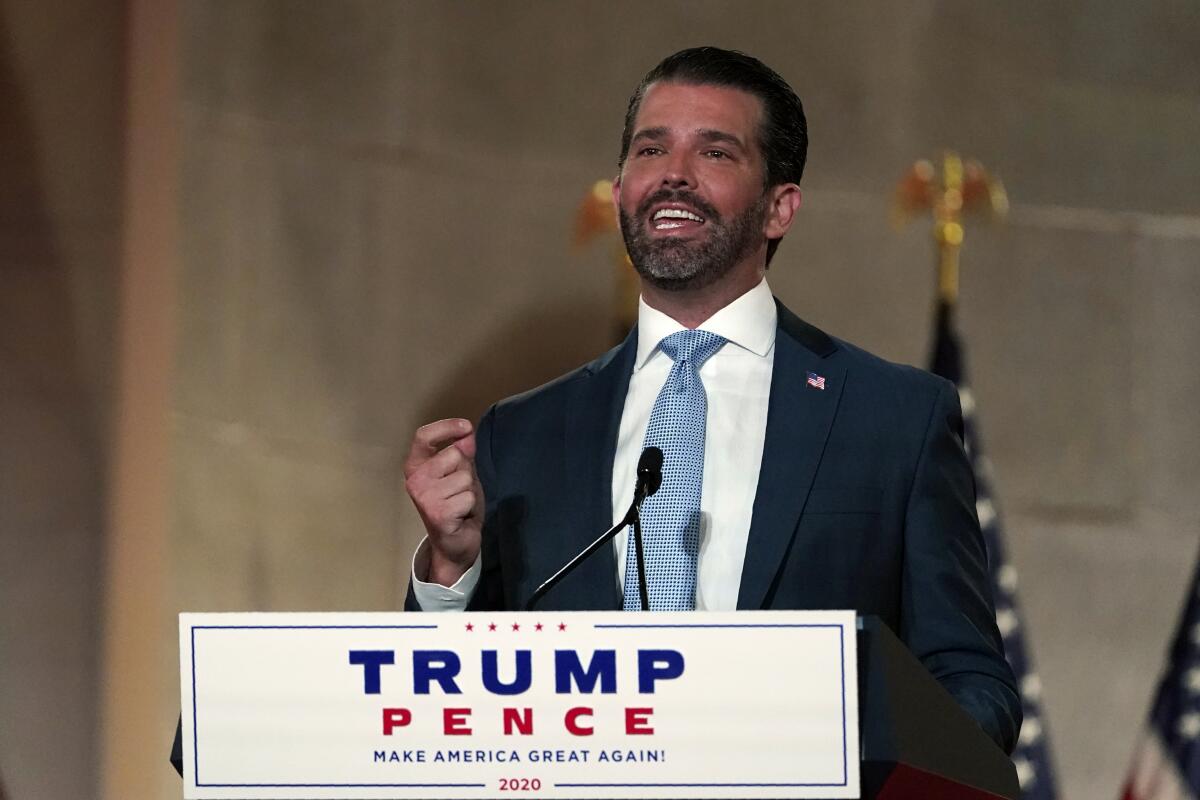

Next up was Donald Trump Jr. with a different message — he accused liberals of trying to erase the past.

“We’re not going to tear down monuments and forget the people who built our great nation,” he said.

Like Haley, Trump Jr. didn’t explicitly mention the Confederacy, but his comments placed him squarely on the opposite side of the issue.

The inability to maintain a consistent message reflects Trump’s struggle in tarring Biden as he did Hillary Clinton four years ago. During that campaign, he could capitalize on longstanding Republican attacks on Clinton, painting her as corrupt, untrustworthy and elitist.

No such framework exists for Biden, who is less prominent despite his decades in public service and enjoys more goodwill from voters.

Trump faces a similar problem with targeting Kamala Harris, Biden’s running mate. His campaign has alternated between describing the California senator as a liberal radical and blaming her for tough-on-crime policies when she was a prosecutor in San Francisco.

Republicans were quick to skip over inconvenient facts or accuse their opponents of the same offenses that they’ve committed.

At one point, Trump Jr. criticized “Beijing Biden” for being the favored candidate of the Chinese, citing a U.S. intelligence report that concluded China would prefer to see Trump lose. But he glossed over an adjacent conclusion that Russia was meddling in the campaign to undermine Biden — repeating its efforts against Hillary Clinton four years ago — and acting much more aggressively than China.

During a recorded appearance with front-line workers at the White House, Trump thanked a woman who delivered mail to a senior community during the coronavirus outbreak. Even though his administration has financially squeezed the U.S. Postal Service, which he has consistently attacked, the president promised that “we’re not getting rid of our postal workers.”

Then he added, “if anyone does, it’s the Democrats, not the Republicans.”

Trump has never been known for his skill at staying on message, a trait that endears him to his supporters but can frustrate allies who wish he would generate fewer distractions.

He veered off course in a meeting with former U.S. hostages who were held overseas. First up was Andrew Brunson, a pastor who became a cause célèbre while spending two years in detention in Turkey.

But even as Trump expressed satisfaction that Brunson was home, he had warm words for the country’s authoritarian leader.

“To me, President Erdogan was very good,” Trump said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.