Column: Trump’s bogus executive actions are reality TV, not governing

- Share via

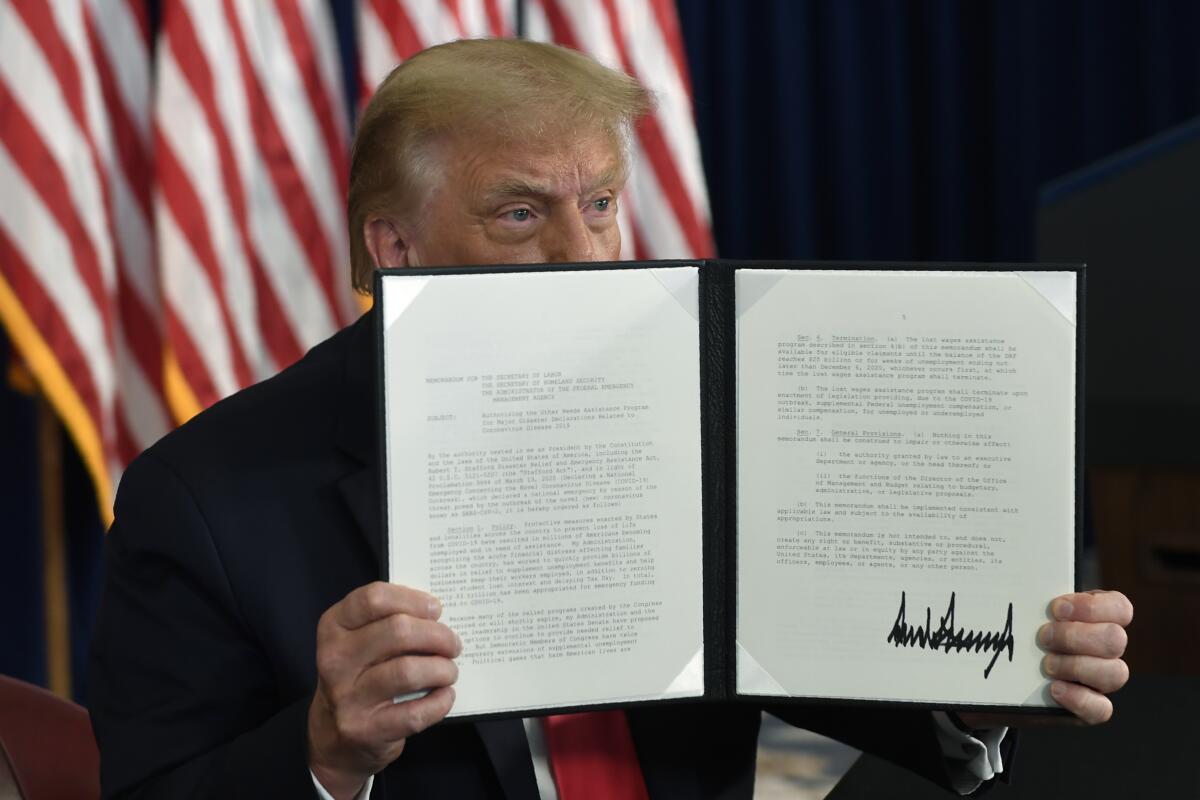

Last Saturday, in the clubhouse of his golf club in Bedminster, N.J., President Trump sat at a small table and signed four orders that he said would “take care of pretty much this entire situation” — his euphemism for the coronavirus recession that has thrown millions of Americans out of work.

Club members in Bermuda shorts and other golf attire applauded warmly. Television cameras recorded. Within hours, the president was rewarded with the headlines he sought.

“Executive action: the president goes around Congress to extend unemployment relief,” the NBC Nightly News began. “Sidestepping Congress, Trump Signs Executive Measures for Pandemic Relief,” the New York Times reported.

That was precisely the message Trump and his aides hoped to convey. “The American people … seek leadership, and President Trump delivered,” his press secretary, Kayleigh McEnany, declared.

Newsom and others called on federal officials to overcome a stalemate involving Congress and the president to provide additional funding for states.

Except he didn’t — not in the sense of effective action that could help struggling Americans or turn the economy around.

For months, the president has been on a rampage of executive declarations. He’s announced unilateral actions purporting to extend emergency unemployment benefits, reduce drug prices, protect patients with preexisting medical conditions, even punish those who attack statues.

Some of the actions, including the four at Bedminster, were assailed as unconstitutional by constitutional lawyers, angry Democrats and even a few Republicans.

But most harbor a deeper flaw: They’re bogus — little more than political theater designed to make the president look good.

They’re Potemkin government: announcements that pretend to do something but actually do very little.

Take his order at Bedminster to the Federal Emergency Management Agency to pay $300 per week to unemployed workers to replace the $600 federal payment that expired last month.

Trump said the total benefit would be $400 a week, but that number includes $100 from state coffers, which might come from existing unemployment benefits, or might not arrive at all.

States say they don’t have a system to handle the funds, and some say their unemployment plans are running out of money.

But even if the president’s order were put seamlessly into effect, experts say the $44 billion he has designated for the plan would last no more than six weeks. It’s hardly a solution to a deep recession forecast to extend well into next year.

Or take the president’s favorite measure, his decision to defer collecting payroll taxes — the taxes that fund Social Security and Medicare — on employees who make less than $100,000 a year.

It’s a straightforward middle-income tax cut, delivered weeks before voters begin filling out their mail-in ballots. Its political appeal is obvious.

But its economic rationale is flimsy. The tax delay would benefit people with jobs, not the hard-hit unemployed.

And the benefit would be short-lived; next year, the IRS would have to bill workers for the taxes they skipped, unless Congress found a different way to fund Social Security and Medicare. It’s one reason even Republicans have rejected the idea.

The president’s package also would allow about 35 million borrowers to skip payments on federally held student loans until the end of the year — another benefit that gets past election day, but not much beyond.

Trump’s most vaporous action was an order to federal departments to “prevent residential evictions and foreclosures resulting from financial hardships caused by COVID-19.” But he didn’t specify any actions; he merely told agencies to see what they could do.

“The housing order does absolutely nothing,” John Hudak, a governmental scholar at the nonpartisan Brookings Institution, told me.

That didn’t stop Trump’s chief economic adviser, former television pundit Larry Kudlow, from making a grandiose promise: “There will be no evictions,” he said.

And that’s the underlying problem with many of Trump’s executive actions: They over promise and under deliver.

It’s not that the orders are unconstitutional or illegal — although some may be.

It’s not that he’s resorted to unilateral action when his negotiations with Congress broke down; his predecessors, including Barack Obama, did that too.

It’s not even the hypocrisy of a man who once charged that Obama preferred playing golf to dealing with Congress, and now issues proclamations from his golf club. Trump has surpassed Obama’s pace of executive orders, issuing an average of 49 a year; Obama signed only 35 a year, according to the American Presidency Project at UC Santa Barbara.

The most striking thing about Trump’s executive orders is their transparent use to send political messages, especially in an election year.

Earlier presidents sometimes announced important orders from the White House; Trump is the first to make routine signing ceremonies into political theater, exhibiting his jagged signature as evidence of his power.

So give the president credit: He’s invented a new political art form — or at least stretched an old one to a new extreme.

The important thing is to appear to be doing something — whether the “something” is effective or not. It’s not governance, it’s reality television.

The danger he faces is that voters will notice if his promises don’t come true — if the unemployed don’t get the promised $300 benefit, if evictions don’t stop, if the pandemic continues to spread.

Grand declarations won’t substitute for real solutions — and Trump hasn’t offered any of those.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.