Coronavirus is America’s common enemy, but the states aren’t fighting as a team

In fighting the coronavirus pandemic, the U.S. is going to live and die by its decentralized public health system.

- Share via

As the pandemic has washed over the U.S., the coronavirus has faced an inconsistent set of defenses in recent weeks, with state borders often marking the difference between whether millions of Americans — and therefore the virus — are free to move about or not.

The lack of strong direction from the Trump administration has left many life-and-death decisions in the hands of state and local officials, whose varied response is projected to produce a notable disparity in rate of infection and how many lives are spared or lost.

Under the nation’s decentralized system of public health management, governors hold sweeping quarantine powers, making them marquee political figures. An early group, primarily Democrats, bucked the Trump administration in mid-March to shut down businesses and impose social distancing orders in the most disruptive government intervention into Americans’ lives since World War II.

“Federalism is America’s great strength and its greatest weakness,” said Lawrence O. Gostin, professor of global health law at Georgetown University. “When there’s a leadership vacuum, other leaders fill that void, and in this case, it’s been governors.”

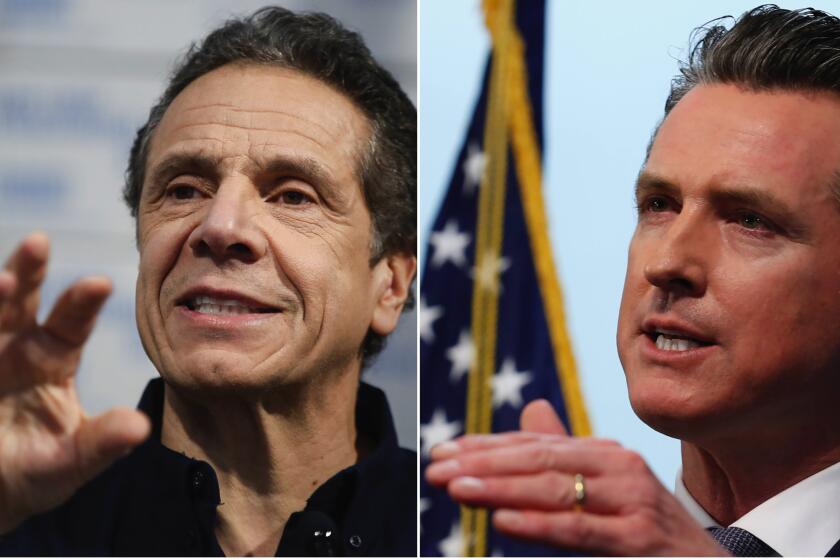

Democratic New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s daily briefings on his oversight of the nation’s worst outbreak zone have turned into must-watch TV for many Americans. At home, New Yorkers have rewarded his brusque, Gen. Patton-like style of public speaking with a practically dictator-like 87% approval rating.

In the age of coronavirus, Govs. Andrew Cuomo and Gavin Newsom have become the nation’s truth-tellers and consolers in chief.

“In this time of crisis, with little concrete information available, I need Cuomo’s measured bullying, his love of circumventing the federal government, his sparring with increasingly incompetent [New York City] leadership,” Jezebel writer Rebecca Fishbein wrote in a tongue-in-cheek appreciation titled, “Help, I Think I’m In Love With Andrew Cuomo???”

But apart from some early responders like Republican Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, other GOP governors matched President Trump’s hesitation. They failed to acknowledge the coronavirus as an imminent threat requiring intrusive measures such as stay-at-home orders, even as scientists warned that time is running out to blunt the virus’ spread.

Trump said Friday that he would not recommend stay-at-home orders nationwide. “I leave it up to the governors,” he said. “The governors know what they’re doing.”

“In a pandemic, when the nation has to act with one voice and one hand, [federalism is] an impediment,” Gostin said. “There’s just no sense in one state being rigorous and another state not, with people moving back and forth.”

Florida’s Republican governor, Ron DeSantis, who set up checkpoints on his state’s border to stop travelers from New York and Louisiana, had resisted issuing a statewide stay-at-home order on the grounds that Trump’s coronavirus team hadn’t recommended it.

“If they do, that’s something that would carry a lot of weight with me,” DeSantis said Tuesday.

DeSantis reversed course the next day after Trump had warned at a news conference that between 100,000 to 240,000 Americans could die in the coming weeks.

“When you see the president up there and his demeanor the last couple of days, that’s not necessarily how he always is,” DeSantis said Wednesday.

The spread of the coronavirus has shut down life at Florida’s retirement villages, where social clubs, private dining and golf courses are part of the appeal.

His fellow Republican to the north, Gov. Brian Kemp of Georgia, waited until Wednesday to issue his own stay-at-home proclamation, saying that “we didn’t know that until the last 24 hours” that asymptomatic carriers of the virus could infect other people — which scientists have warned about for weeks.

“If you look at what’s going on in this country, I just don’t understand why we’re not” mandating nationwide stay-at-home orders, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said on CNN on Thursday. “We really should be.”

After a surge of new directives in recent days, more than 40 states as of Friday had statewide stay-at-home orders, in some instances effectively expanding the orders already in place from many cities and counties that had shut down earlier.

One of the dwindling number of holdouts, Republican Gov. Kim Reynolds of Iowa, defended herself against Fauci’s comment, saying Friday “that maybe he doesn’t have all the information.”

“You can’t just look at a map and assume that no action has been taken. That is completely false,” Reynolds said, noting that she had done other distancing measures such as shutting down dine-in restaurants and banning large gatherings.

Much like today’s battle against the coronavirus, when the United States faced the great influenza pandemic of 1918, there wasn’t much united about the country’s response.

What archives in L.A. devoted to 1918 Spanish flu can teach us about coronavirus

President Woodrow Wilson’s administration had little appetite for battling a pandemic during World War I, leaving local officials to come up with their own directives. By the time they shut down public spaces to separate residents, it was often too late.

Cities that acted quickly and consistently, such as St. Louis, were spared the worst of the disease, while others that didn’t, such as Philadelphia, were devastated. The virus killed about 675,000 people in the U.S.

“1918, there was no national strategy,” said John M. Barry, author of “The Great Influenza.” He added grimly of today’s coronavirus response: “What we learn from history is that we learn nothing from history.”

The federal government has far more scientific tools than it did in 1918, with agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and experts such as Fauci, serving as key clearinghouses for guidance on how to battle pandemics.

During the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic, “everyone looked to the CDC for guidance” and reacted accordingly, said J. Alexander Navarro, assistant director at the Center for the History of Medicine at the University of Michigan, who studied the reactions of state and local health officials. Federal health officials deemed the virus less deadly than initially feared, and local officials did not pursue widespread social distancing policies as a result.

“The general lay public expects that in times of national crisis like this that there would be one single federal response, and they’re kind of shocked when they learn that’s not how public health works in the United States,” Navarro said. “That’s just not the way the system is set up.”

After Trump took office in 2017, his administration moved to cut back many of the federal government’s anti-pandemic programs. While cases of the new coronavirus started quietly multiplying in the U.S. as early as January this year, the president spent weeks downplaying the virus — saying on Feb. 28 that the virus would disappear like a “miracle” — setting the stage for a remarkable rebellion by state officials, who were watching reports of the spreading contagion with alarm.

The program had worked with labs in Wuhan, China, and around the world to detect deadly viruses that could jump from animals to humans.

“The states couldn’t wait for the federal government to come around,” Navarro said. “They needed to act. ... The states that had been hit first, they had been pretty vocal about how chaotic the federal response had been.”

Several governors plunged into action in mid-March, issuing wide-ranging shutdown orders even as Trump pushed back, saying he wanted Americans back at work by Easter.

The relatively uncoordinated federal response — and Trump’s reluctant invocations of the Defense Production Act to order private industry to make more safety equipment such as masks and ventilators — has also unleashed some bidding wars for equipment between states, reportedly driving up costs at a time of rapidly shrinking budgets.

“It’s like being on EBay, with 50 other states bidding on a ventilator,” Cuomo said at a news conference last week, adding that the Federal Emergency Management Agency had now also joined in. “What sense does this make?”

Democratic Washington Gov. Jay Inslee, best known for his previous calls for a mobilization of the economy to fight climate change, is now urging companies in his state to take action.

“We can’t depend on being rescued here,” Inslee said Wednesday, calling for state manufacturers to produce safety and testing gear to help fight the coronavirus. “We have to do self-rescue. We have to be committed to our own destiny.”

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom, at times referring to California as a “nation-state” during the crisis, has sniped at the federal government for sending broken ventilators for COVID-19 patients but then boasted of his own state’s ability to fix the equipment.

“That’s the spirit of California,” Newsom said. “That’s the spirit of this moment.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.