Democrats gear up for brutal 2020 fight with Trump in Michigan

- Share via

STERLING HEIGHTS, Mich. — Democrats in Michigan have been mobilizing for months for a fierce general election fight against President Trump, determined not to lose this Midwest battleground as they did in 2016.

Even before they know who their nominee will be, Democratic groups are pouring millions of dollars into anti-Trump ads here, portraying the Republican president as an unstable leader who threatens Americans’ healthcare and the nation’s security. A network of progressive groups across Michigan has already identified voters susceptible to voting against Trump and started reaching out to them on issues they care about most.

Michigan’s presidential primary — the biggest of six Democratic contests Tuesday — will test the appeal of former Vice President Joe Biden and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders in a state likely to play an outsize role in deciding whether Trump wins a second term.

If Democrats are to recapture Michigan, voters in this Detroit suburb in the heart of bellwether Macomb County will be key.

The predominantly white county backed President Obama’s reelection in 2012 after an auto industry bailout that kept the region’s top employers — and their many suppliers — in business. But in 2016, it chose Trump over Hillary Clinton. Trump’s combative rhetoric on immigration and trade resonated with its working-class voters, and so did his disruption of the political establishment.

“I support him, because I’m sick and tired of the same old, same old,” Jack Shaw said recently as he downed chicken wings and beer at Gator Jake’s Bar & Grill.

The induction tooling salesman has backed Democrats in the past, but he voted for Trump and plans to do so again. He credits the president for the many “Help Wanted” signs around Sterling Heights.

In 2016, Trump played both to voters’ deep resentment over the region’s troubled economy and to its fraught history of racial tension, said Democratic consultant Joe DiSano, a Macomb County native. “He uncannily tapped into it and continues to do so,” DiSano said.

The question now is whether Trump retains enough appeal among white working-class voters in communities ravaged by industrial decline to win the state again. Whether Democrats draw a strong turnout of black voters could also be decisive.

The number of manufacturing jobs in Michigan has plummeted over the last two decades from 888,000 to 631,000. After the Great Recession, a regionwide recovery during the Obama years continued under Trump, but lately the trend has turned downward in manufacturing — contrary to the president’s boasts.

The devastation of Michigan’s economic struggles is still striking in Detroit, where thousands of abandoned houses and boarded-up businesses mar much of the cityscape despite a revival downtown. Factory closings and downsizings have driven Detroit’s population down by 1 million people from its Motown heyday in 1960.

“We have not come close to gaining back all of the manufacturing jobs we lost,” said Gabriel Ehrlich, an economic forecaster at the University of Michigan. He attributed the most recent troubles to slowing vehicle sales, Trump’s trade war and a strong dollar that makes U.S. exports more costly.

Trump’s victory here in 2016 was thinner than in any other state: He beat Clinton by fewer than 11,000 votes of 4.8 million cast. Trump’s narrow wins in Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania gave him an electoral college victory even as Clinton carried the national popular vote, 48% to 46%.

This time, Democrats are determined not to take Michigan for granted, as many believe Clinton did until the closing days of her campaign. She was the first Democrat to lose the state’s presidential vote since Michael Dukakis in 1988.

“People know that Michigan matters and, quite frankly, four years ago they didn’t,” said Rep. Debbie Dingell, a Democrat who represents working-class suburbs west of Detroit.

The Democratic super PAC Priorities USA is spending nearly $6 million on anti-Trump television ads that start running this month in Detroit, then later this spring in Flint, Grand Rapids and other parts of Michigan. The group’s initial spot focuses on the president’s provocative tweets and unpredictable behavior. “I have a right to do whatever I want as president,” Trump says in the ad.

“We cannot allow Trump and his campaign to define the election in a critical state like Michigan before we even have a nominee,” said Patrick McHugh, executive director of Priorities USA.

Beyond the advertising, a wide array of local groups — among them, a network of suburban women known as Fems for Dems — already has begun groundwork, with activities such as phone banks and door-to-door canvassing to promote candidates for all offices on the 2020 ballot.

“That’s really an important piece of the puzzle,” said Amy Chapman, a party strategist who was state director for Obama’s 2008 campaign.

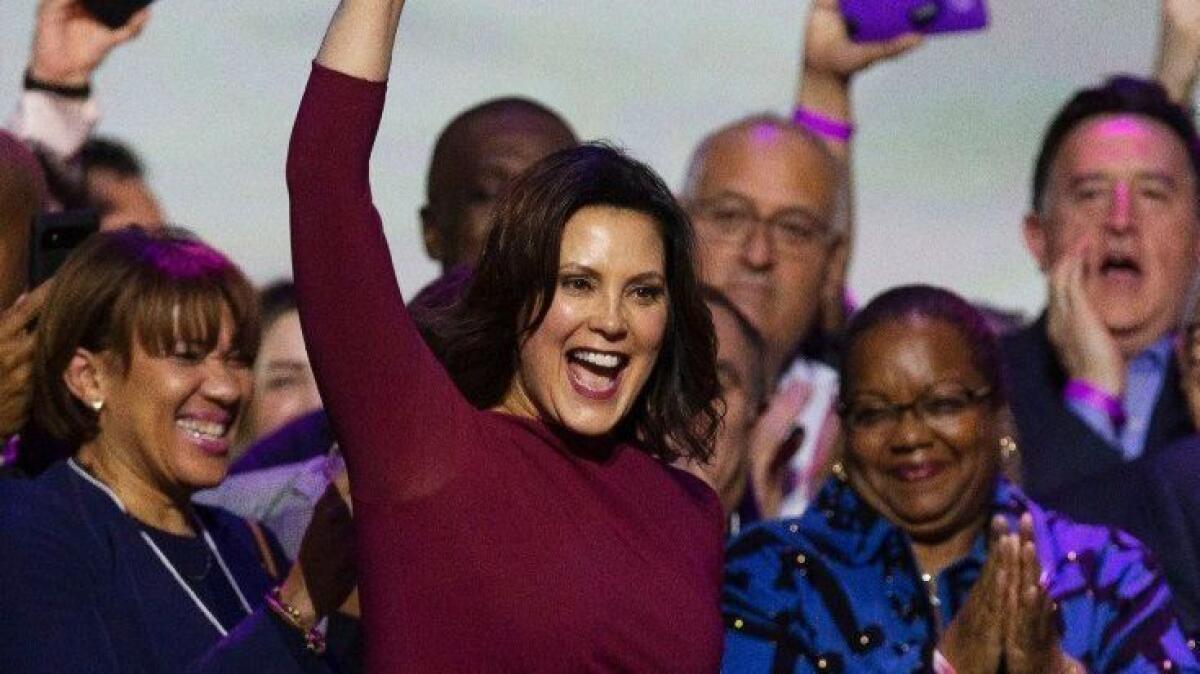

In 2018, such groups were crucial to Democratic women capturing three statewide offices — including the governorship for Gretchen Whitmer, who recently endorsed Biden — and two U.S. House seats. The groups also helped pass a ballot measure that eased access to voting.

Still to be determined for 2020 is what happens to the more than 100 staffers hired to work in 10 offices across Michigan for Michael R. Bloomberg, who dropped out of the Democratic presidential race on Wednesday. The former New York City mayor, a billionaire who spent more than $660 million on his campaign and now supports Biden, has vowed to keep in place much of his roughly 2,500-person staff to work against Trump’s reelection.

“We’ll be here for the long haul,” said Carol Banks, Bloomberg’s regional director for eastern Detroit.

Banks supervised an office full of people working the phones for Bloomberg in a former Detroit karate studio. It was still open on Thursday, but it was not yet clear how Bloomberg would shift its mission to defeating Trump.

“We have not gotten any instructions or directions,” said Banks, who is on Bloomberg’s payroll until November.

Bloomberg spent more than $14 million on advertising in Michigan, much of it on TV commercials attacking Trump, according to Advertising Analytics, a media tracking firm.

Biden and Sanders are now both running ads aimed at Michigan’s working class. A Biden spot shows him visiting a car assembly plant as Obama says his vice president “revitalized American manufacturing as the head of our middle-class task force.”

Taking a more combative approach, a Sanders ad attacks Biden for supporting the North American Free Trade Agreement. “The community has been decimated by trade deals,” autoworker Sean Crawford says as images of boarded-up factories and houses flash by.

Biden, who planned to campaign Monday in Detroit and Grand Rapids, had no offices or staff in Michigan as last week began, reflecting his trouble raising money before his victory in South Carolina propelled his dramatic Super Tuesday rebound. By Tuesday, “double-digit paid staff” had arrived in Michigan, a Biden spokeswoman said.

Sanders, who held four Michigan rallies over the weekend, opened offices around the state months ago and assembled a big network of volunteers.

Trump, too, has assembled a sizable operation, with 30 staffers working in the state, said Rick Gorka, a spokesman for Trump Victory, a joint effort of the president’s campaign and the Republican National Committee. “The key aspect of our operation in Michigan is we never left,” Gorka said.

Using its elaborate data bank, Trump’s team is focused on maximizing turnout of rural white voters. Trump and Vice President Mike Pence have repeatedly campaigned in Michigan. In December, Trump railed against Democrats at a rally in Battle Creek on the night he was impeached.

Pence told a farmers group in Lansing last month that “the era of economic surrender to China is over,” and boasted of Trump’s preliminary trade deal with President Xi Jinping. The campaign is sensitive to maintaining support among farmers, many of whom have lost business in the trade war.

Trump has also tried to win over black voters, at least enough to cut into Democrats’ typically huge margins. His campaign is opening community centers in black neighborhoods of Detroit and other cities, and he often talks about sentencing reforms he signed into law.

Some Democrats fret about a recurrence of tepid turnout among black voters, which hurt Clinton in 2016. Others see Trump’s gestures as empty.

“We are not going to be fooled by these trappings of sensitivity,” said the Rev. Wendell Anthony, who heads the Detroit NAACP.

African American voters in Detroit are fired up to beat Trump. But they want some love from the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates.

More challenging for Democrats are white working-class voters in places like Sterling Heights. Joining Shaw at Gator Jake’s on Saturday was his friend Bill Dietz, a retired Chrysler stamping plant supervisor.

Dietz, 73, didn’t vote in 2016 but approves of the job Trump is doing, particularly his tough and unpredictable posture on the world stage. “At first, I didn’t want a guy like that close to the button,” he said. “But now I don’t know. Maybe he’s scaring the other guys.”

Ken Jackson, an English professor at Wayne State University in Detroit, grew up in Macomb County. He sees Trump’s swagger as a big part of his appeal to white working-class voters here, including many whose families fled Detroit for the suburbs in the “white flight” that began amid the racial tensions and riots of the 1960s.

“A lot of that aggressive banter is very deeply connected to the cultural habits and speech patterns of these folks,” Jackson said. “That’s something they’re quite comfortable with. They associate that with authenticity and truth-telling.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.