Chief Justice Roberts presided impartially, yet left questions whether Trump’s trial was a fair one

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. stood stiff and tight-lipped, no hint of a smile, as President Trump stopped to shake hands Tuesday evening in the House chamber, just prior to his State of the Union address.

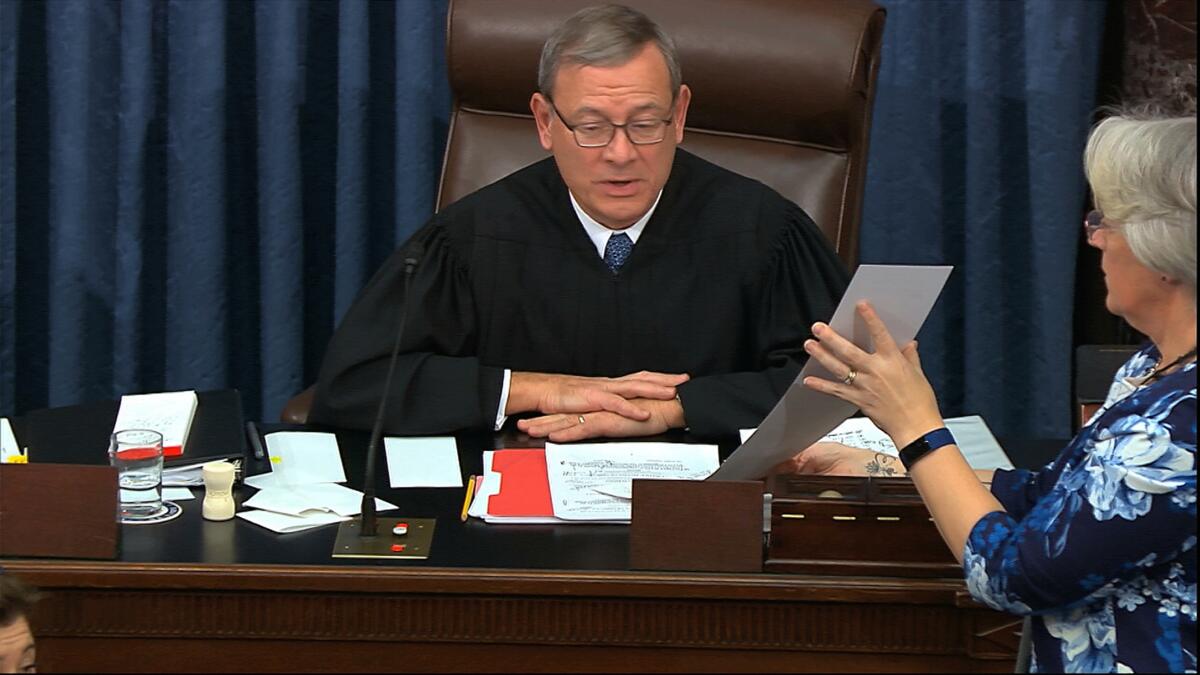

Roberts’ expression fit the role he had played through the long days of Trump’s Senate impeachment trial, only the third in history. The chief justice had been determined to preside as a strictly impartial judge over the highly partisan fight, much as his predecessor, William H. Rehnquist, did two decades before when President Clinton was tried and acquitted.

By that measure, Roberts accomplished his goal, legal experts said.

“I think the chief justice did a superb job,” said Jeffrey Rosen, president of the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia. “He fulfilled his plan of following the model set by Chief Justice Rehnquist, who had said, ‘I did nothing in particular and I did it well.’ On matters of civility and decorum, he chastised both sides equally for falling short of the standards of civility, and he avoided any hint of partiality.”

For 12 days, Roberts sat mostly quiet in his black robes while the House Democrats and Trump lawyers took turns arguing for and against the House’s charges that the president abused his power and obstructed Congress. He refused to read a question from Sen. Rand Paul (R-Ky.) revealing the administration whistleblower’s name. Otherwise he issued no rulings of consequence.

“He was at the best the Senate’s crossing guard — or perhaps the traffic cop when he admonished the parties to stay civil,” said Sarah Binder, an expert on Congress at the Brookings Institution in Washington.

Yet Democrats and many liberal activists were left angered that Roberts, by his passivity, presided over a trial forever tainted, as they see it, by the failure to consider witnesses and documents that bore directly on Trump’s alleged pressure against Ukraine to investigate a political rival, former Vice President Joe Biden.

“The American people wanted a fair trial, but — denied the testimony of firsthand witnesses and the evidence of still-blocked documents — the Republican-led Senate refused to give them one. And Roberts sat quietly looking on,” said Elizabeth Wydra, president of the Constitutional Accountability Center, a progressive group. “Fair or not,” she added, Roberts will be seen by many Americans “as just another conservative going along passively with what’s best for the Republican president rather than our country and the Constitution.”

Others, however, rejected the view that the chief justice should be faulted for how the Senate chose to conduct its trial.

“If I were the chief justice, I would have viewed this as a question for the Senate, not a question for the chief justice, because I view impeachment as fundamentally a political, not a judicial, process,” said Irv Gornstein, director of the Supreme Court Institute at the Georgetown University Law Center. “The chief justice wants very much to preserve his image and the image of the court as nonpartisan. The best way to do that in this circumstance is to leave the political questions to politicians.”

Harvard law professor Richard Lazarus, a Democrat and a friend of Roberts’ since law school, who sometimes teaches a class with him during the court’s summer break, said, “Perhaps not surprisingly, I think he did an excellent job under perilous conditions.”

“Would I personally prefer to see Donald Trump convicted by the Senate? Yes,” Lazarus said. “But that was not the chief’s job. That was the Senate’s job. And the chief did his job well. The Senate did not.”

Roberts’ one near-brush with controversy came Friday, but he resisted being drawn into the clash. The Democrats had pressed for the Senate to call witnesses to testify, including former national security advisor John Bolton and acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney. Both could have testified about their conversations with the president, pertaining to why the administration blocked nearly $400 million in military aid that Congress had approved for Ukraine, and whether the delay was tied to Trump’s insisting that the Ukrainian president first announce a Biden investigation.

At one point, as senators asked questions of the lawyers for both sides, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) posed hers for Roberts to read aloud. It suggested that he shared the blame for blocking witnesses.

Roberts stoically read the question just as he had others: “At a time when large majorities of Americans have lost faith in government, does the fact that the chief justice is presiding over an impeachment trial in which Republican senators have thus far refused to allow witnesses or evidence contribute to the loss of legitimacy of the chief justice, the Supreme Court and the Constitution?”

Answering Warren for the Democratic House managers, Rep. Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank) diplomatically said he did not accept her premise. “Senator, I would not say that it contributes to a loss of confidence in the chief justice. I think the chief justice has presided admirably,” Schiff said.

But he and other Democrats insisted the Senate could not have a fair trial without hearing from witnesses, and Minority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) forced a vote on calling for several to appear. Republicans warned they would counter by calling Biden and his son Hunter Biden. Schiff said Roberts could settle the matter by ruling that only witnesses with “relevant” testimony — Bolton and Mulvaney, as Democrats saw it, but not the Bidens — should testify.

If four Republicans had joined the 47 Democrats to approve Schumer’s motion, the chief justice could have found himself in the middle of a prolonged and hard-fought trial. If three Republicans had agreed, producing a 50-50 tie, Roberts would have come under pressure from Democrats to cast the deciding vote.

Roberts was spared when two Republicans — Sens. Lamar Alexander of Tennessee and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska — said they would vote with their party to defeat the motion. Murkowski said she did so in part to protect Roberts from being dragged into the partisan battle.

“It has also become clear some of my colleagues intend to further politicize this process, and drag the Supreme Court into the fray, while attacking the chief justice,” she said. “We have already degraded this institution for partisan political benefit, and I will not enable those who wish to pull down another.”

Schumer then posed a question of whether the chief justice, under any circumstances, would vote to break a tie. Roberts appeared to have prepared an answer. “If the members of this body, elected by the people and accountable to them, divide equally on a motion, the normal rule is that the motion fails,” he said. “I think it would be inappropriate for me, an unelected official from a different branch of government, to assert the power to change that result so that the motion will succeed.”

With the Friday evening votes clearing the way, the Republican-controlled Senate ended Trump’s trial Wednesday with the president’s acquittal by near-party-line votes. In adjourning the trial, Roberts invited the senators to visit the court just across the street, saying, “I look forward to seeing you again under happier circumstances.”

As he returns to the Supreme Court, however, the chief justice will have further opportunities to rule on the president’s interests in the months ahead.

The justices will decide whether Trump may repeal the Obama-era order that has protected nearly 800,000 young immigrants, who came to the country as children, from deportation. The court heard arguments in October, and a ruling should come in the next few months.

On March 4, the court will hear arguments in a Louisiana abortion case to decide whether state regulators may shut down all but one of the three remaining abortion clinics in the state. Trump’s lawyers are backing the state.

And on March 31, the court will hear Trump’s appeal of three lower court rulings that said the president can be forced to disclose his tax returns and financial records to House committees and state prosecutors.

The arguments will have a familiar ring for the chief justice. Jay Sekulow, one of Trump’s personal lawyers in the Senate trial, is arguing that the Constitution shields the president from subpoenas issued by House Democrats.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.