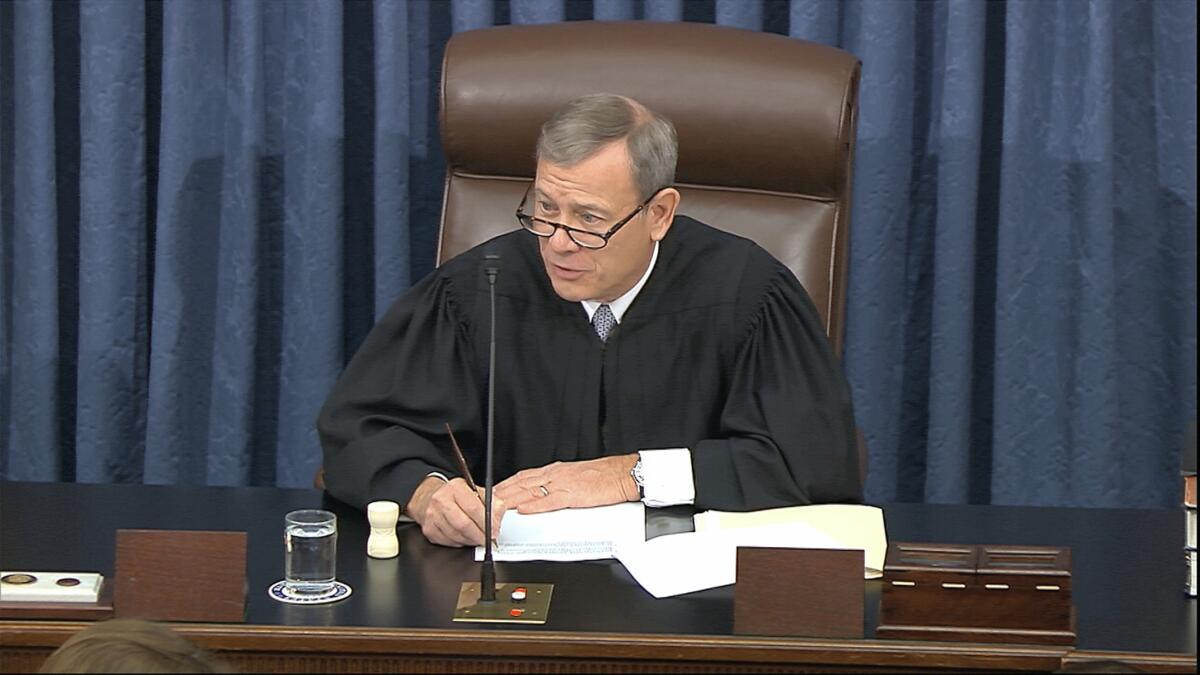

Even at 1 a.m., Chief Justice Roberts insists on Senate decorum at Trump impeachment trial

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. had sat patiently through nearly 12 hours of back-and-forth arguments in the Senate impeachment trial of President Trump when tired, increasingly edgy speakers on both sides began to grow louder and sharper around 1 a.m. Wednesday.

New York Democratic Rep. Jerrold Nadler, one of the House managers, accused the Republican senators of “voting for a cover-up” by rejecting Democratic motions to call witnesses. “Obviously a treacherous vote,” he said.

White House Counsel Pat Cipollone unloaded on Nadler. “The only one who should be embarrassed, Mr. Nadler, is you.”

Roberts, who is unfailingly polite and courteous in presiding at the Supreme Court, had heard enough.

“It is appropriate at this point for me to admonish both the House managers and the president’s counsel in equal terms to remember that they are addressing the world’s greatest deliberative body,” he said. There, members “avoid speaking in a manner, and using language, that is not conducive to civil discourse.”

He noted that in the 1905 trial of Judge Charles Swayne, who was impeached but acquitted of charges that included improper use of a private railroad car, a House manager was rebuked for using the word “pettifogging.”

“I don’t think we need to aspire to that high a standard,” Roberts said, “but I do think those addressing the Senate should remember where they are.”

Coming so close to the end of a nearly 13-hour session in which Roberts had said nothing beyond the perfunctory procedural remarks required of his post as presiding officer, Roberts’ polite smackdown surprised but also pleased senators from both parties, who said it set the right tone.

“I thought his admonishment was very balanced. He made a very clear point, but it fell equally on both sides. I think it sends the right signal,” said Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.).

“It was a good thing for the chief justice to do on the first day,” said Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.).

If anyone there had reason to be frustrated and testy it was Roberts. The chief justice began his official day at 10 a.m. Tuesday, when he and his Supreme Court colleagues took their seats to hear arguments on whether a small-time Florida drug dealer with a gun deserved 15 years in federal prison under the Armed Career Criminal Act.

After the lunch hour, he was driven across the Capitol grounds to spend the rest of his day presiding over the Senate trial that will decide whether Trump will be removed from office for an abuse of power and obstructing Congress. He gaveled the Senate to a close at nearly 2 a.m., enduring debates and votes on 11 Democratic amendments that were all doomed to fail.

When Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) brought the session to a close, he said, “Mr. Chief Justice, I wanted to say on behalf of all of us, thank you for your patience,” prompting applause in the chamber. “Comes with the job,” Roberts responded.

Then at 10 a.m. Wednesday, the chief justice was back at the Supreme Court, emerging from behind the red curtain with his colleagues to hear arguments in a major church-state case. Roberts introduced the lawyers and showed no signs of weariness from his long night at the Senate. He asked several questions, but as usual, let the lawyers do most of the talking.

Despite some obvious differences in the two jobs, Roberts is playing a somewhat similar role in both places. In the high court as well in the Senate, he introduces advocates for both sides and lets them make their arguments. He strives for fair-mindedness and impartiality and is not one to dominate the debate.

Unlike in the high court, his role in the Senate is that of the presiding officer, not a judge who will make a decision in the end. He has no vote on whether Trump will be convicted or acquitted. It’s unclear whether he will have any substantive role in the trial. It is possible, but not likely, he will be called upon to decide a motion on whether witnesses will be heard or evidence introduced.

The last of the Democratic amendments proposed that the chief justice be given the job of deciding whether certain witnesses should be called to testify. “Let’s have a neutral arbiter,” said Rep. Adam B. Schiff (D-Burbank), the lead House manager in the Senate trial. “We have confidence the chief justice will make a fair, impartial decision.”

Jay Sekulow, one of Trump’s attorneys, objected. “With no disrespect to the chief justice, this is not an appellate court. It is the U.S. Senate.” With that, the roll was called, and the amendment was defeated, with all 53 Republicans voting no and all 47 Democrats and independents voting yes.

Should any hard legal question arise, the chief justice also has two trusted aides within the Senate. They are Jeffrey Minear, the longtime counselor to the chief justice, and law clerk Megan Braun, a graduate of Yale Law School and UC Irvine.

Within the court, by contrast, the chief justice has a powerful role both in deciding the cases at the high court and, equally important, deciding what issues and questions will be ruled upon by the court. In the Florida drug case, Shular vs. United States, Roberts will lead the discussion when the justices meet later this week to decide whether to affirm or reverse the 15-year sentence.

The chief justice’s double duty is unlikely to have any direct effect on the high court, however. For one thing, the court has a scheduled recess that extends through the first weeks of February. The justices do, however, have a private conference on Friday morning to weigh dozens of pending appeals. On Monday morning, the court is likely to issue decisions. And Roberts will probably have a full day in the Senate. He will also mark his 65th birthday.

However, his duties in the impeachment trial are not expected to interfere with Roberts’ ability to write Supreme Court decisions. If Roberts is in the majority, he will assign one of his colleagues to write an opinion, a process that could take several months. Typically, justices assign one of their clerks to write a draft. Roberts is a particularly careful writer and likes to draft most of his opinions in longhand.

The court’s public information office said last week it expected no changes in the court’s schedule even if the trial lasts for weeks. “It should be business as usual at the court,” the statement said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.