Candidates’ talk of ‘Medicare for all’ makes some unions nervous. Here’s why

- Share via

LAS VEGAS — The Culinary Health Center is a beige, two-story office building on Las Vegas’ east side, miles from the casino glitz of the Strip and not much to look at by Sin City standards. The surprise is what happens inside, and how it gets paid for, which would probably make most American workers’ jaws drop.

On a recent Friday, the parking lot was full as union members and their families visited the facility for primary and pediatric checkups, dental procedures and eye tests and eyeglasses, almost all of which are offered at no cost. There’s no emergency room, but X-ray, ultrasound and CT scan equipment awaited use in the building’s 24-hour urgent-care wing, free of cost to union members, along with a pharmacy that offers free generic medications.

In the hallways, there are few markings indicating the facility is operated on behalf of the Culinary Workers Union Local 226, which represents 60,000 hotel and casino workers in the early-caucusing and general election swing state of Nevada. But there’s a phrase printed on the front door symbolizing the powerful union’s pride in its unique healthcare setup: “Exclusively ours.”

“I love it. I love it. Everything, one-stop shop. Great doctors,” Kimberly Williams, 45, a guest room attendant at the Bellagio for 15 years and a volunteer organizer for the union, said of the center. “I have had other insurance before, but I believe my Culinary insurance is the best, and I want to keep that.”

The labor movement has long pushed for more comprehensive government healthcare in the U.S. But to see why some unions are nervous about talk of “Medicare for all” in the 2020 Democratic presidential primary, there’s no better place to start than the Culinary Union, whose parent union, Unite Here, has waged aggressive strikes and contract campaigns with employers to secure a level of affordability, accessibility and autonomy over healthcare coverage that would be unrecognizable to most Americans.

Instead of receiving health insurance directly through their employers, Culinary Union workers and many Unite Here members across the country receive health insurance through Unite Here Health. It’s a multi-employer nonprofit trust jointly run by Unite Here and by unionized companies that have agreed, however grudgingly, to sign on to the fund and its union-negotiated plans — which put the overwhelming burden of paying for healthcare onto companies, not workers.

American workers, on average, pay for 18% of the cost of a single-coverage plan and 29% for a family-coverage plan, with employers picking up the rest, according to a recent survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation. Unite Here Health, by comparison, gets just 3% of its funding from union workers, according to the union’s financial statements. (Some other unions have similarly structured multi-employer plans.) Unite Here Health also operates the Culinary Health Center and other facilities in Chicago and Atlantic City.

As Democratic presidential candidates compete for coveted labor union endorsements that can bring an infusion of campaign resources and manpower, they are not the only ones on edge.

So as Democratic presidential candidates court the support of the Culinary Union, which is famed for the effectiveness of its election turnout operations in Nevada, the union has not been subtle in sharing its skepticism about the type of Medicare-for-all platforms advanced by Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont and Sen. Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts. Those proposals, which aim to replace private employment-linked insurance plans with universal government insurance, would almost certainly reduce the amount of control some unions have over their health insurance.

“If you’re telling anybody that they have to give up something they like for something they don’t know, that’s a pretty hard sell,” D. Taylor, the president of Unite Here, said in an interview.

The healthcare question has been posed at every town hall that Democratic candidates have held at the Culinary Union’s headquarters in Las Vegas.

“My brothers and sisters of the Culinary have been fighting for this health insurance for 84 years, fighting hard, and we’re still doing it,” Cristhian Barneond, a cook and a shop steward at the Cosmopolitan hotel, told Warren during her appearance on Dec. 9. “My question for you is, what is your plan to make sure we keep our Culinary health [insurance] intact?”

Warren said she had toured the Culinary Health Center and was “knocked out” by the arrangement. “What you’ve got is something I want to see replicated all around America,” Warren said of the union’s clinic. “The part that changes is the money and where the money comes from.”

Sanders, who has an even more aggressive Medicare-for-all plan, got a skeptical reception from some Culinary workers in Las Vegas on Dec. 11.

As Democratic candidates leap into the presidential fray, many have latched onto a catchy political rallying cry: “Medicare for all.”

“We love our Culinary healthcare,” Elodia Muñoz, who went on strike for more than six years at the Frontier Hotel and Casino in the 1990s, told Sanders. “We want to keep it. I don’t want to change it. Why should I change it?”

“We have in this country a dysfunctional, broken and cruel healthcare system,” Sanders replied. But as he elaborated on his plan, chants from the audience interrupted, “Union healthcare! Union healthcare!” multiple times, drawing a rebuke from the union’s president. (“If you want to heckle, go outside to heckle,” Taylor told the chanters afterward.)

Sanders powered through and said his plan would result in higher wages for union workers, with employers no longer diverting dollars toward private health insurance programs with large or inefficient overheads.

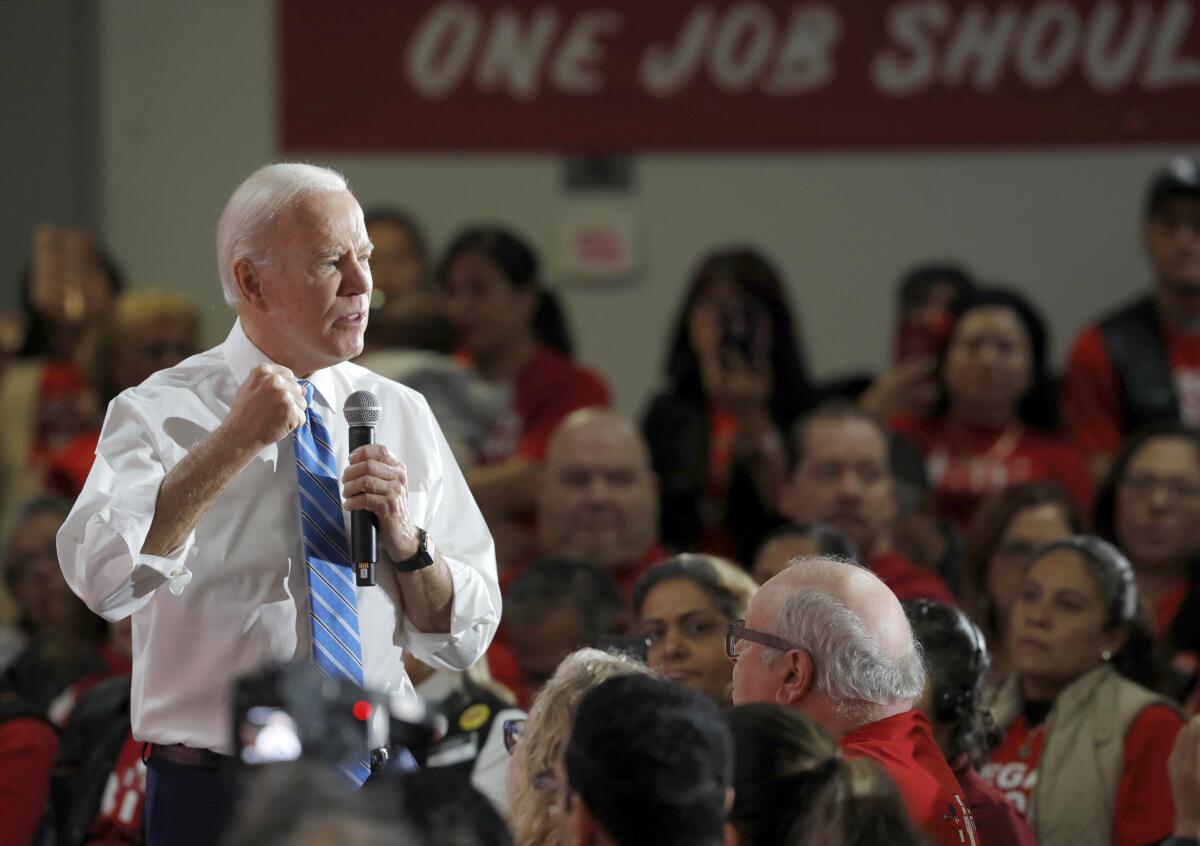

Former Vice President Joe Biden had a much easier time in his Dec. 11 appearance: He, like Mayor Pete Buttigieg of South Bend, Ind., favors a more moderate plan to create a public option that would not replace the Culinary Union’s insurance plan.

A hotel workers union in Boston offers members a plan with no deductible. Their case shows how costs can be kept in check and the trade-offs required.

“You’re gonna get to keep it with me,” Biden interrupted a cook from Margaritaville, who was winding up to ask Biden the same question every other candidate has gotten.

“Where I come from, I don’t like people telling me what I have to choose,” Biden said. Union members “who have busted their neck, walked on picket lines, gave up pay, took hits in order to get significant healthcare available, you get to keep it under my plan. You don’t have to give it up.”

Universal health insurance systems spread around the world after World War II, but not in the U.S., where private, employer-provided insurance flourished instead. This system has come under political strain in recent years as insurance costs have risen faster than wages, which has also forced many unions to fight losing battles against contracts that would increase healthcare costs for their members.

The Culinary Union has won and maintained its provisions through decades of strikes and bargaining. In 1984, 17,000 Culinary members from 32 Las Vegas Strip resorts went on strike for almost a year, a period during which 900 strikers were arrested. Another strike, at the Frontier Hotel and Casino, began in 1991 and lasted for more than six years.

Last year, employers under contract with Unite Here unions paid more than $1 billion in contributions into the union’s healthcare trust, compared with just $28.8 million from union members. Culinary Union workers don’t have premiums or deductibles, but they have certain copays and pharmaceutical costs, according to Culinary Union spokesperson Bethany Khan, who said the Culinary Health Center’s pharmacy fills about 20,000 prescriptions monthly.

In other words, the union in effect has its own private version of the single-payer system, with hotels and casinos, rather than the government, functioning as the single payer.

Although the Culinary Union is respected for its gains, labor activists who support Medicare for all still think universal governmental coverage would be more efficient, comprehensive and stable than such multi-employer plans, which are also offered by some other unions, including SAG-AFTRA and the Writers Guild of America.

“A lot of these funds, they cover precarious workers, construction workers, actors, people in film production, and they provide good benefits, but large numbers and large percentages of their members don’t qualify for their benefits because they don’t work enough hours,” said Mark Dudzic, coordinator of the Labor Campaign for Single Payer, a union coalition pushing for a Sanders-like Medicare-for-all plan.

Unions would also no longer have to bargain over whether employers’ dollars should go toward healthcare instead of wages or other benefits. “I think you could really construct much better advantages if you didn’t have to put all this money into basic healthcare,” Dudzic said.

In an interview Saturday, Sanders acknowledged that “there were a few people who objected” at his Culinary Union town hall but noted that he got a standing ovation at the end of the event.

“We have many unions who support Medicare for all, some who are reluctant,” Sanders said. But he thinks he can still make his case to union members by persuading them that under Medicare for all, “they’re not going to have to spend half of their negotiating sessions protecting the healthcare that they have, and they’re not going to have to give up wage increases in order to maintain or improve their healthcare benefits.”

Despite the Culinary Union’s reluctance on Medicare for all, Taylor, the Unite Here president, praised each of the Democrats who have passed through, and he made clear that he didn’t want it perceived that his union was fighting progressive changes on healthcare that would benefit less-fortunate workers.

“Just so we’re clear for all media, the healthcare system in this country has to change,” Taylor said during Warren’s event. “Healthcare should be a right and not a privilege, and no one should go without it.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.