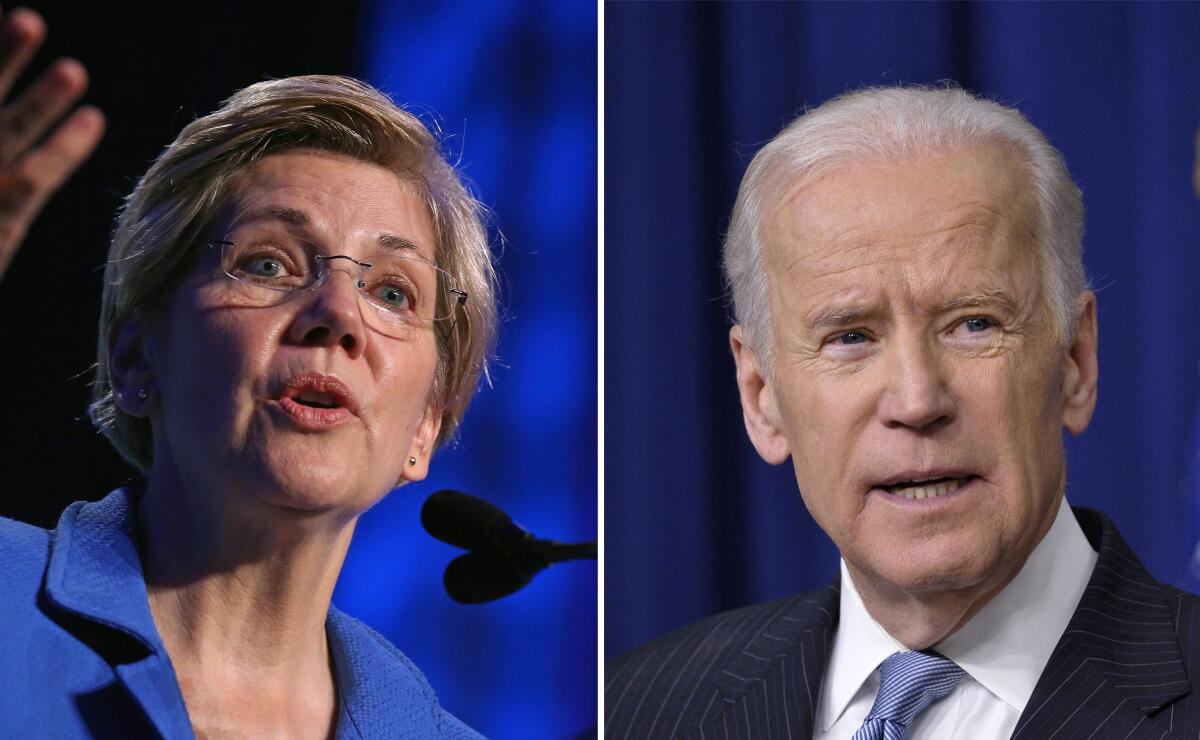

Four years ago, Joe Biden viewed Elizabeth Warren as a possible running mate; now they’re sparring

- Share via

WASHINGTON — As Vice President Joe Biden contemplated challenging Hillary Clinton for the Democratic nomination in August 2015, he scheduled an important, private Saturday lunch at his official residence.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren was the guest, and Biden had an audacious idea on his mind: He was eyeing Warren as a potential running mate, according to associates. The two met for more than an hour without any aides present.

Warren had spent more than a decade attacking Biden before she entered electoral politics in 2012, accusing him of selling out working-class people to help his home-state credit card industry when he was a U.S. senator from Delaware and she was a Harvard law professor with a specialty in bankruptcy.

But if Biden wanted to take on Clinton, who was likely to be the first woman nominated by a major party, many of his allies believed he needed to run with a woman and get the backing of the party’s progressive wing, which was mostly supporting Sen. Bernie Sanders of Vermont.

“It was the exploration of a ticket,” said one person close to Biden who was also in touch with Warren at the time and requested anonymity to discuss the sensitive deliberations. The Biden and Warren campaigns declined to discuss their candidates’ past communications.

Biden decided against running in 2016. So did Warren. When Biden decided not to run, he made a point of calling Warren to tell her of his decision, according to a person familiar with the call.

And when Clinton got the nomination, both seemed to have missed their shot at the White House.

But Donald Trump’s upset victory in 2016 reopened the path. Today, Biden and Warren are leading contenders for the Democratic nomination, fighting over the future of the party and, soon, for the first time, meeting on the same debate stage.

The Human Rights Campaign Foundation says the town hall marks the first time an LGBTQ-focused presidential event will be broadcast on a major network.

“They both faced these moments of truth in 2016 and for different reasons walked away,” said a former Obama administration official, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Here they are about to appear on the debate stage together, and just a few years ago, he was thinking, ‘Wouldn’t she be a good running mate?’”

As their 2015 lunch showed, the two have never broken off ties. While they remain divided on how far left to move the party, they have seen the practical benefits of remaining sometime allies.

A Warren aide, who declined to discuss private conversations on the record, said the two continued to talk by phone throughout the 2016 election as they watched Clinton run a losing campaign that devastated the party.

“Their differences are policy and not personal, and I think they both understand the enemy is Trump, not each other,” said former Rep. Barney Frank of Massachusetts, who worked closely with Warren to pass a law tightening regulation of Wall Street while Biden was vice president.

But those policy debates, especially over regulation of the credit industry, were so searing that they remain part of the DNA of their relationship. Warren and Biden, years later in public and private settings, repeatedly have brought up that confrontational chapter of their careers.

Biden once called Warren’s arguments “very compelling and mildly demagogic.” Warren, in a bestselling book, a New York Times op-ed and a law review article, cites Biden as an example of the Democratic establishment’s coziness with the credit card industry.

MBNA, the holding company that was once the world’s leading issuer of credit cards and later acquired by Bank of America, was based in Biden’s state.

Warren has not backed down from her criticism, which Biden’s allies call unfair and simplistic.

African American voters in Detroit are fired up to beat Trump. But they want some love from the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates.

The fight began in the late 1990s, when Warren, who had gained a national reputation as a pro-consumer expert on bankruptcy, began lobbying against a bill that she said unfairly penalized working people, particularly women, by making it harder for individuals to go to court to erase their debts.

Republicans supported the bill. Warren’s allies helped delay passage for nearly a decade, and many of them believe they could have held off longer if the Democratic Party had not been split.

“Joe Biden carried a lot of water for that bill,” said Jason Spitalnick, a former law student of Warren’s who helped her maintain a blog that she used to lobby against the bill. “The things he said about the bill were the things we had to counter.”

Warren decried the “halo effect” Biden received from women’s groups for leading the fight to pass and renew the Violence Against Women Act.

“Senator Biden’s support of legislation that helps women and his even more vigorous support of legislation that hurts women poses a serious question: what constitutes a women’s issue?” she wrote in the Harvard Women’s Law Journal in 2002.

She followed up a year later in her book “The Two-Income Trap.”

“Senators like Joe Biden should not be allowed to sell out women in the morning and be heralded as their friend in the evening,” she and her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi, wrote.

Biden said in a 2005 Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that he had delayed passage of the bill at one point to add protections for women, including one that prioritized paying off child support and alimony obligations. He argued that Warren was unfairly trying to hold creditors responsible for other societal problems that stress poor families, including the high cost of healthcare. He said Warren’s real problem was usurious credit card interest rates, not the bankruptcy bill.

The debate at the hearing grew heated at times, with Warren, speaking from the witness table, beating back each argument from Biden, a former chairman of the committee, and even correcting him on a factual error involving the Delaware court system. She said the credit card companies had already “squeezed enough out of these families in interest and fees and payments.”

“If you’re not going to fix that problem, you can’t take away the last shred of protection for these families,” Warren pleaded.

Biden raised his voice and grew exasperated at times — accusing Warren of looking for “boogeymen.” But he drew a laugh from Warren and the rest of the audience by concluding his exchange with a grin and a compliment:

“You’re good, professor.”

Warren wasn’t good enough to stop the bill. It was signed into law in 2005 and ended up having its desired effect, curtailing the number of bankruptcies. According to later research, it pushed more families into insolvency.

Biden’s aides now say that he believed at the time that passage of the bankruptcy bill was inevitable in a GOP-controlled Senate and was working to improve it as much as possible.

Jared Bernstein, who later served as Biden’s chief economic advisor in the White House, says Warren was proved right on policy, even as Biden scored a legislative victory. But he says Biden came around to sharing many of Warren’s economic views when he came to the White House and helped President Obama combat the housing crisis and the Great Recession.

“I don’t remember him expressing regrets about the bill itself,” Bernstein said. “I remember him talking about — it’s a different thing to be the vice president of a country and a senator from Delaware.”

“Let’s not play ‘gotcha’ here,” Bernstein added. “I think what’s impressive about Biden is how much his views evolved on financial regulation. And, in that regard, he was influenced by Warren’s thinking.”

The fight demonstrated an unyielding streak in Warren that could cause trouble in wooing swing voters looking for a president who is more centrist or willing to compromise. Later, in the Obama years, even fellow Democrats were sometimes riled by her rigidity, as when she blocked nominations for key posts because of nominees’ Wall Street ties.

She also has other economic ideas that put her to the left of Biden, including a plan for a wealth tax and support for the elimination of private health insurance.

Warren’s allies say the bankruptcy bill, while not the only standard by which to judge Biden, was something she marked down as an important moment. As recently as April, she faulted Biden for standing “on the side of the credit card companies” when “the biggest financial institutions in this country were trying to put the squeeze” on struggling families.

Yet at other times, she has praised Biden for his magnanimity in victory. She once described an occasion when they ran into each other in the White House, when Warren was working on financial regulations in 2010 or 2011:

“There she is,” Biden shouted from a distance, according to Warren’s recollection. “There’s the woman who cleaned my clock.”

Biden made another joke about their storied fight in 2013, when he ceremonially swore Warren into the Senate after her 2012 election. He hugged Warren and her husband, Bruce Mann, and told them that it was the first time he was happy to see her.

Of their previous encounter, he said, “You gave me hell.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.