News Analysis: Debate highlights Democrats’ diversity, but also their fraught divisions on race

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Sandwiched between a heated but often disjointed argument over healthcare and an inconclusive discussion of climate change, 10 Democratic candidates for president grappled Wednesday evening with race — their party’s greatest potential source of strength and also its most fraught division.

Never in the history of major-party presidential debates has so diverse a group of candidates appeared on a presidential debate stage: three women and five people of color, including a Latino former Cabinet member and two black U.S. senators.

That lineup showed the face of the Democrats’ multiracial and multiethnic coalition, which provides a central advantage for the party in a country whose nonwhite population is rapidly growing, especially in the metropolitan areas where most Democrats live.

In the 2016 election, only 1 in 10 of Donald Trump’s voters were nonwhite, according to a study by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center. By contrast, 4 in 10 of Hillary Clinton’s voters were people of color. About 2 in 10 Clinton voters were black; only about 1 in 50 Trump voters were.

But as Wednesday’s debate showed when it turned to issues of criminal justice, school segregation and immigration, multiracial coalitions can be fractious. That’s especially true when the incumbent president has elevated racial conflict to the top of the agenda by persistently playing on the country’s divisions.

For the second consecutive debate, it was the leader in the polls, former Vice President Joe Biden, who took most of the incoming fire on those issues. As a 76-year-old white man seeking to lead a diverse party, and as a politician with nearly half a century of positions to defend — many of which are out of step with today’s Democrats — Biden provides rivals with extensive material for attacks.

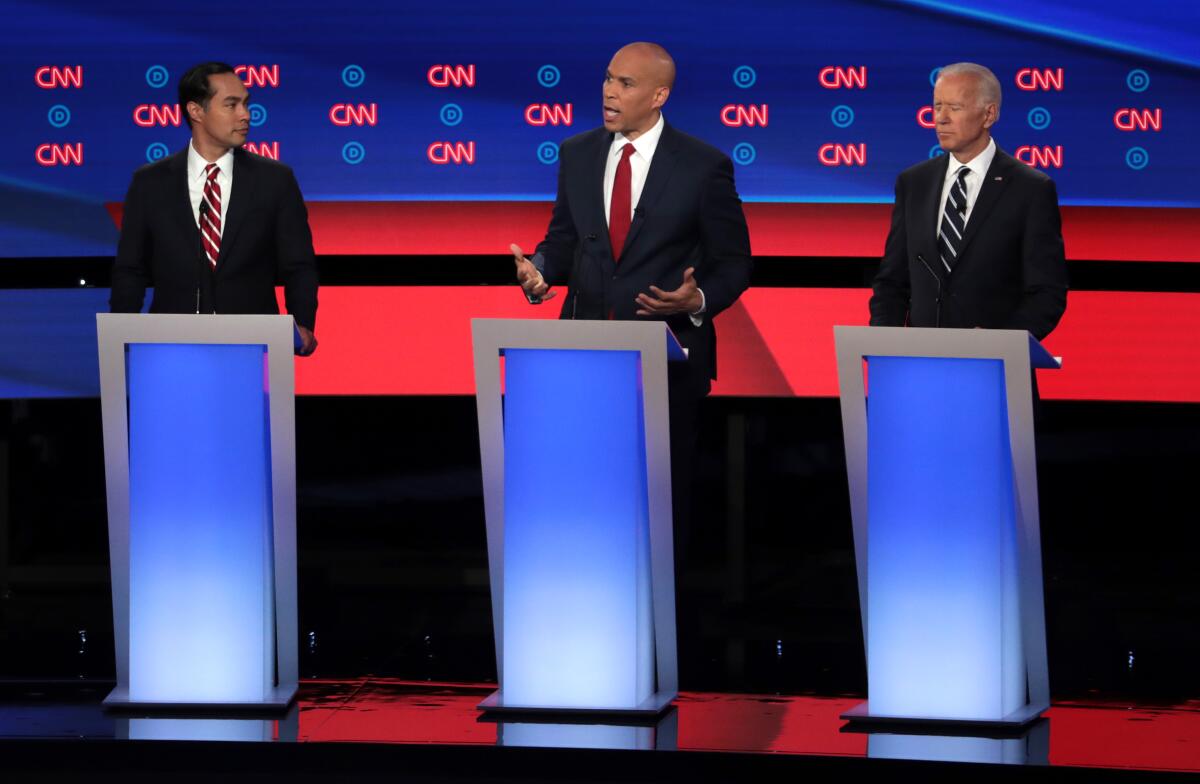

Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey launched an early salvo, going after Biden’s record of anti-crime legislation in the 1980s and 1990s that critics say contributed to the mass incarceration of minorities, especially black men.

“Mr. Vice President has said since the 1970s that every single crime bill, major and minor, has had his name on it. The house was set on fire and you claimed responsibility. You can’t just now come out with a plan to put out that fire” and expect people to consider that enough, Booker said to Biden, who stood next to him.

Attacks on Joe Biden were unrelenting in a contentious Democratic debate Wednesday night in Detroit.

Sen. Kamala Harris of California, who stood on Biden’s other side, reprised the attack she launched in June’s debate on Biden’s willingness to work with segregationist senators early in his career.

“Had those segregationists had their way, I would not be a member of the United States Senate. Cory Booker would not be a member of the United States Senate. And Barack Obama would have not been in the position to nominate him to the title he now holds,” she said, gesturing toward Biden.

Biden shot back in both cases, accusing Booker of failing to curb allegedly discriminatory stop-and-frisk policies by his city’s police force when he was mayor of Newark, N.J., and charging Harris with failing to act against school segregation in California as that state’s attorney general.

Those exchanges pointed up racial grievances that have the potential to divide Democrats. A few minutes later, New York Mayor Bill de Blasio reopened an issue that has alienated some Latino voters from the party — the high number of deportations during Obama’s first term.

De Blasio demanded to know whether Biden had counseled Obama to pursue different policies — a question Biden refused to answer.

The June debate itself does not appear to have eroded Biden’s support in any significant, long-term way, polls indicate, although his lead has shrunk since he first declared himself a candidate this spring.

For Democrats, the larger problem could be one of collateral damage. Diversity provides a source of strength for Democrats when they can hold together a multiracial coalition.

Obama did that in his two campaigns for president, in which he largely downplayed racial issues. In 2012, when he won reelection, he succeeded in generating record turnout among African Americans while still winning large numbers of white, working-class voters in key states of the northern Midwest and the Industrial Belt.

Two-thirds of eligible black voters turned out that year. It was the first time in U.S. history that African Americans turned out at a higher rate than whites.

Joe Biden and Kamala Harris came under attack on the second night of Democratic debates in Detroit on Wednesday.

By contrast, in 2016, when Hillary Clinton lost to President Trump, she suffered erosion from both parts of that coalition: She lost significant numbers of working-class whites who had voted for Obama. At the same time, black voter turnout dropped for the first time in 20 years, with about 765,000 fewer African Americans voting than had done so four years earlier.

Clinton likely would have won both Michigan and Wisconsin had black turnout stayed at 2012 levels, although those two states alone would not have given her enough more electoral votes to send her to the White House.

Many things went wrong for Democrats in that defeat, but one important factor was that the Trump campaign capitalized on doubts in the minds of many black voters, particularly younger ones, about Clinton’s record in the 1990s, when she supported many of the same anti-crime policies that Biden had championed.

Many of those issues also surfaced during the sometimes bitter 2016 primary race between Clinton and Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.).

Trump has made clear that he intends to continue to crank up racial tensions. Democrats, to gain maximum advantage from their multiracial coalition, will likely want to emulate Obama and try to calm them. As Wednesday’s debate showed, the inevitable tensions of the primary campaign are not making that task any easier.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.