As power of California Senate leader grows, so does her spouse’s consulting business

- Share via

Reporting from Sacramento — Toni Atkins is one of California’s most powerful lawmakers, ascending to leadership roles in the Assembly and Senate the last five years.

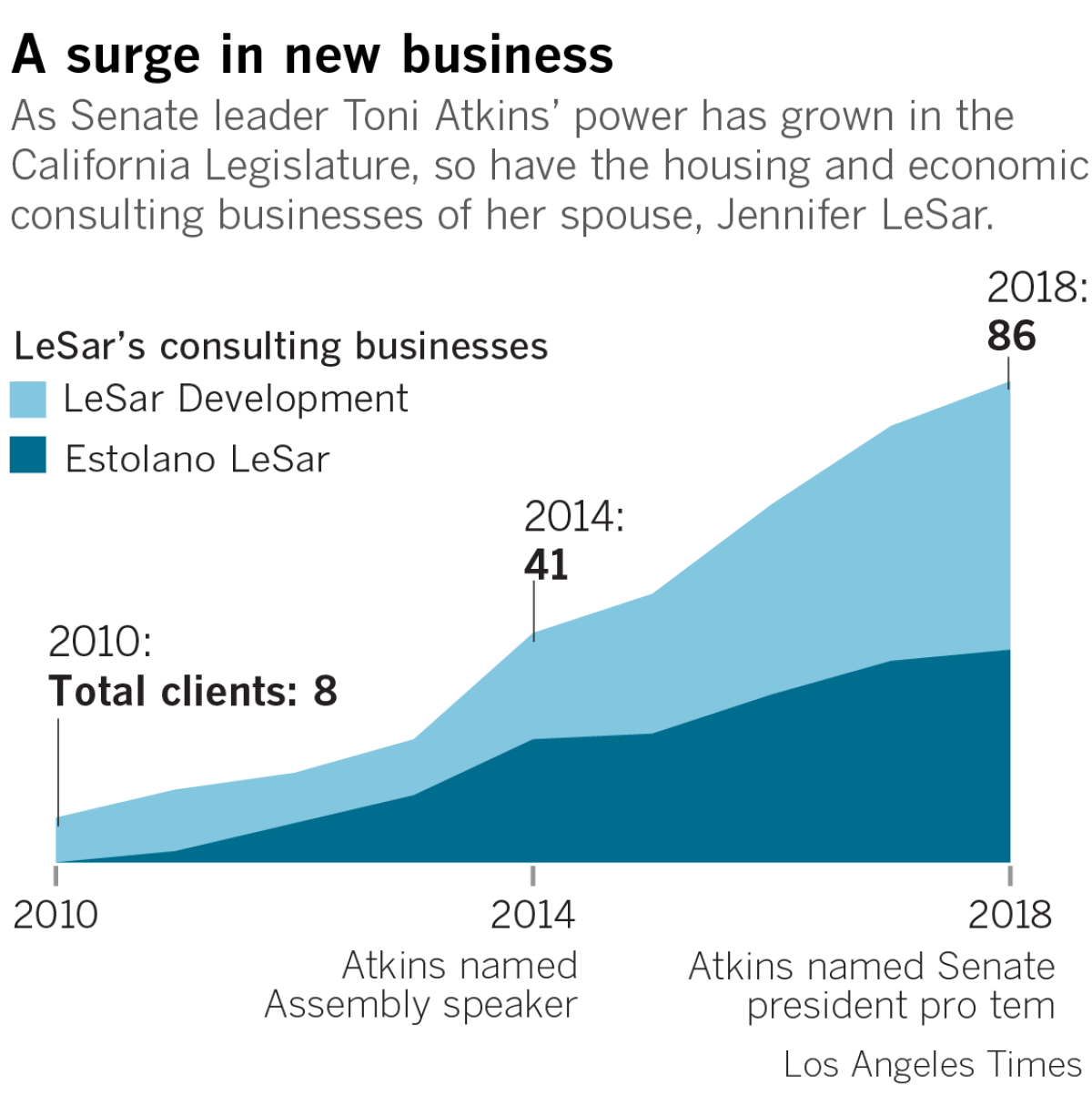

As Atkins’ clout has soared, so too has the consulting businesses of her spouse, Jennifer LeSar.

The clientele for LeSar’s two affordable housing and economic development firms has grown nearly fourfold since 2013, the year before Atkins became Assembly speaker, according to Atkins’ economic disclosure forms.

In 2018, the year that Atkins’ colleagues elevated her to Senate president pro tem, her spouse’s firms had contracts with 86 public agencies, developers, nonprofits and other clients, the forms indicate, which was more than in any previous year. The year before, LeSar had received a lucrative contract from a Bay Area agency without going through a competitive bidding process — a rare step allowed in emergencies, when a company offers a unique service or when the agency can justify a compelling reason to do so.

LeSar is now in a position to potentially garner even more business as Gov. Gavin Newsom and legislative leaders, including her spouse, propose increasingly bold responses to the state’s housing affordability crisis.

In the last three years, LeSar’s firms have received $1.3 million from state agencies alone, including contracts to implement one of the state’s largest low-income housing programs, which Atkins, a Democrat from San Diego, supports. Additionally, over the last 18 months, LeSar worked on a plan that calls for a package of state legislation that would rewrite major California housing policies. The Metropolitan Transportation Commission, a Bay Area public agency, is paying LeSar’s firm more than half a million dollars for the effort, through the no-bid contract.

Agency executives said LeSar’s relationship with Atkins had no bearing on their decision to hire her, and the Senate leader said she wouldn’t treat the bills any differently than any other proposals from her colleagues.

Atkins and LeSar, who has worked in affordable housing for nearly three decades, both said they are concerned about a perception of conflicts of interest and, as a result, consult with attorneys about possible intersections in their work.

“We spend a lot of time trying to make sure in our very busy days that we’re following the letter of the law,” Atkins said.

“These questions have been asked and answered before by the press and have largely been accepted as a nonissue,” LeSar said in an email response to The Times. She declined an interview request.

Rey Lopez-Calderon, executive director of the government ethics group California Common Cause, said the dramatic increase in LeSar’s clientele could raise concerns from the public that outside groups are trying to curry favor with a powerful politician by hiring her spouse.

“That’s really obviously a number that’s eyebrow raising,” Lopez-Calderon said. “It definitely runs the risk of the public thinking something shady is going on.”

Still, he said, absent evidence LeSar or Atkins used their relationship to leverage new business, there wasn’t anything illegal or unethical about LeSar’s consulting work.

Lawmakers have faced questions about potential conflicts involving a spouse and development issues before. In 2011, opponents of redevelopment agencies, which provided significant funding for low-income housing, criticized then-state Sen. Bob Huff about his efforts to save the program, noting that Huff’s wife was a paid consultant for a developer with a financial stake in the issue.

Political rivals have alleged Atkins’ relationship with LeSar is also a conflict, given Atkins’ outsized role in housing debates. In 2015, Atkins, then in the Assembly, proposed legislation to impose a fee on real estate transactions, such as mortgage refinancing, to fund low-income housing development. A version of the bill passed in 2017. When she first introduced the measure, Atkins requested an opinion from the Office of Legislative Counsel, which assured her that the bill presented no conflict of interest because the funding was not tied to any specific company or project. LeSar has vowed not to bid on funding directly tied to the bill.

Assembly leader Toni Atkins denies conflict of interest in funds proposal »

The couple married in 2008 after meeting while running in housing, LGBT advocacy and political circles in San Diego, where Atkins once served as a city councilwoman. Just before her election to the Legislature, Atkins worked for LeSar Development for about 18 months. While there, she wrote a report on development near transit and handled other housing work across the state. As of last month, Atkins was pictured on the business’ website, listed as an alumna of the firm. She no longer appears on a redesign of the site that became public Wednesday.

In 2011, after Atkins had been elected to the Legislature, LeSar opened a second firm, Estolano LeSar Advisors, with Cecilia Estolano, an attorney who worked in housing and economic development for the city of Los Angeles. Last year, Atkins abstained from voting on Estolano’s appointment to the powerful UC Board of Regents, which governs the state’s flagship university system.

Recent clients for the two firms, according to Atkins’ economic disclosures, have included the city and county of Los Angeles, UC Berkeley, USC, the California Endowment, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California, for-profit and nonprofit developers and the Open Society Foundations, the organization founded by billionaire George Soros.

Rick Gentry, president of the San Diego Housing Commission, praised LeSar. Among other work, he said, she guided his public housing agency in 2014 into expanding its portfolio to provide homelessness services.

“She knows as much about the industry as anyone I’ve ever met,” Gentry said.

Officials with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission cited LeSar’s experience as their reason for hiring her.

The agency was finishing an effort to plan for growth in the Bay Area through 2040 and realized that project was futile without a comprehensive attempt to deal with the nation’s worst housing affordability challenges.

“Jennifer LeSar is extremely qualified and well-positioned to take on multiple roles for this project,” wrote Vikrant Sood, a senior planner with the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, in a June 2017 memo justifying her hiring.

LeSar’s firm researched prior studies on the region’s housing problems and planned and attended the group’s meetings. The result of the effort was a proposal, known as the CASA Compact, which said the Bay Area could fix its housing problems only through a suite of state legislation.

The CASA Compact calls for new state laws to boost protections for tenants, increase apartment construction near transit and help raise more than $1 billion to build low-income housing, among other things. Bay Area legislators have introduced more than a dozen bills that align with the plan, nearly all of it affecting the entire state.

Metropolitan Transportation Commission officials said LeSar did not recommend any of the policies the region decided to pursue but, rather, packaged together the conclusions into a final report. LeSar also said she declined additional work with MTC once it became clear that the CASA Compact was going to advance state bills.

She said she sought a legal opinion in January after the agency discussed offering her a new contract to help implement the plan.

LeSar initially told The Times that her attorney had advised her that the second contract would be a potential conflict so she declined the work. But in later correspondence with The Times, she said that she had been mistaken. The attorney’s advice, LeSar said, was that the new contract wouldn’t pose a conflict, but she decided to forgo the work to avoid any appearance of a problem.

Commission officials anticipated the CASA Compact process would lead to state legislation from the beginning. Sood said in the June 2017 memo that originally justified LeSar’s hiring that CASA “will yield a package of legislative and funding solutions at the state and regional level.”

Despite that, agency officials decided to pursue LeSar directly rather than putting the initial contract out to a competitive bid, a process designed to ensure an agency receives the best services for the lowest cost and without bias. The agency said it could do so because it had a compelling reason — LeSar’s background and the ambitious nature of the project — to hire her without first seeking out other firms.

No MTC officers publicly opposed hiring LeSar. Following agency rules, then-Executive Director Steve Heminger signed off on the first $200,000 of the contract himself. The agency’s administrative committee, which is made up of Bay Area elected officials, voted unanimously and without comment in December 2017 to increase the amount to $450,000. (The contract value rose to $511,000 when it was extended again at the beginning of this year.)

Some local government officials in the Bay Area’s smaller cities oppose the CASA Compact because they believe it takes away their power. Michael Barnes, a councilman in the city of Albany — a community that borders Berkeley — said LeSar’s extensive work with the MTC over the last 18 months adds to fears that lawmakers, out of deference to Atkins, will overlook local leaders’ concerns when evaluating the legislation.

“We have very strict guidelines for our ethical behavior,” Barnes said. “For me, as someone who has lived under these guidelines as an elected official, this doesn’t seem ethical.”

LeSar’s businesses also have seen an increase in contracts with state agencies, per Atkins’ economic disclosures. Since February 2016, the two firms have received at least nine contracts from four state departments. All but one — a $5,000 contract to advise housing department employees on evaluating loan documents — were awarded through competitive bidding processes.

Much of the contract work has come from the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research, which is responsible for administering housing and planning efforts funded by the state’s cap-and-trade program, which taxes polluters. The state has provided roughly $400 million annually through Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities program, one of the largest budget allocations for low-income development and one that Atkins has said she “led the effort” in the Legislature to fund. Estolano LeSar was hired to help applicants from disadvantaged communities write grants and provide other support for their projects.

Newsom’s office declined to comment, but Ken Alex, who was OPR director under former Gov. Jerry Brown, said he was unaware of Atkins and LeSar’s relationship.

“I have heard from staff that the work was good and would have been advised if it was not,” Alex said.

Atkins said she has sometimes voted in ways that have hurt her spouse’s business. In 2011, she supported ending the state’s redevelopment program, the property tax set aside for local governments that funded local affordable housing and economic development.

“I was part of a vote that actually almost killed her business for a period of time,” Atkins said.

Atkins said she doesn’t plan to write any of the bills recommended in the CASA Compact proposal. She said she wouldn’t abstain from voting on them or otherwise handle them differently than any other piece of legislation because the bills address broad policy matters and therefore don’t present a conflict.

But if CASA Compact measures pass, it could be a signal to outside groups that hiring LeSar could be beneficial to getting similar efforts through the Legislature, given Atkins’ substantial influence over the fate of legislation at the Capitol, said Lopez-Calderon of Common Cause.

“I definitely think that some businesses will imagine that exact scenario and act accordingly,” he said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.