On Politics: He struck out at baseball, but made it big in politics. Now he’s returned to his first love

- Share via

Reporting from San Francisco — When Ace Smith was a boy he dreamed, like many, of growing up to be a Major League Baseball player. A power-hitting catcher, to be precise.

As he grew older, though, he came to understand, like most boys, he wasn’t talented enough to realize his dream. So he pursued another career, which proved highly successful.

Smith’s passion for baseball remained undimmed, however. So in between helping elect Kamala Harris to the U.S. Senate and Jerry Brown as California governor and Gavin Newsom as lieutenant governor, he returned to his first love, chronicling a strange and obscure slice of baseball history.

In 1937, a group of standouts from the Negro baseball league, as it was known, was lured to the Dominican Republic for a barnstorming tournament against the country’s home-grown talent. Soon enough, the sun-and-fun adventure became a life-and-death proposition; the competition, it turned out, was for the benefit of the homicidal dictator Rafael Trujillo. The instruction given the visiting all-stars was simple: “You better win.”

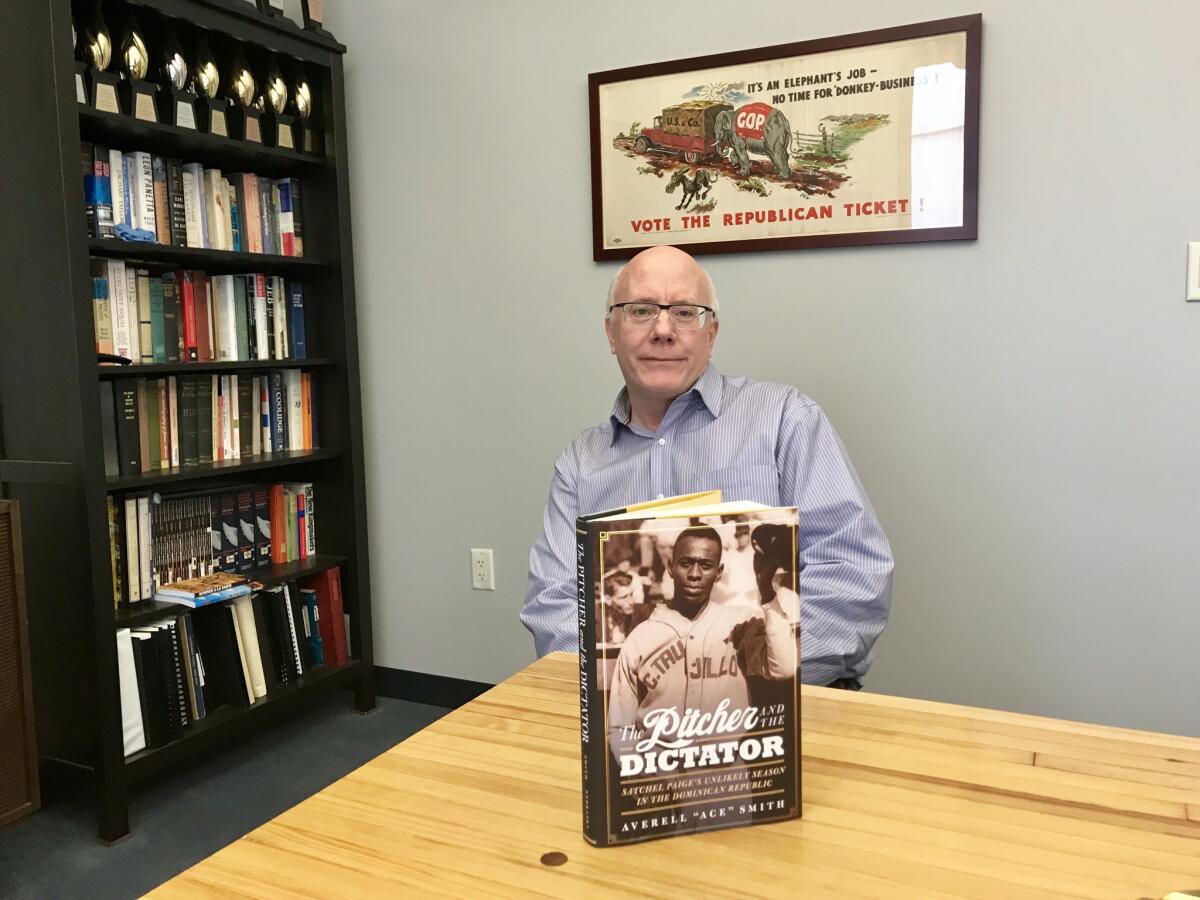

While baseball is at the heart of the book, “The Pitcher and the Dictator” — the pitcher being the legendary Satchel Paige — the story is about much more, including gunboat diplomacy, the blood-drenched history of the Dominican Republic and, not least, the prevalence of racism and repression in mid-20th century America.

“One of the great ironies,” Smith said in an interview, is the visiting black players were “coming from the land of the free, home of the brave, and they’re going into one of the most repressive dictatorships in the world. Yet in some sense they have more freedom in that repressive dictatorship than they do in the United States.”

In the book he explains, “Satchel and his friends had been able to eat, drink, carouse, and sleep anywhere they wanted” — things blacks couldn’t do back home in many places.

That said, the visiting stars had a bit too good a time, diminishing their on-field performance and resulting in the head of the government’s death squad being attached to their team’s management. Trujillo, who plastered his name on mountains and cities and all manner of self-referential adornments, was not one for subtlety.

Smith, however, is.

At 59, balding, gray-haired and bespectacled, he has the mien of an accountant, or some other bland pencil-pusher, which belies a quiet political lethality.

He first gained renown — in political circles, anyway — as a master of opposition research, one of the so-called dark arts of political campaigning. Burrowing in libraries and pawing through yellowed documents, the practice is intended to turn up the lethal nugget — a tax lien, messy divorce, politically inconvenient vote, long-hidden trespass — that can kill a candidacy.

All that excavation turned out to be excellent training for the years Smith spent poring through microfiche to reconstruct the depredations of the Jim Crow South — one particularly harrowing chapter involves a lynch mob in New Orleans — and diving into Dominican government archives to capture the roar of fanaticos in the stands of the Campo Deportivo Municipal.

“The ninety-degree angled colonial white structure shot straight up three layers like a wedding cake,” Smith writes. “The dugouts along each foul line were like giant open bread boxes.”

The book was conceived, Smith said, as he was coming off Antonio Villaraigosa’s successful campaign in 2005 for Los Angeles mayor. (Smith is now advising Newsom in his gubernatorial bid against Villaraigosa and others.)

An avid reader, who said he can polish off 100 or so books a year, Smith had just finished Mario Vargas Llosa’s “The Feast Of The Goat,” a brilliant novel based on the 1961 assassination of Trujillo, when he came across an account of Paige’s brief sojourn in the Dominican Republic. A lifelong fan of the Negro leagues, Smith instinctively began digging deeper.

“I’ll never stop,” he said, “until I have every thread that I grabbed completely pulled out.”

It took more than a decade of research, travel to the Caribbean and four drafts to finish the book, with Smith writing most mornings between 4 and 8 o’clock before returning to his day job running campaigns. (He set aside the project for several years after his 15-year-old daughter, Lili, died in her sleep in 2009. The book is dedicated to her memory.)

His work complete, Smith professed to have modest expectations. “I did it for fun,” he said over ravioli at a favorite trattoria in San Francisco’s Financial District.

But in the book’s preface, along with the thank-yous and a short paean to Satchel Paige, he expressed a grander, more politically minded ambition. “I can only hope,” Smith wrote, “that my little book opens more eyes to the mighty and heroic struggles of African Americans in the United States.”

Publication is set for April 1.

@markzbarabak on Twitter

ALSO

Why the rise of the independent voter is a political myth

San Francisco’s next mayor will be a political star in California. Who will it be?

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.