Duf Sundheim resists the moderate label

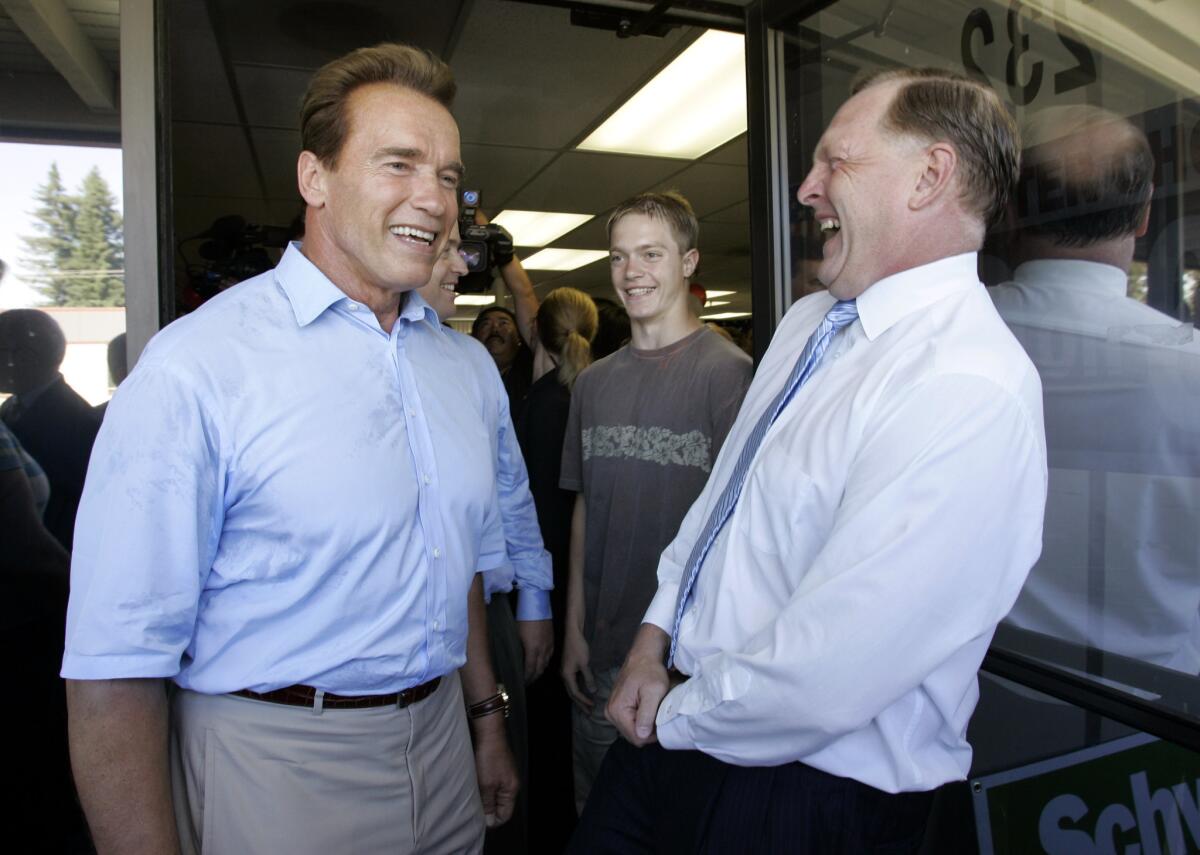

Former California Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, left, smiles with Duf Sundheim, right, former chairman of the California Republican Party, at Schwarzenegger’s campaign office in Mountain View, Calif. on July 13, 2006.

- Share via

Senate hopeful George “Duf” Sundheim hand-built a successful law practice and rose to the pinnacle of California’s Republican Party. His leadership of the GOP is a defining element of his candidacy in the race to replace U.S. Sen. Barbara Boxer.

Sundheim’s political universe consists of business leaders and conservative thinkers such as former U.S. Secretary of State George P. Shultz, and his message has the distinct echo of Reagan-era views on national security and a more progressive stance on gay rights, immigration and climate change.

He headed the California Republican Party at the dawn of a dark, turbulent era for the GOP as it struggled to stem the steady loss of voters. The decline has been hastened by the party’s divide with Latinos, which began in earnest with the hard-line, anti-immigrant fervor unleashed by Gov. Pete Wilson and other Republican leaders in the 1990s.

A glimmer of hope for a Republican revival came in 2003, when Sundheim led the state party, with the recall of Democratic Gov. Gray Davis and the election of Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger.

But even with the help of a Hollywood action hero, efforts by Sundheim to broaden the party’s base failed to brighten its fortunes. A GOP candidate hasn’t been elected to statewide office in a decade, and the vast majority of Latinos, who now outnumber whites in California, continue to shun the Republican Party.

Sundheim was born in 1952 and grew up outside Chicago. He was named after his father, George M. Sundheim III, a successful business attorney and former linebacker on Northwestern’s 1949 Rose Bowl championship football team. He picked up his nickname while still in his mother’s womb as his father would pat her belly and ask, “How’s the little duff doing?” Sundheim says.

Sundheim was a football and drama star at Lyons Township High School, where he played quarterback and once shared the stage with David Hasselhoff in their school’s production of “The Fantasticks.”

All that fame in high school probably would have gone to his head, Sundheim says, were it not for seeing the cold realities of life that his mentally-challenged brother, David, faced every day. Sundheim recalls his teenage friends chiding him as too somber and serious.

“That’s because I would come home to a mom who was terrified that her son would be institutionalized,” he said.

David became the “center of my entire family,” at a time when people with mental disabilities were often treated as outcasts, Sundheim says. He often tears up on the campaign trail when he speaks about David, who died in December.

Sundheim played quarterback at Stanford University in the 1970s, but was hobbled by injuries and saw limited playing time. He has a habit of slipping in football analogies during casual conversations.

Sundheim followed his father into the legal profession and eventually starting a lucrative law practice specializing in intellectual property rights in Silicon Valley.

Being immersed in that high-tech world has changed Sundheim’s perspective on some of the most pressing issues facing the nation. He believes technology should be used to secure the U.S.-Mexico border rather than building a wall. He acknowledges climate change is a real phenomenon, but would emphasize the use of technology to reduce man-made pollution, not regulations.

“The right way to go about it is to encourage innovation,” Sundheim says.

He also runs counter to the Republican orthodoxy with support for abortion rights, same-sex marriage and a “pathway to legal status” for undocumented immigrants.

On the campaign trail, Sundheim is just as likely to quote Presidents Kennedy and Franklin Delano Roosevelt as he is Reagan. He rips President Obama for his nuclear deal with Iran, but also has praised Gov. Jerry Brown for doing a “job good” repairing the state’s fiscal mess.

Still, he bristles when labeled a “moderate.”

“I’m not a moderate,” Sundheim said. “I’m a reformer who gets things done.”

California Republicans elected Sundheim as the party chairman in 2003, an upset given that he was not aligned with the GOP’s conservative wing or a member of the party leadership.

The top contender for the post, state GOP Vice Chairman Bill Back, had dismissed Sundheim as “a member of the country club Republicans who write checks.”

Sundheim initially opposed the Republican effort to recall Davis, thinking the state party’s top priority should be the reelection of President George W. Bush.

“Then I got in there and I studied it. The deficit was going through the roof, taxes were going through the roof. We had the energy crisis,” he says.

Sundheim now boasts about the Schwarzenegger era, the four Republicans who were elected to statewide office and the tens of millions the party raised during his two terms.

Sean Walsh, a senior policy advisor to Schwarzenegger, said Sundheim won over Republican donors who had fled the party after the disastrous gubernatorial campaign of conservative Dan Lungren, and became a Schwarzenegger ally.

Sundheim’s allegiance to Schwarzenegger, a polarizing figure within the GOP who in 2007 blasted his party for “dying at the box office,” caused friction.

In 2005, Sundheim signed off on a $3-million loan to the party from Larry Dodge of Orange County, founder of the banking and insurance firm American Sterling, to help keep the party afloat during Schwarzenegger’s reelection campaign.

Schwarzenegger “supposedly gave assurance to Duf that he would help pay it back, and Duf was stupid enough to believe him,” said Michael Schroeder, who served as party chairman in the 1990s and has endorsed Tom Del Beccaro.

After Sundheim’s term as chairman ended, Dodge tried using the unpaid loan as leverage. In 2008 he sent a letter to the new state GOP chairman criticizing the party for alienating moderates and independents.

The controversy grew when Sundheim accepted a job as executive director of the California Republicans Aligned for Tomorrow. Dodge was chairman of the new political organization, funded by wealthy GOP moderates seeking to stock a “farm team” of candidates to put their party back in power.

Sundheim says the group was instrumental in recruiting former eBay Chief Executive Meg Whitman to run for governor in 2010 and former Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. Steve Cooley to run for state attorney general that same year. While both candidates lost, they were credible challengers, he says.

Sundheim eventually persuaded Dodge to forgive his $3-million loan to the party.

Sundheim trails far behind the top two Democrats in the Senate race, Atty. Gen. Kamala D. Harris and Rep. Loretta Sanchez of Orange, in both recent opinion polls and campaign fundraising. And with less than $100,000 in cash on hand at the end of March, neither Sundheim nor Del Beccaro, who once led the state GOP, has the financial wherewithal for a statewide political ad campaign to lift their profile in a state as massive as California.

Each is hoping to pull off a second-place finish in the June 7 primary and advance to the general election. The ballot for California’s U.S. Senate race is overflowing with 34 candidates, including 12 Republicans, which threatens to splinter the vote.

“Both understand the math of the situation,” said Bill Whalen, a fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution who was a speechwriter for former Republican Gov. Pete Wilson. “I think what you have here are two people who know a lot about California politics but have very different views on what ails the Republican Party.”

ALSO:

Tom Del Beccaro is forging his own version of the California GOP

California’s next senator could be a Latina. Will her past mistakes get in the way?

How race helped shape the politics of Senate candidate Kamala Harris

Controversial English-only crusader sets his sights on California’s Senate race

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.