The economy is thriving — but that may not be enough to get Trump reelected

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — After a sluggish start this year that had sparked fears of recession, the American economy has taken a sweeping turn for the better: Consumer spending has picked up, stocks are back at record levels, and the outlook for trade has brightened along with the global economy.

Confirmation of the good news came Friday with the latest monthly jobs numbers, showing the economy produced 263,000 new jobs last month, average wages rose at a solid pace, and the nation’s unemployment rate fell to 3.6%. That’s the lowest in almost 50 years.

The news bolstered President Trump, for whom a strong economy provides a necessary — but perhaps not sufficient — basis for reelection. Trump cheered the report, declaring in a Twitter message: “JOBS, JOBS, JOBS!”

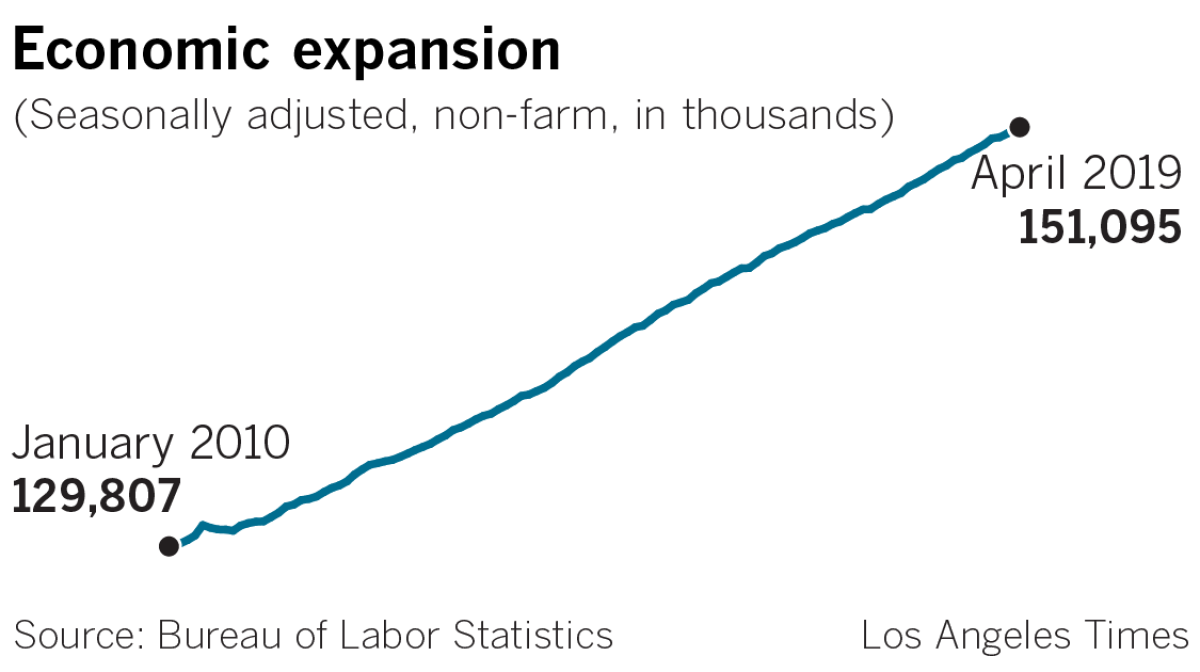

The number of jobs in the economy has now grown for 103 months — a record — at a remarkably steady rate through two very different presidencies.

All that deepens two of the great conundrums of the Trump presidency: How does his approval rating stay so bad when the economy is so good, and what might that forecast about his prospects for reelection?

“When we have an economy that maybe is the best economy we’ve ever had, people tend to like you,” Trump said Friday during a meeting with the visiting prime minister of Slovakia.

Indeed, “a normal president with these economic numbers would have job approval somewhere in the vicinity of 60%,” said Republican pollster Whit Ayres. “But Donald Trump is a nontraditional president, and he has, at least at this point, severed the traditional relationship between economic well-being and presidential job approval.”

Currently, an average of just over 4 in 10 Americans approve of Trump’s performance in office, a number that has fluctuated in a very narrow range since early in his presidency.

“That said, a good economy obviously helps a president running for reelection,” Ayres said. “We have to see if it helps Donald Trump as much as it would have helped a traditional president.”

At least since the end of World War II, economic growth rates have lined up strongly with the vote share received by the president’s party.

Two factors appear to have held down Trump’s ability to benefit as much as his predecessors might have: his personal conduct and the nature of the current economy.

A large share of American voters find Trump repugnant, and for them, no amount of good economic news will change their view. They’re numerous enough to make a close election in 2020 highly likely.

Beyond that, the uneven nature of current prosperity gives Democrats an opening to argue for spreading the wealth more equitably.

“The moral obligation of our time is to rebuild the middle class. When the middle class does well, everyone does well,” former Vice President Joe Biden, the current Democratic front-runner, told audiences in Iowa this week. Regardless of whom the Democrats nominate, the candidate likely will use some form of that argument.

It’s a case that finds a receptive audience among many voters. A recent Washington Post/ABC poll found that by nearly 2 to 1, Americans said “the economic system in this country mainly works to benefit those in power,” rather than “all people.” Democrats overwhelmingly took that view, but so did about a third of Republicans, the poll found.

Still, Trump had been noticeably worried in the fall and earlier this year by the talk among economic forecasters about a rising risk of recession, and those worries dissipating has been a great relief to the White House.

“Viewed from today’s perspective, the beginning of the year seems like just a bad dream,” said Carl Tannenbaum, chief economist for Northern Trust in Chicago.

Earlier in the year, Tannenbaum had put the odds of recession in 2019 at 33%. He’s since lowered that to less than 20%, and even that is partly because of statistical reasons.

The last recession ended in June 2009, making the current economic expansion close to 10 years old. In July, the economy will almost certainly break the record for the longest period of sustained growth in U.S. history. But no economic law requires economic expansions to die of old age. Some countries with smaller economies have gone decades without a recession.

Douglas Holtz-Eakin, an economist and president of the conservative-leaning American Action Forum, said that the jobs report “should put to rest the notion that the economy is doomed to falter in 2019,” although he added that he “could easily see it in 2020.”

“The chances go up, and the biggest source would be a policy error,” he said, noting two possibilities in which Trump might help cause a downturn — a trade war or another budget battle in the federal government.

Things looked bleaker a few months ago than they actually were because of the partial government shutdown, which lasted a record 35 days into late January. The shutdown deepened pessimism that had set in from December’s stock market woes.

Anxieties about the slowing Chinese economy, aggravated by a trade war with the United States, had also rattled global markets earlier this year.

More recently, however, China’s growth appears to have steadied, thanks partly to government support and an easing of tensions with the U.S. The administration and Chinese leaders have stepped up negotiations toward a possible trade deal. A big Chinese delegation headed by Beijing’s top economic minister is expected to arrive in the U.S. next week for what could be a wrap-up in talks.

The outlook for Europe has improved as well, at least for the moment. Europe’s central bank has resumed stimulus measures to prop up the continent’s growth, and Britain’s tortured exit from the European Union, or Brexit, has been put off until the fall.

But the U.S. economy still has some soft spots. Manufacturing employment has cooled this year after two years of solid growth. And the decline in unemployment last month, from 3.8% in March, was in part due to a drop in the number of unemployed workers looking for jobs.

Another point of uncertainty involves how long the steady job growth can continue. Recent job and wage gains have benefited many lower-educated workers as well as formerly disabled workers, who have come off the sidelines to fill positions. And a greater share of older workers are staying in the labor market, helping to meet employer demands.

But no one knows how much lower the unemployment rate can fall or when employers will hit the wall.

Ben Herzon, economist at Macroeconomic Advisers, a leading forecasting firm, shares the view of most other economists that the economic growth rate will drop from last year’s 3% to about 2% this year, roughly the average over the last 10 years. That’s a healthy rate, he said, but he and other economists worry about the tightened labor market and the possibility that the economy may be reaching capacity.

The Federal Reserve at the start of the year halted its interest rate hikes because of concerns of slowing growth. Some investors — and notably also Trump — have called for the Fed to cut rates again. The Fed this week kept rates steady, and the new jobs report makes further cuts unlikely.

But if signs emerge of the economy overheating, the central bank could pivot back again to raising rates.

“The economy right now is in a good spot,” Herzon said. “But there is a concern that the economy is at capacity, and if you push it harder, that’s where we could get into problems.”

Times staff writers Noah Bierman and Evan Halper in Washington contributed to this article.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.