Supreme Court is not eager to overturn Roe vs. Wade — at least not soon

- Share via

Reporting from Washington — The Supreme Court justices will meet behind closed doors Thursday morning and are expected to debate and discuss — for the 14th time — Indiana’s appeal of court rulings that have blocked a law to prohibit certain abortions.

The high court’s action — or so far, nonaction — in Indiana’s case gives one clue as to how the court’s conservative majority will decide the fate of abortion bans recently passed by lawmakers in Alabama and Georgia. Republican Gov. Kay Ivey of Alabama signed her state’s ban into law on Wednesday.

Lawmakers in those states have said they approved the bans in an effort to force the high court to reconsider Roe vs. Wade, the 1973 decision that legalized abortion nationwide.

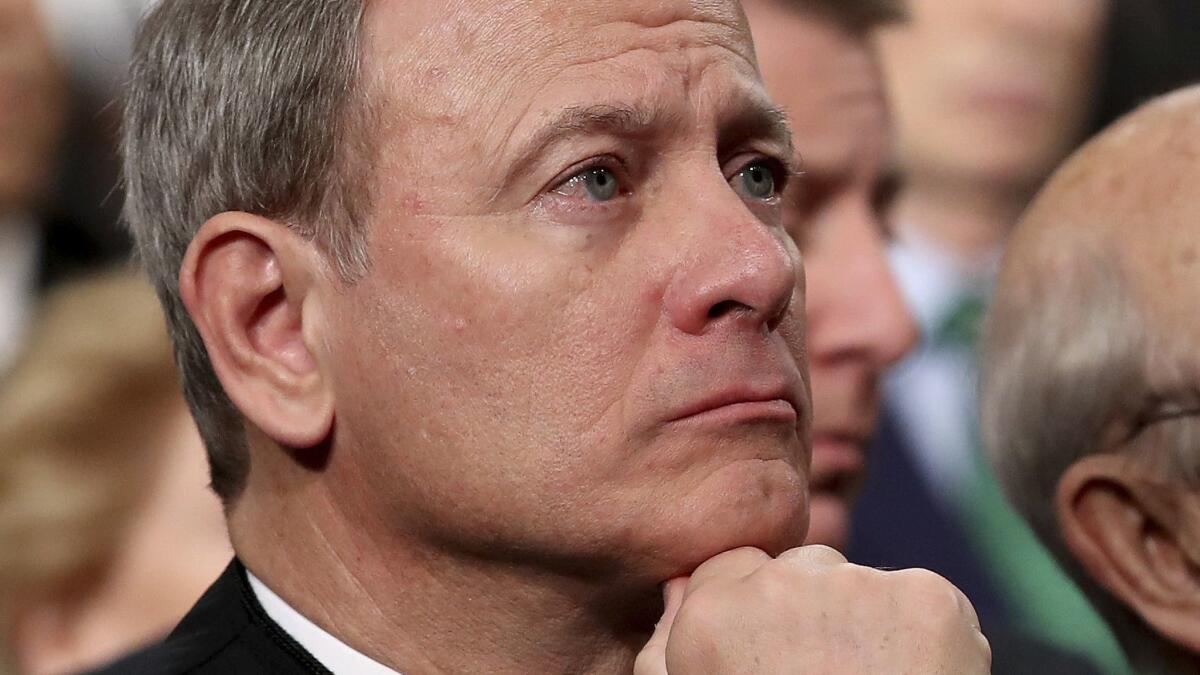

The justices have many ways to avoid such a sweeping ruling, however. And Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr., in his 14 years on the high court, has typically resisted moving quickly to decide major controversies or to announce abrupt, far-reaching changes in the law.

Roberts’ history, along with the court’s handling of abortion cases in recent years, suggests he will not move to overturn the right to abortion soon, or all at once, and is particularly unlikely to do so in the next year or two with a presidential election pending.

Notre Dame Law professor Richard Garnett, a critic of the Roe decision and a former court clerk, said the Alabama lawmakers may be moving too fast.

“It is not clear that the current justices who have expressed doubts about the correctness of decisions like Roe … will want to take up a case that squarely presents the question of whether these decisions should be overruled,” he said. “Instead, they might prefer to first consider less sweeping abortion regulations.”

Roberts is a staunch conservative who has moved the law to the right on a range of issues. He prefers, however, to do so in a step-by-step approach.

Under his leadership, for example, the court’s conservative majority struck down laws that limited campaign spending, including by corporations. But they did so only after several small-scale rulings had chipped away at these laws.

The boldness of the Citizens United decision surprised many, but not those who were closely following the court’s decisions in this area.

The chief justice took the same two-step approach in striking down a key part of the Voting Rights Act and the state laws that allowed mandatory union fees for public employees. In each instance, long-standing precedents were first eroded, then overturned.

In February, the chief justice cast a key vote with the court’s four liberals to keep on hold a Louisiana law that strictly regulates abortion clinics. His vote put off the court’s consideration of the case, June Medical Services vs. Gee, until the fall.

The Louisiana case sets the stage for an election-year ruling on abortion, but only on the question of whether the state may enforce a rule that requires doctors to have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital. Abortion rights supporters say the law would force the closure of most, if not all, abortion clinics in the state.

That case is unlikely to result in overturning Roe, but it could be a stepping stone toward eventually eliminating nationwide abortion rights.

At least three of the justices have indicated a readiness to move more directly to overturn Roe vs. Wade. Justice Clarence Thomas voted to do so shortly after he joined the court in 1992, and Justices Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Neil M. Gorsuch would probably join him. Both are longtime skeptics of the Roe decision.

While the chief justice and Justice Brett M. Kavanaugh would surely agree to limit abortion rights, based on their past statements, neither of them may be inclined now to directly confront the right to abortion.

That could account for the court’s hesitancy to move on the Indiana measure, which was signed into law in 2016 by then-Gov. Mike Pence, now the vice president. It would prohibit abortions for certain reasons, including if a fetus is diagnosed with Down syndrome or any other disability.

The law has not gone into effect because it was struck down by a federal judge in Indiana and by a divided U.S. appeals court in Chicago.

The lower-court judges said the Indiana law clearly conflicted with Roe vs. Wade because it would allow the state, not a woman, to decide which abortions were permitted.

In October, a week after Kavanaugh was sworn in, Indiana’s lawyers asked the high court to hear the case and uphold the law, which it described as designed to “put an end to eugenics abortions.” A second provision of the law would require abortion facilities to treat fetal remains with respect and to either bury or cremate them.

Normally, the justices consider such an appeal for a week or two. If at least four of them vote to hear the appeal, the case is granted a full review. If not, it is denied in a one-line order.

Since Jan. 4, however, the court has repeatedly relisted the case of Box vs. Planned Parenthood for reconsideration.

Recently passed abortion laws in Ohio, Georgia and Alabama, all of which go considerably further than the Indiana law, will be challenged in court, and federal judges, who are bound to follow existing Supreme Court rulings, are almost certain to block them from taking effect.

That will begin a legal process that would send the appeals heading to the high court. But the justices could decide to put those appeals on hold indefinitely while they consider a more limited abortion case, like the one from Louisiana.

If an appeals court strikes down one of the state bans, the justices could also simply decline to consider the appeal, which would not prevent them from revisiting the issue in the future.

In either case, the justices could fairly easily put off a decision on Roe vs. Wade until after the national election in November of 2020.

More stories from David G. Savage »

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.