Decline of white Republicans on L.A.’s northern outskirts puts GOP at risk in midterm election

- Share via

California’s sorely diminished Republican Party has few footholds left in Los Angeles County, and it risks losing its biggest one in the midterm election on Tuesday: the House seat of Rep. Steve Knight of Palmdale.

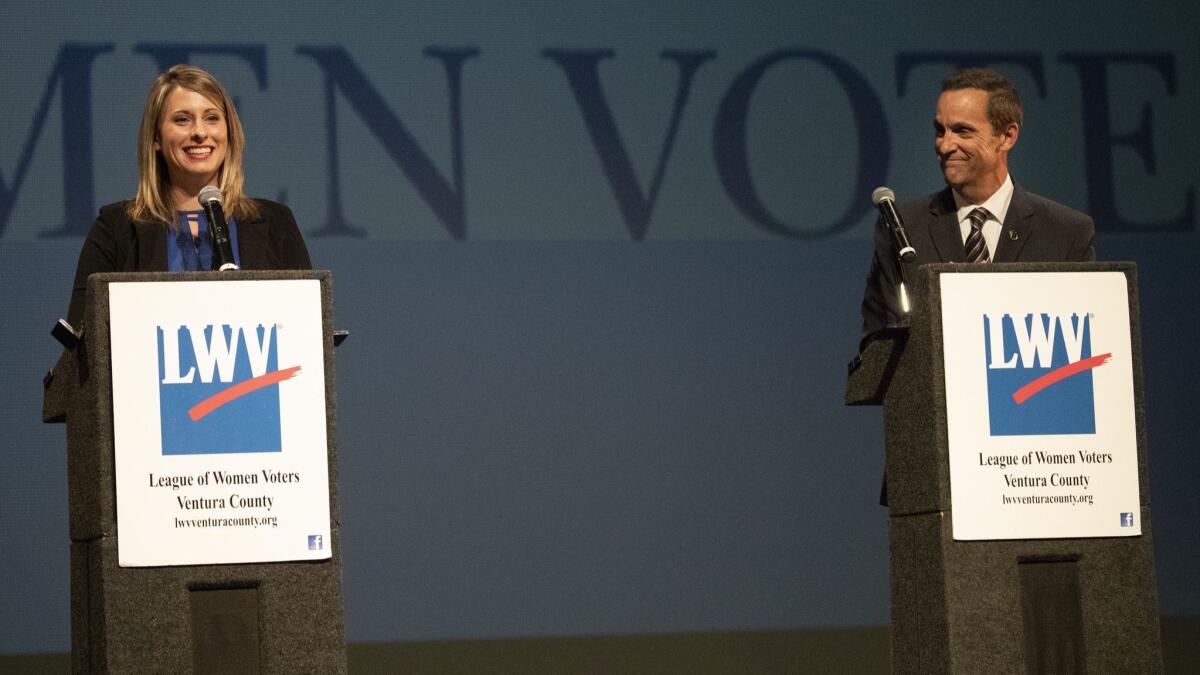

Rapidly expanding racial and ethnic diversity on the northern edge of L.A.’s suburban sprawl has opened a path for Knight’s Democratic rival, Katie Hill, to seize this once-solid Republican turf.

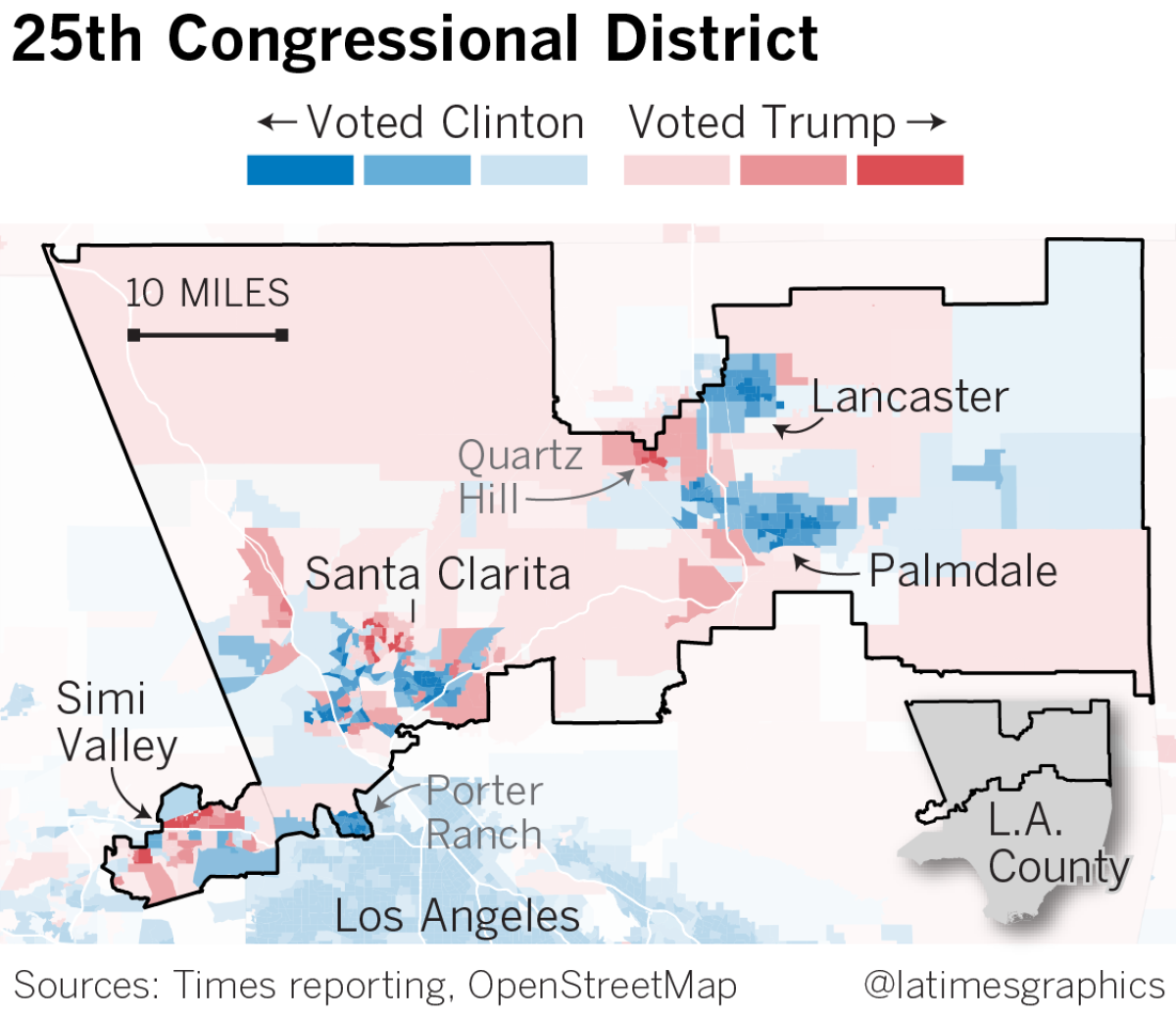

The state’s 25th Congressional District — it covers the Antelope Valley, Santa Clarita and Simi Valley — is a lot less white and less Republican than it used to be. The white share of the population has dropped to 40%.

As the campaign draws to a close, President Trump’s stop-the-caravan, troops-to-the-border crusade could further imperil Knight and other Republicans on the ballot in L.A. and Orange counties. For more than two decades, the party’s belligerence on immigration has proved toxic in California.

Even if Knight wins, Republicans fret that demographic trends will, before long, clear the way for a Democrat to capture his seat.

“It’s not going to get easier in two, four, six years from now,” said Mike Madrid, a GOP strategist. “It’s going to get progressively more difficult.”

In all three of the vast, dry valleys that make up this district where the San Gabriels meet the Santa Susanas, the story is familiar: Tens of thousands of newly arrived families were chased out of Los Angeles by high housing prices. For teachers, mechanics, firefighters, nurses and cops, the move can ensure a middle-class lifestyle now out of reach in L.A.

The most explosive growth is in the Mojave Desert flats of the Antelope Valley, where tumbleweeds blow down the streets on gusty days.

Since 1990, Palmdale’s population has more than doubled, leaping from 69,000 to 158,000. The white share has plummeted from 67% to 22% as Latinos’ has risen from 22% to 59%.

For both Hill and Knight, Antelope Valley roots run deep. The daughter of a police officer and a nurse, Hill, 31, grew up in Rosamond, on the outskirts of Lancaster, and in Santa Clarita.

Knight, 51, was born on Edwards Air Force base. His father, William J. “Pete” Knight, was a test pilot who in 1967 broke a world speed record, still unmatched, in an X-15.

“Nobody’s ever flown a plane faster than my father,” Knight said.

Pete Knight, a state lawmaker who died in 2004, remains a local icon. In Palmdale, a high school is named after him, and a display in a flight museum pays tribute to him, no small gesture in a community anchored by the aerospace industry.

“His name still counts for a great deal,” said Dennis Anderson, former editor of the Antelope Valley Press.

The younger Knight, an Army veteran, served for 18 years as a patrol officer in the Los Angeles Police Department, commuting from Palmdale to the San Fernando Valley. His congressional district is packed with residents who work in law enforcement.

With his short haircut, loose-fitting suits and just-the-facts-ma’am speaking manner, Knight could pass for a cop on “Dragnet,” the TV series popular in the 1950s and ’60s. He punctuates conversations with “gosh” and “dog-gone.” He and his wife, Lily Knight, a Chilean immigrant, have two sons.

In Congress, Knight sides largely with his party’s conservative wing, a stance that poses growing risks in a district where Democrats now outnumber Republicans. He backed the GOP’s attempts to repeal President Obama’s healthcare law and voted for Trump’s tax overhaul.

Knight has tried to distance himself from Trump on immigration. He opposes the separation of families at the Mexican border and backs legal status for immigrants who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children.

But his support for Trump’s rollback of environmental rules and his opposition to abortion rights, even in cases of rape or incest, have drawn attacks from Hill.

Hill would be one of the youngest members of Congress if she wins. She earned a master’s degree in public administration at Cal State Northridge, then quickly rose through the ranks at PATH, a Los Angeles nonprofit that serves the homeless. Hill was one of its top executives when she quit last year to run for Congress.

She and her husband, Kenny Heslep, live on a farm in Agua Dulce, a small mountain town off the 14 Freeway. Their goat, Greta, serves as a lawn mower, Hill said. They also have a horse and turkey, along with a dozen chickens and four dogs.

The couple keep firearms in their house, as Hill sometimes mentions when she calls for gun control measures and faults Knight for his “A” rating from the National Rifle Assn.

“As a gun owner, I’m able to say to fellow gun owners, look, this isn’t about trying to take your guns away,” Hill said.

Drawing on the anti-Trump fervor of Democratic donors nationwide, Hill has raised $7.3 million, a staggering sum for a House candidate and more than triple Knight’s $2.4 million.

Outside groups have dumped another $17.8 million into the contest, one of the most hard-fought in the country as Democrats try to gain the 23 seats they need to take control of the House.

Like many Democrats in tight races, Hill is counting on overwhelming support from suburban women with college degrees, but the district’s blue-collar cast blunts that advantage in her case.

She also needs strong support from Latinos, especially in the Antelope Valley neighborhoods where they’re most concentrated. Voter turnout there is a steep challenge.

“Habla español?” a man asked Hill at a recent Palmdale potluck celebration of Cafe Con Leche, a bilingual talk-radio show in the high desert.

“Muy poquito,” Hill responded.

Working the tables as the crowd dined on tamales, empanadas, fried chicken and rice, Hill told Palmdale housekeeper Olivia Alfaro: “I care about education, healthcare and housing.”

Alfaro, 40, is not yet a citizen, so she can’t vote. Her family moved from L.A. to Palmdale 14 years ago so they could pay lower rent for a bigger apartment. Her two grown sons can vote, and the whole family loathes Trump. “He thinks he’s working in the circus,” she said.

The Antelope Valley is the most strongly Democratic part of the district. The more prosperous Santa Clarita swings between the two parties, and Simi Valley remains a GOP stronghold, especially around the gated communities of its highest hillsides.

Since Santa Clarita’s founding in 1987, a boom in new tract houses and shopping malls has transformed the former cluster of small towns — Newhall, Saugus, Valencia and Canyon Country — into the third-largest city in L.A. County after Los Angeles and Long Beach. Its population has nearly doubled to 211,000.

Since 1990, the white share has fallen from 81% to 51%. Santa Clarita is now 32% Latino, 10% Asian and 3% black.

Republicans run the City Council, but voter registration is almost evenly split between the parties, and Santa Clarita narrowly favored Clinton over Trump.

“The conservative guard are still treating Santa Clarita as a small town,” said Stephen Daniels, host of the Talk of Santa Clarita podcast and publisher of the Proclaimer, a local news website. “Ironically, they’re working with developers to keep expanding the city — building and building and building.”

Simi Valley is a smaller, more established and more firmly Republican suburb in Ventura County.

“It’s clean, it’s quiet, it’s safe,” Evan Steinmetz, an executive recruiter in a Red Sox cap, said while watching a World Series game at Cronies Sports Grill off the 118 Freeway.

Steinmetz, a 26-year-old Republican, moved to Simi Valley from L.A. (“Way too fast. Too many people. Too much clutter. Too much commotion.”) He plans to vote for Knight. (“Military. LAPD. The vets program that he’s trying to fix.”)

Simi Valley is changing more slowly than the rest of the district; its growing Latino population tops 25%.

Dan McDougall, 59, runs a military surplus store in a strip mall with his wife, Mercy. A bumper sticker in the storefront window reflects his conservative politics: “The bigger the government, the smaller the citizen,” it says. McDougall, an independent, finds Trump refreshing, and he’s voting for Knight.

Next door is Taqueria El Maizal, where immigrants speaking Spanish dine next to longtime white residents. McDougall remembers when the taqueria was a Fosters Freeze. He welcomes the neighborhood’s immigrants.

“It’s all good,” he said.

As Knight tries to keep up with the district’s transformation, he stays focused on tending to his Republican base. At Republican women’s lunches, supporters have been sharing their nervousness about a storm of Democratic ads attacking him.

“We’ll be OK,” he told a local college president at the Antelope Valley Country Club in Palmdale. “Or we’ll play a lot of golf.”

Twitter: @finneganLAT

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this story.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.