Bill Clinton, the natural, reaches out to voters in places that love Trump

- Share via

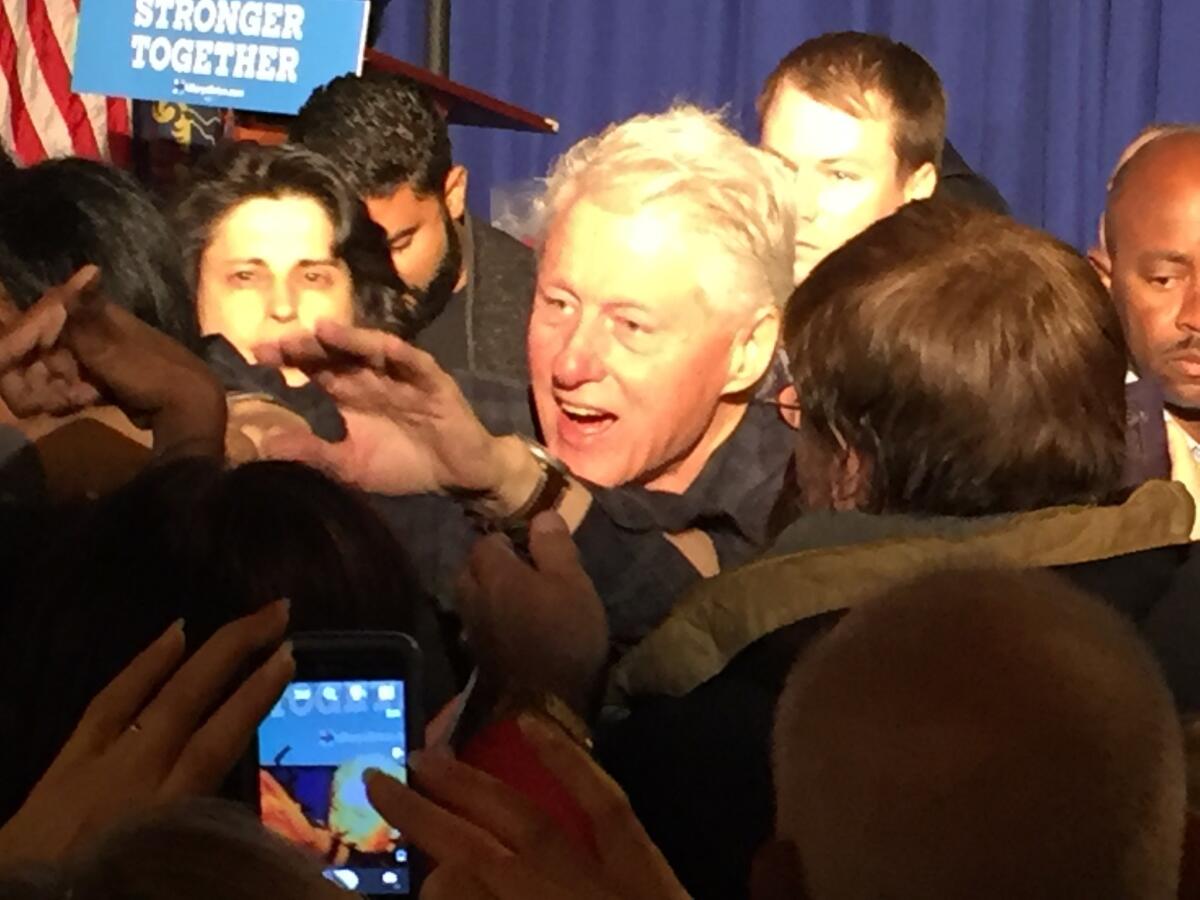

Reporting from CINCINNATI — Tall and vegan-slender since his quadruple bypass, the former president steps off the stage and meanders down a rope line. His thick shock of silver hair disappears as he bends down to shake hands with a child, then reemerges, only to disappear again in a sea of people, sometimes three deep, reaching for him.

Bill Clinton is casually dressed in an open-collar shirt and jacket, his pace as languid as his familiar Southern drawl. He chats with his ardent fans at a megachurch on the outskirts of Cincinnati and poses for selfies.

He seems to be enjoying every moment, every speck of attention, as he campaigns in battleground states for his wife, Hillary, who is seeking the presidency. Over two days last week, he visited six cities and towns in Ohio and Pennsylvania. He popped into universities, union halls, churches and auditoriums.

“They send me to where her opponent is strong,” he told a crowd of still-sleepy students one morning in Cleveland.

Onstage, sometimes he pauses, midsentence, and it seems like maybe he’s lost his thread. That can happen at the dawn of your eighth decade. But he’s just considering his next line, and he always finishes his thought.

He no longer fires up a crowd like the Obamas, undisputed rock stars of the Democratic campaign trail.

But he brings something to the race that the Obamas cannot: his white, working-class bona fides.

Clinton is not just the country’s most popular ex-president, he is also the Democrats’ best bridge to Donald Trump’s base of blue-collar men who are angry about the way they’ve been buffeted by a changing economy and the country’s relentless demographic changes.

“I spent my life watching people play my working-class white family off African Americans,” Clinton said in Cincinnati. “No, you can’t have a raise. But you can look down on these people over here.”

During his administration, he reminds the crowd, the country experienced its longest economic expansion in history, and its lowest unemployment rates in 30 years. And this, ultimately, is what Clinton is selling. Vote for us — well, her — and it can happen again.

In Aliquippa, a western Pennsylvania steel town, Michael Good, a 47-year-old steelworker, waited to hear Clinton. Good is like many of the Rust Belt voters who have flocked to Trump. Over the years, he has faced layoffs and a seesawing income. But, he said, “I lived well under Bill Clinton.”

::

It’s not a shock that the man who is the nation’s foremost symbol of political baggage, of truth-shading, of the tarnishing effect of the unrestrained libido, should preach the virtue of turning the other cheek.

He gets plenty of chances to do that in these last, pitched moments of the 2016 campaign. On a recent afternoon, one such opportunity presented itself, about five minutes into his speech in Duncansville, in central Pennsylvania.

Several hundred had gathered to see him in a union meeting hall. Clinton was mocking Trump’s charge that Hillary Clinton has been in public service for three decades and failed to fix what ails the country.

“She did have some influence when I was president,” Clinton said in that familiar, hoarse voice. “We tried to pass healthcare. We had the longest economic expansion in history; everyone’s income rose. Golly, I thought I did some of it. Turned out, she was in control the whole time.”

In the back of the hall, a young man ripped off his Hillary T-shirt to reveal a second T-shirt with Bill Clinton’s face and the word “Rape.”

“You’re a rapist!” the man yelled. The crowd booed. Two officers hustled him out. Clinton never stopped talking.

Toward the end, he acknowledged the outburst: “I’m tired of all this acid being poured down people’s throat. In the end, we all gotta get up in the morning. I want you to think about this, and talk to people like that fellow who screamed at me. If somebody says something hateful to you, tell them, ‘Unlike you, we actually want you to be part of our future.’”

This genteel style, a counterpoint to the rough tone of Trump rallies, extends to his rope-line conversations as well.

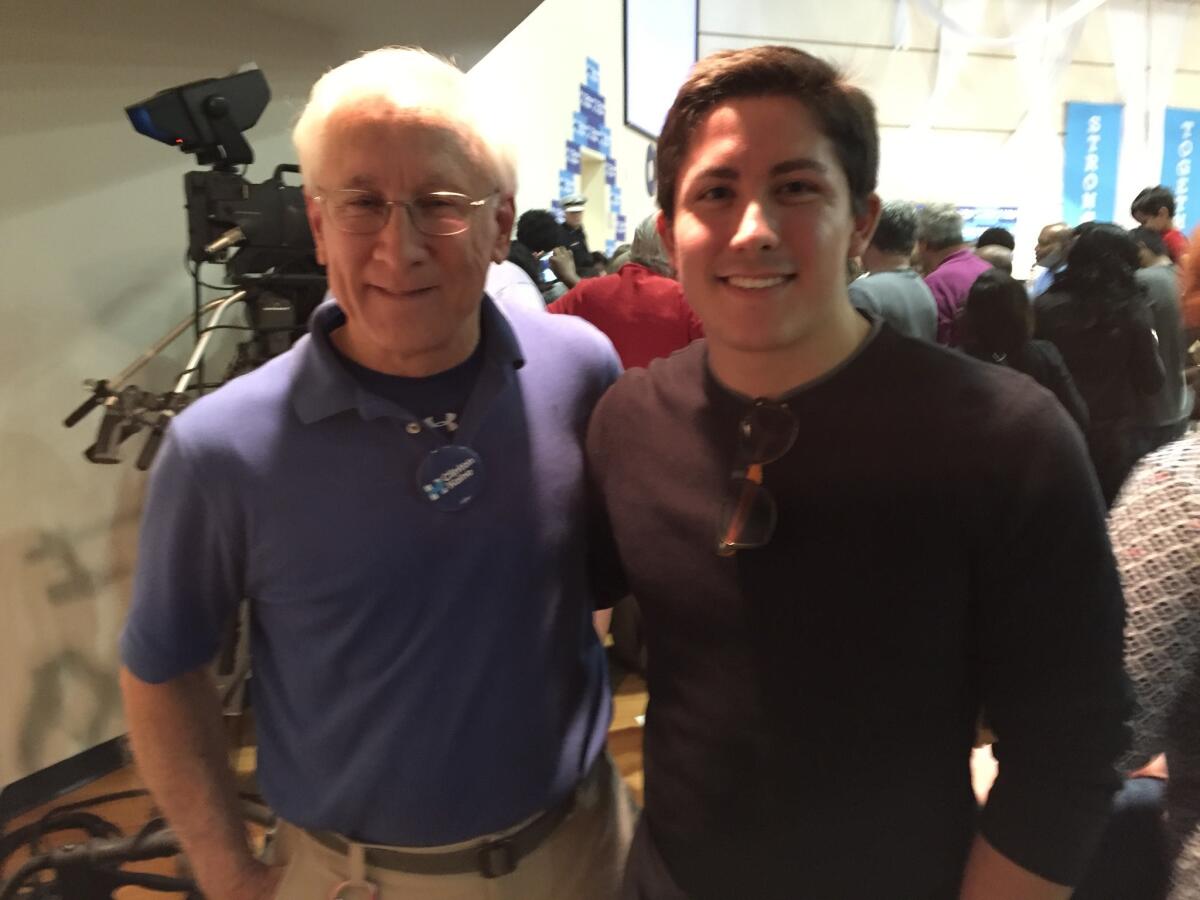

After his speech at the Cincinnati megachurch, Clinton spent an unusually long time with Mike Travanutti, 63, a retired financial manager. Until 2008, Travanutti was a lifelong Republican and “Bill Clinton hater.” Disgusted by the way Republicans turned on Colin Powell for supporting Obama, and dismayed by the viciousness of the attacks on the Clintons, he turned off conservative talk radio.

He apologized to Clinton “for drinking the right-wing Kool-Aid in the ’90s.” He told Clinton he voted against Al Gore in 2000 because of the president’s sexual misconduct with a White House intern. “I told him, ‘Everything I thought about you before was wrong.’”

Clinton held onto his hand.

“He said, ‘I forgive you,’’’ Travanutti said. “I thought I was going to cry.”

::

While every Bill Clinton speech is an encomium to the superior ideas of his wife, the glory days of his own tenure (though with never the slightest allusion to his impeachment), and the promise of a brighter future, it is also an unabashed critique of Trump.

The trick to going high when they go low, it seems, is to never say the other guy’s name.

Over two days in Pennsylvania and Ohio, Clinton never once publicly uttered the words “Donald Trump.” But he never stopped slamming “Hillary’s opponent,” the man who has, with gusto, reopened the tawdriest political wounds of the ’90s.

He never accused Trump of being a racist. He didn’t have to.

“I am a 70-year-old white Southerner,” he told the college students in Cleveland. “I know what ‘Make America great again’ means. It means I’ll give you the economy you had 50 years ago when you had a good, middle-class lifestyle and you felt good when you got up in the morning. And I will give you the society you had back then. I will move you up on the social totem pole and make other people slide back down. That’s a big part of this, and you know it.”

In Aliquippa, he accused Trump of building two projects with “illegal imported Chinese steel.”

“The steel was proved to be sold in America at a price lower than it cost the Chinese to make it in the first place,” Clinton said. “That’s like going into a country and firing a missile at a plant and taking people’s jobs away.”

“Lock him up!” yelled a man in the crowd, echoing the anti-Hillary chant that has become a staple of Trump rallies.

“No,” Clinton replied, “that’s the kind of stuff they say. I want you to lock him out of the White House.”

::

His loose approach on the trail can backfire. Last month in Michigan, his inartful description of rising Obamacare premiums was put to instant use in Republican ads.

But people who assumed the Big Dog would be muzzled — as he was in 2008 after calling Obama’s Iraq war opposition “the biggest fairy tale you ever saw” — are wrong.

Until election day, he will keep up his frenzied schedule of three appearances a day, flying private jets between stops.

Holding a microphone in one hand, his other hand casually in his pocket, Clinton still exudes the qualities that have made him such a singular politician — the ability to convey deep empathy for Americans struggling with economic dislocation, combined with a mastery of policy and simple-sounding solutions to vexatious problems.

He spoke of “small towns, rural areas losing manufacturing jobs and other jobs, and they don’t bounce back in a hurry.... It’s a terrible problem. And it’s fueling a lot of the road rage in her opponent’s campaign.

“And I get it. The worst thing in the world is to get up every single morning and start the day by looking in the mirror and know that there is not one single, solitary thing you can do to make tomorrow better than today. The question is what would fix it? She’s the only person got a plan to do it.”

Clinton also sprinkles in unexpected tidbits: “Pennsylvania Dutch” are actually German. Canada has one of the biggest Ukrainian populations outside of Ukraine. White working-class Americans are the only group whose life expectancy is going down. He owns a sculpture by newly minted Nobel laureate Bob Dylan, a gate made of old farm implements.

Hillary Clinton supporters may or may not have warm feelings about her, but they love him.

“He’s still got it,” said Joe Wagner, a 61-year-old construction worker who lives among Trump supporters in Batavia, a Cincinnati suburb. “He’s just so good.”

Whether his wife makes history or not, you get the sense that Bill Clinton will always be a welcome sight in these places. He embodies the ’90s, and for most Americans, the ’90s were pretty good.

As people started to file out of the Word Family Life Center megachurch, police officers blocked the doors. Dozens already outside were told to stay put. There was only one driveway into the church’s parking lot, and no one would be allowed to leave until Clinton’s motorcade departed.

Rolling past the crowd, Clinton lowered the window of his black SUV, smiled and waved. The crowd waved back.

Twitter: @AbcarianLAT

ALSO

The polls might seem wild right now, but this election is closing a lot like the last one did

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.