Late-night phone calls and door-knocking -- how Democrats counted the results in Iowa

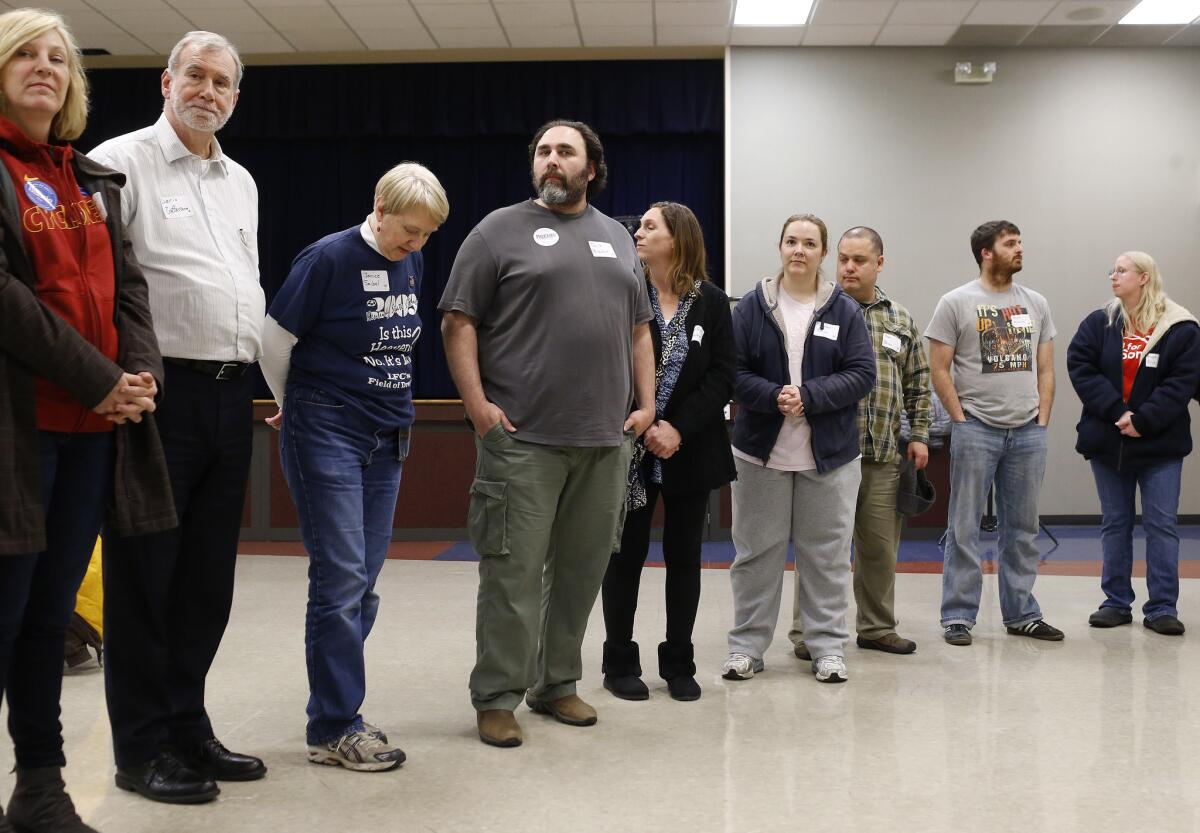

Supporters of candidate Bernie Sanders stand in line while they are counted during a Democratic Party caucus in Nevada, Iowa, on Monday.

- Share via

Reporting from Des Moines — The phone rang at 1 a.m. on Tuesday at the home of Gary Gelner, the Democratic chairman of Iowa’s Hancock County. State party officials wanted the results from two caucus precincts in his rural swatch about 100 miles north of the state capital.

For one location, the state party simply wanted to confirm the outcome; a razor-thin margin separated rivals Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders in the first nominating contest of the 2016 presidential election, and a correct count was crucial. But in the second, they had not received any results at all.

Turns out, no one had shown up.

“I had to make a phone call at 1 o’clock and report the results of 0-0-0” back to the state party, Gelner said in an interview Tuesday.

Once again, the Iowa caucuses were marred by reporting problems, but unlike four years ago, the Democrats were the party struggling Monday. Party leaders were unable to track down tallies in several precincts, meaning they could not officially name Clinton the winner until just before noon on Tuesday, more than half a day after the caucuses ended.

Such problems are inherently baked into the caucus process, political experts say – despite technological innovations and procedural improvements, the system relies on hordes of volunteers to carry out a complicated ritual in nearly 1,700 schools, homes and church halls across the state.

Sometimes, they go to bed without reporting their tallies, which happened in more than one precinct Tuesday night. In one instance, party officials sent someone to knock on a precinct chair’s door after midnight in Des Moines, seeking results. She did not answer.

“It’s normal that we have to track down some of the volunteers,” said Norm Sterzenbach, a former executive director of the Iowa Democratic Party, who noted that it was also a problem in 2008, the last time the Democrats had a contested caucus.

Large turnout can rapidly add to the duties of a precinct chair, who is not only responsible for running the caucus but also the event site.

“It’s easy to get distracted,” Sterzenbach said. “In 2008, some of them finished all the business of the caucus, were cleaning up and putting the chairs away. We had a few that went home. We had to track them down and they said, ‘Oh, shoot, I didn’t get the results in.’”

Similar miscues were magnified this year by the closeness of the race. Ultimately, Clinton edged Sanders by 0.3%.

“Any time any election comes down to [a fraction] of a percent, there are going to be some problems,” said Pat Rynard, who runs the political website Iowa Starting Line and worked as a Democratic organizer in the state for a decade.

Larger problems plagued the GOP four years ago, resulting in Mitt Romney being wrongly labeled the victor on caucus night. More than two weeks later, state GOP officials announced that former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum had actually won, but at that point, Romney was riding the momentum from his Iowa win toward the party’s nomination.

Critics of Iowa’s first-in-the-nation status pointed to 2012 as a reason to stop allowing the state to hold the first presidential nominating contest. Democrats here expect similar scrutiny this year.

“The caucuses weren’t designed for this kind of burden,” said a veteran Democratic operative who would not be named questioning the party’s preparations. “I’m sure there’s going to be quite a few questions about what kind of boiler room was prepared.”

Join the conversation on Facebook >>

Caucus backers counter that races managed by government agencies can take weeks to finalize a tight race, and that such systems themselves can be rife with problems – such as the Al Gore-George W. Bush fiasco in Florida in 2000.

That election controversy centered on the use of paper ballots and the detritus from hole punches that introduced the country to the vote-counting term “hanging chad.”

In Iowa this year, the memorable image may be the caucus quirk of the “game of chance,” in which a coin toss is used to break ties to award county delegates, which are worth such a small fraction of support that they would not have changed the results, according to several state party officials and Democratic strategists.

It wasn’t clear how many county delegates were awarded by coin toss – the state party counted seven instances; unconfirmed reports of others surfaced.

Sanders told reporters Tuesday in Keene, N.H., that his campaign wants to review cases in which delegates were awarded based on a coin flip.

“Not the best way to do democracy,” he said.

Mehta and Megerian reported from Des Moines. Times staff writer Evan Halper in Keene contributed to this report.

For more political coverage, go to www.latimes.com/politics.

MORE FROM POLITICS

A dramatically reshaped presidential race drives into New Hampshire

Marco Rubio is peaking as planned, but will ‘Marcomentum’ continue?

An Iowa caucus yields scrums, bribery and cajoling: ‘The only thing people get excited about here’

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.