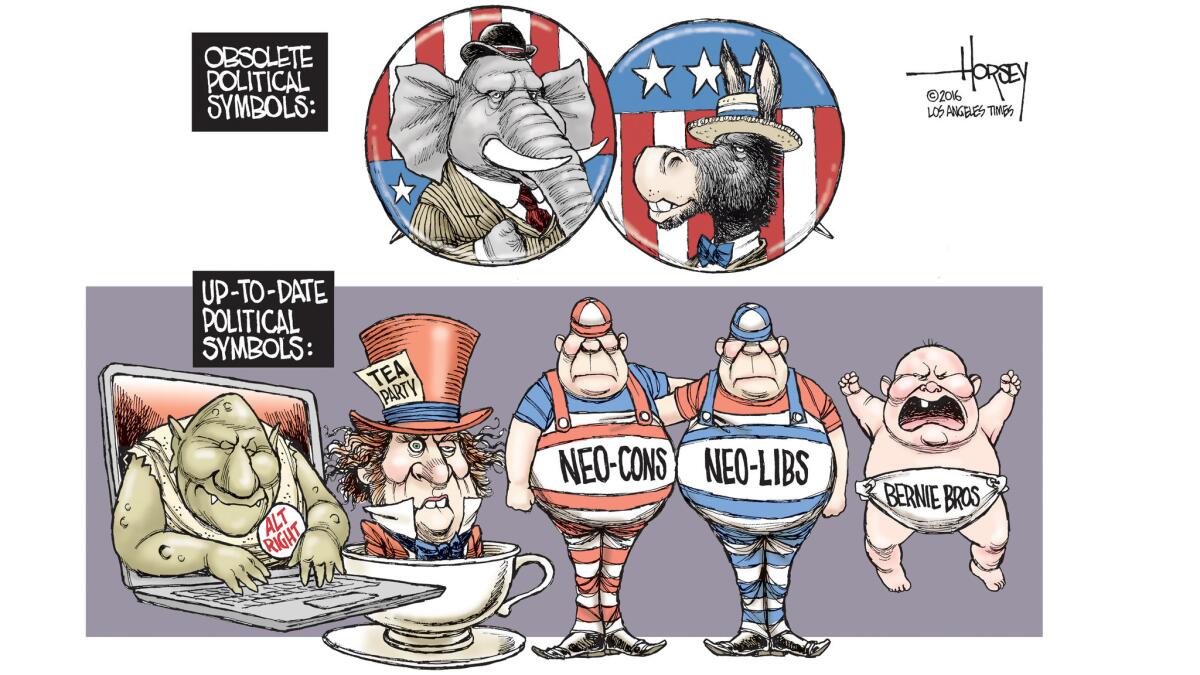

Elephants and donkeys are lame symbols for U.S. politics in 2016

- Share via

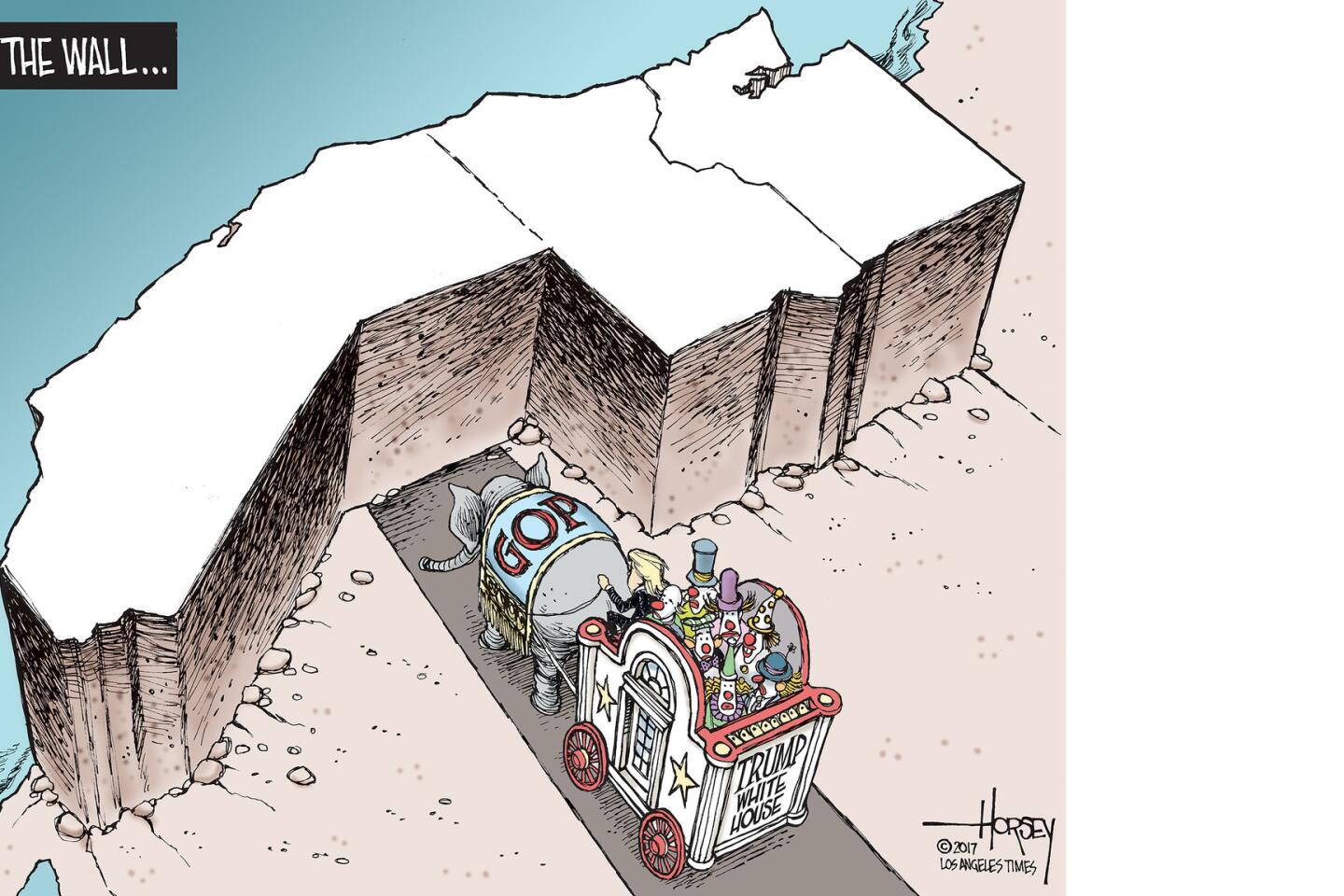

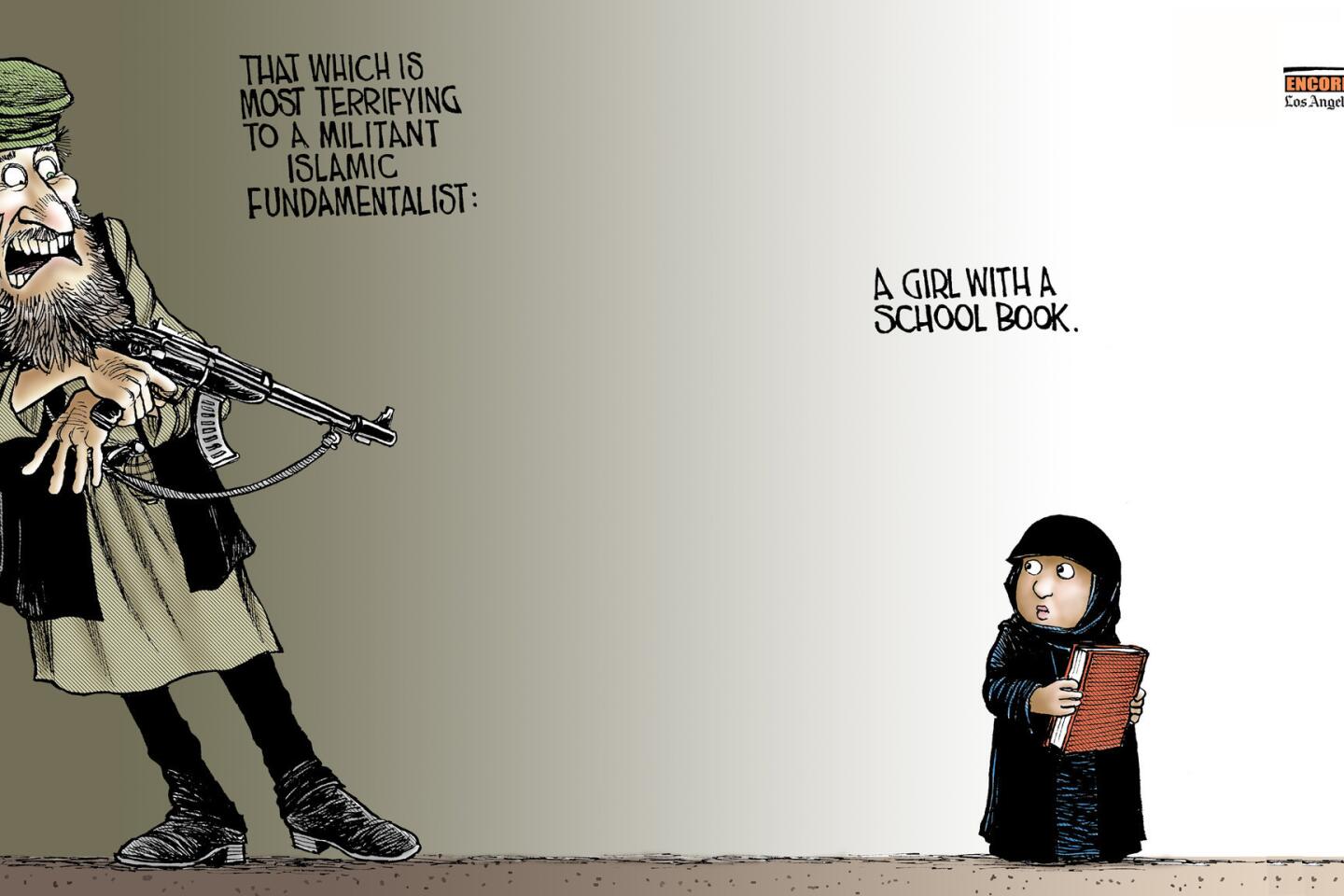

Thomas Nast, the 19th century political cartoonist who, even today, remains the most famous practitioner of the “jugular art,” drew the first full realization of the two enduring symbols of our two major political parties, the Republican elephant and the Democratic donkey. The elephant and donkey had a good long run, but, in the context of the 2016 presidential campaign, they are more anachronistic than accurate.

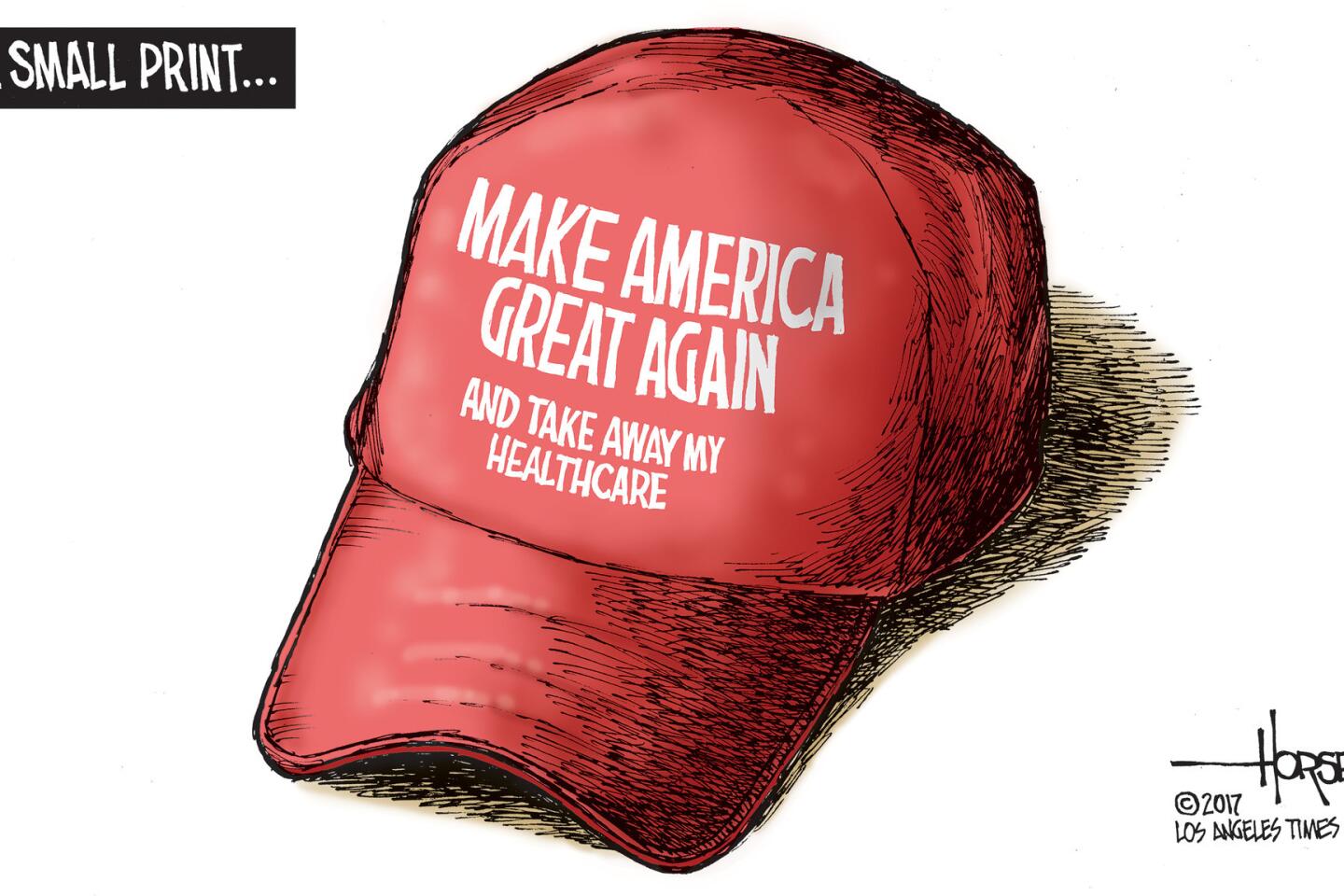

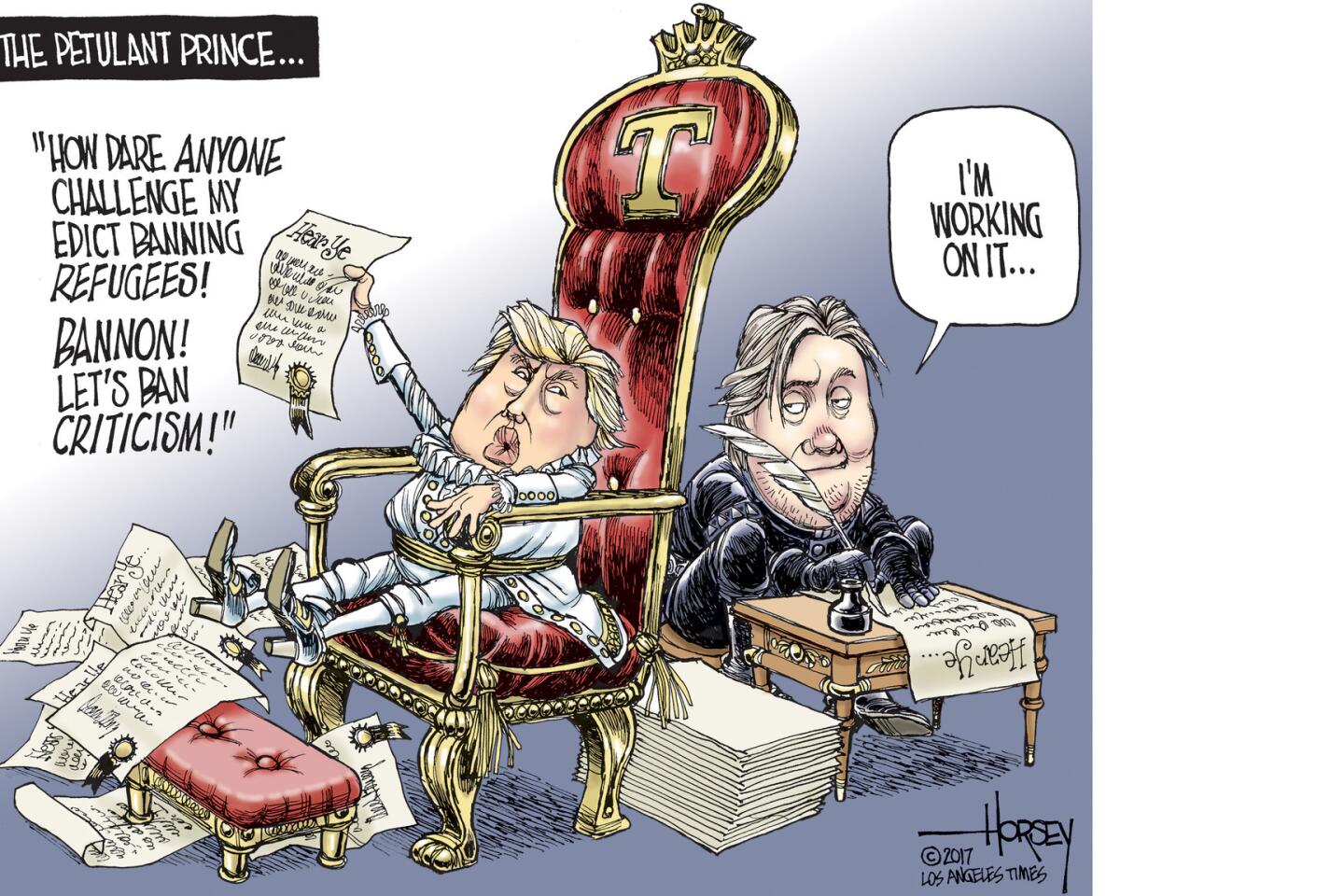

At a time when the Republican Party is so splintered, which Republicans does the elephant represent? The dwindling establishment? The rebellious party base? The do-nothing congressional wing? The “movement” conservatives?

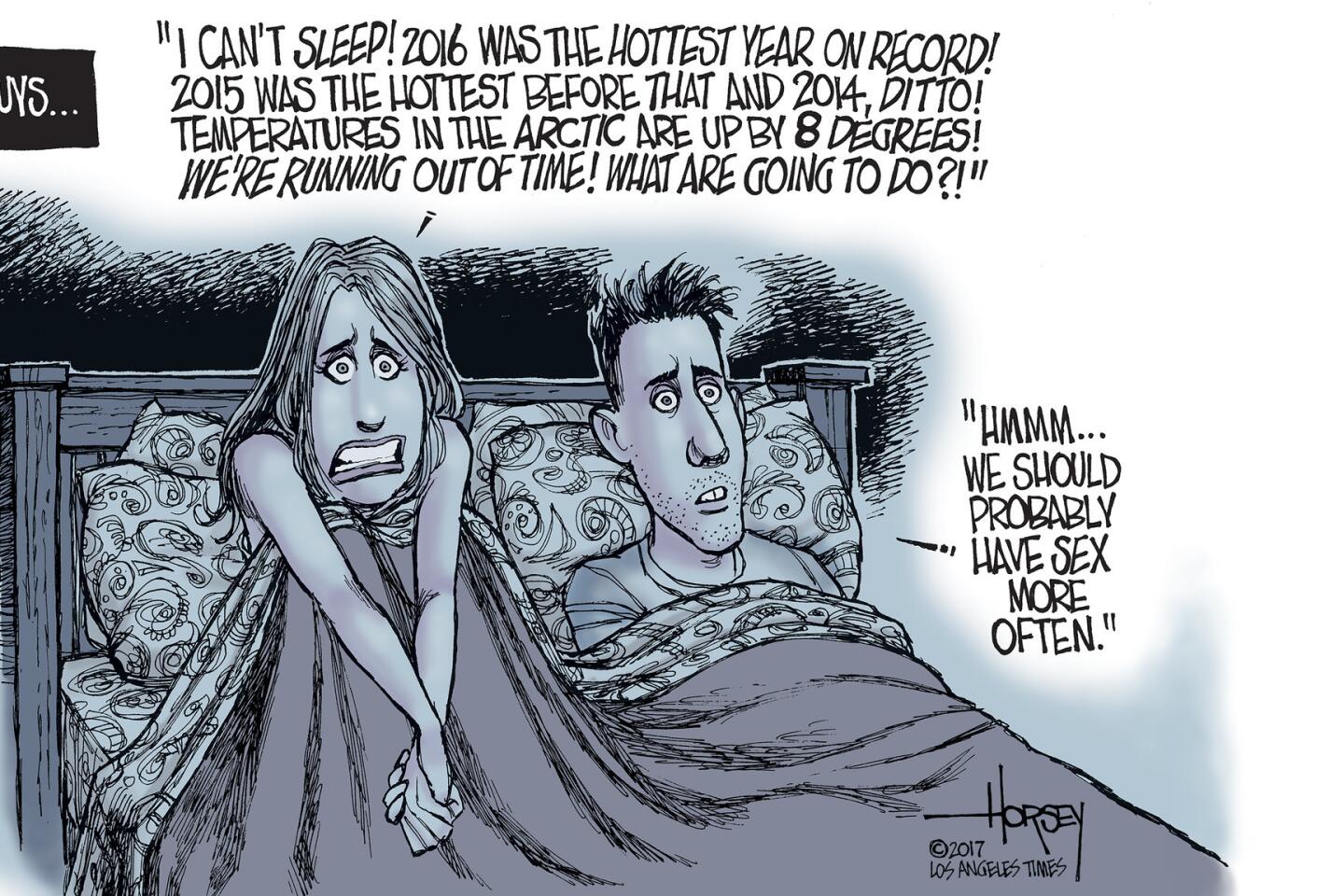

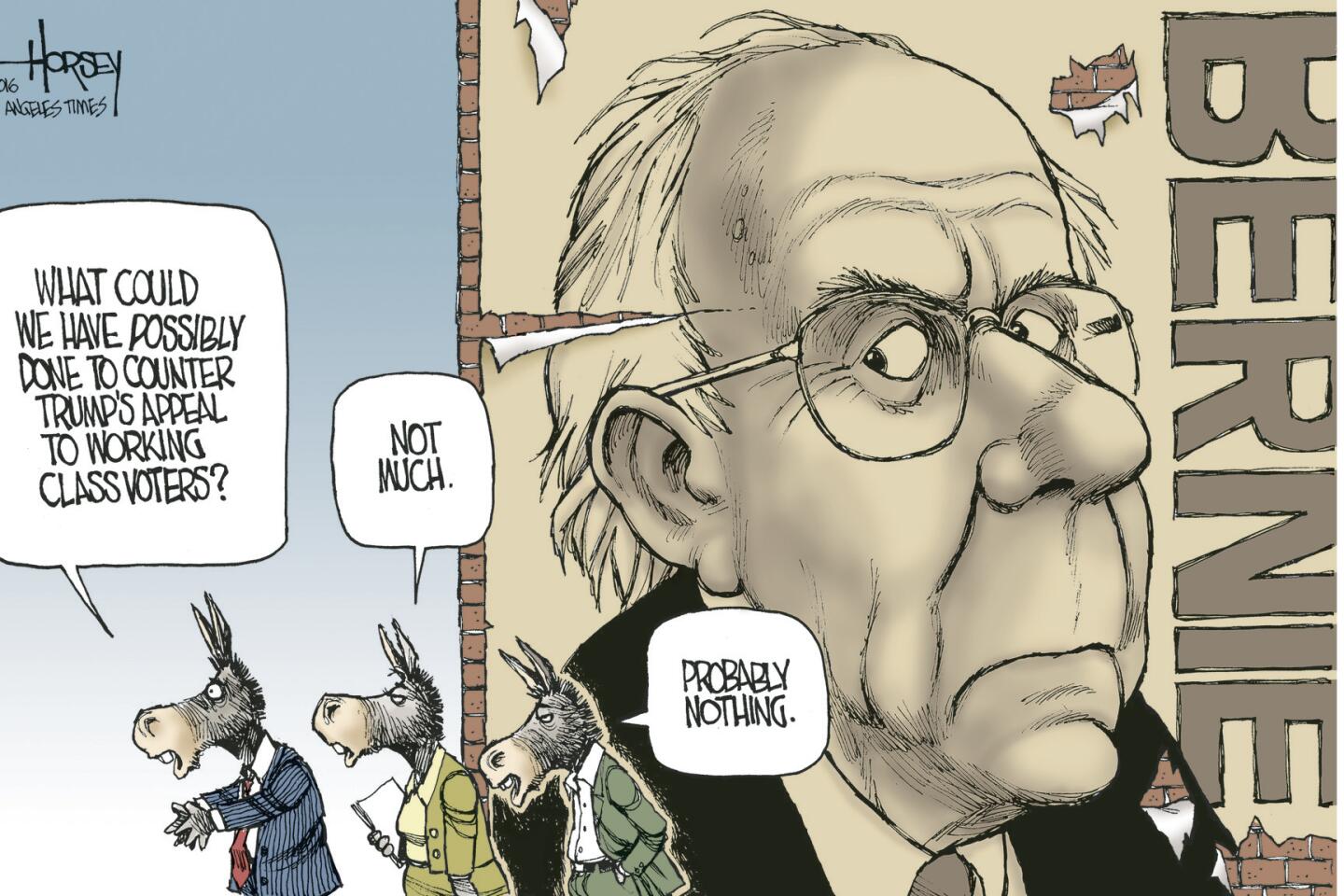

And does the Democratic donkey have any meaning for the millions of people who voted for Bernie Sanders? He, himself, is a newbie Democrat and many of his supporters — including a big share of his delegates at the Democratic National Convention — feel little, if any, affinity for the party the donkey symbolizes.

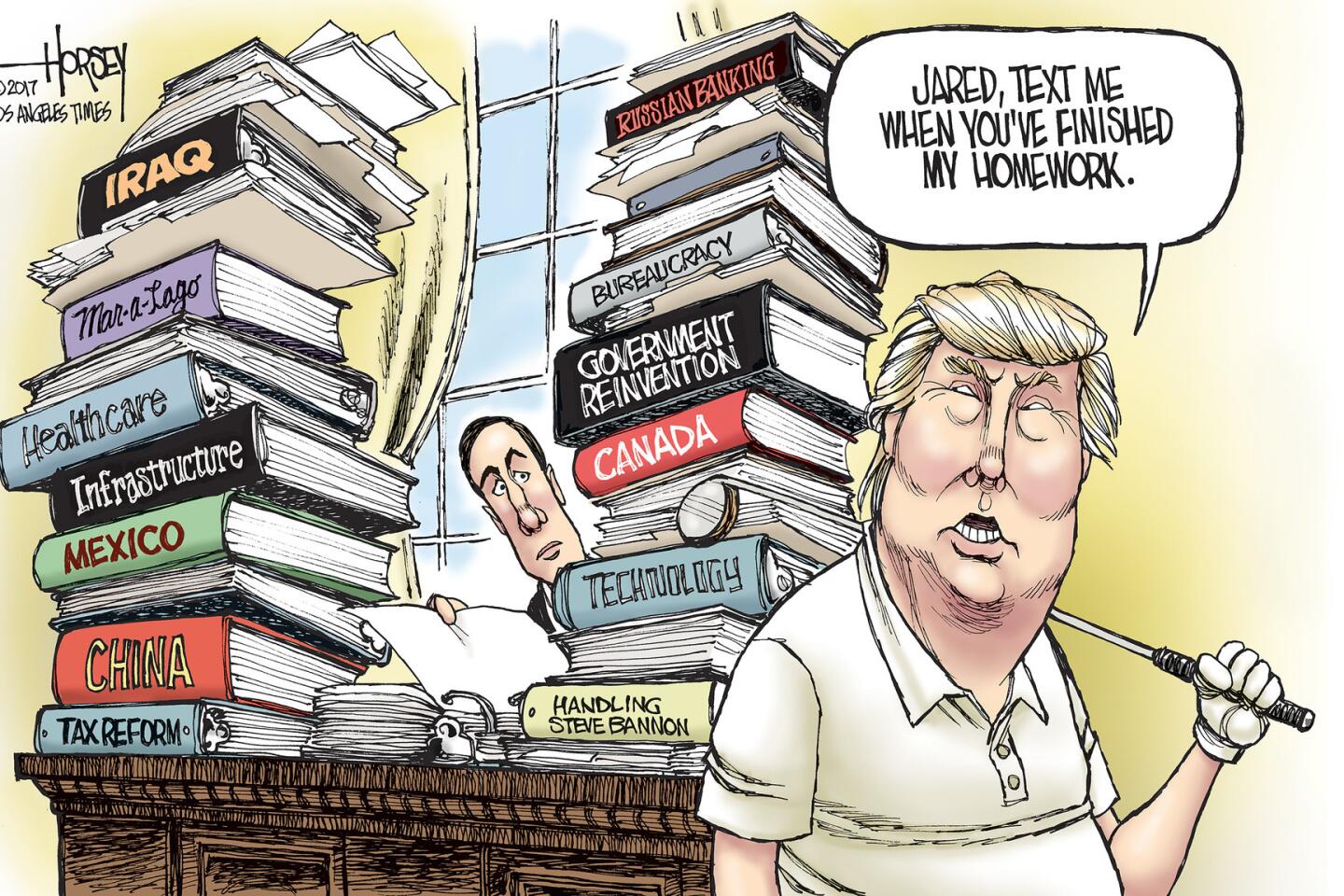

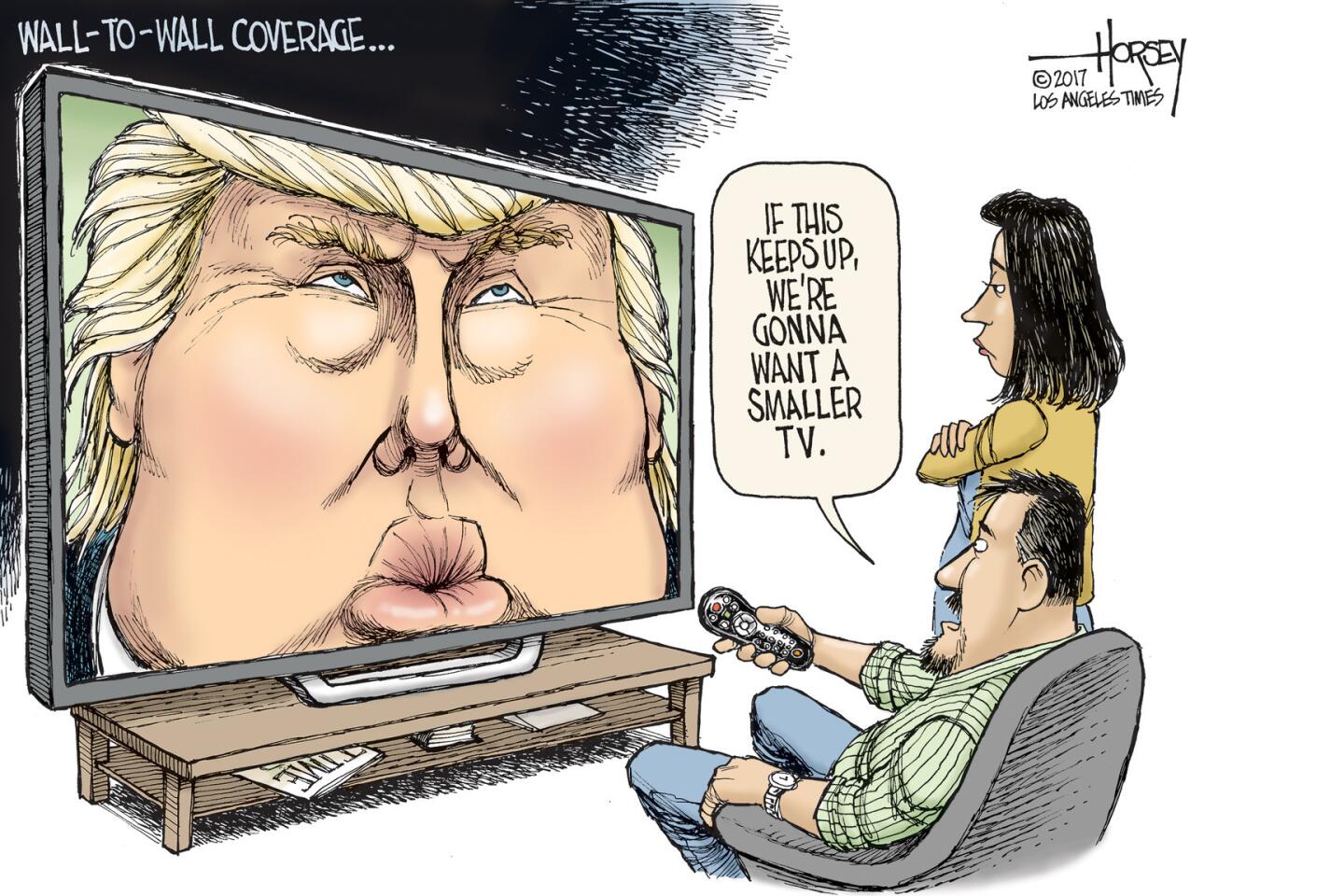

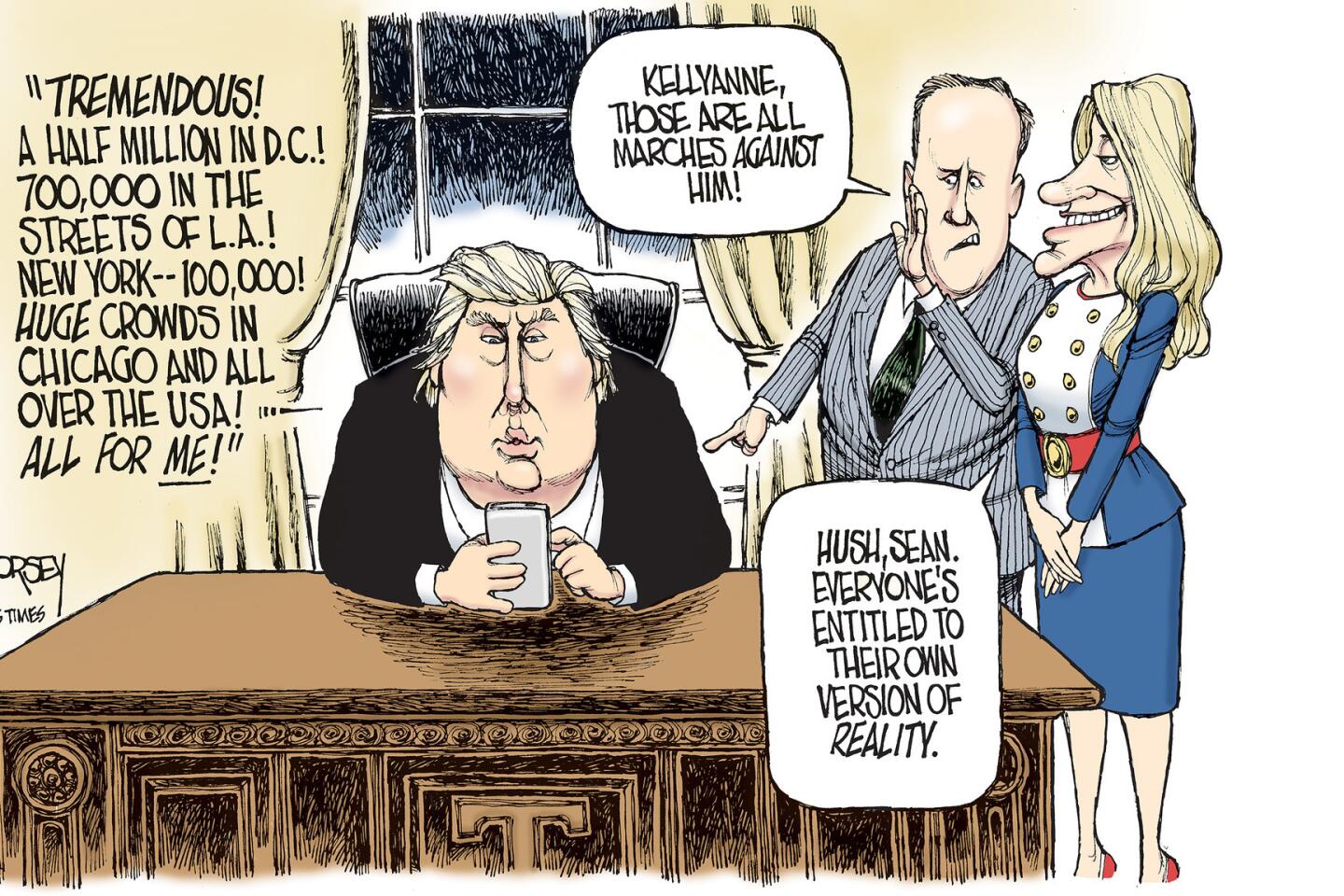

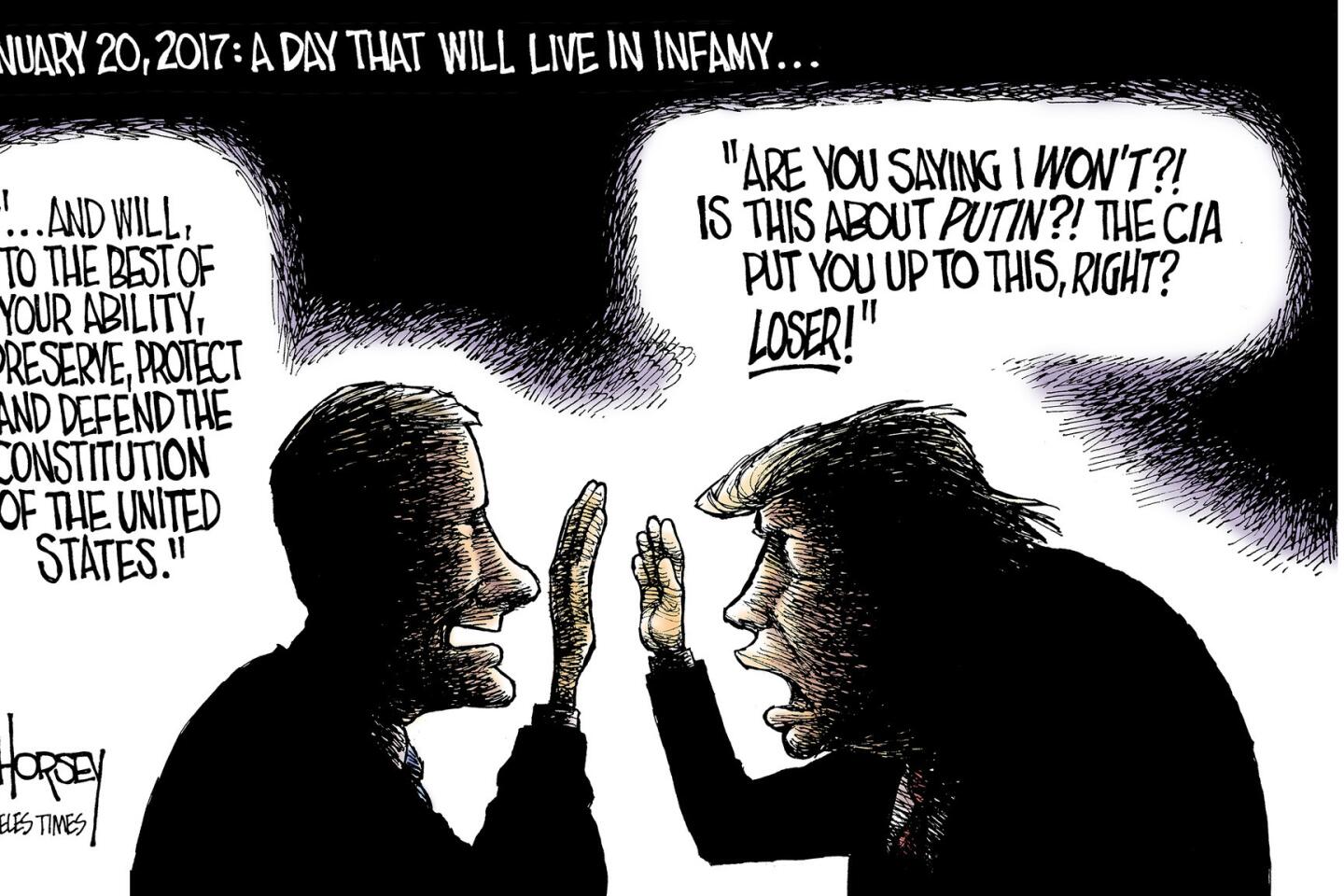

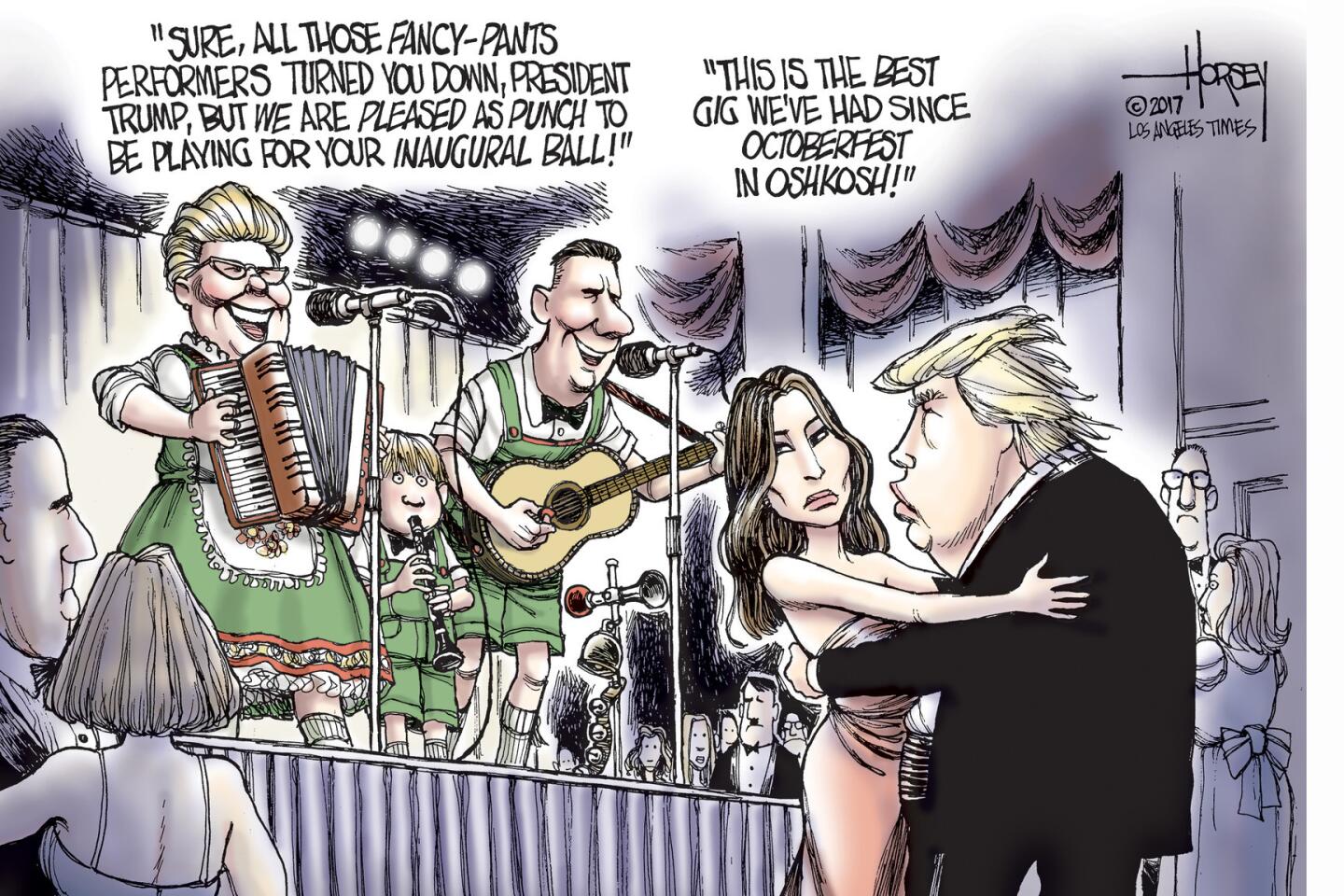

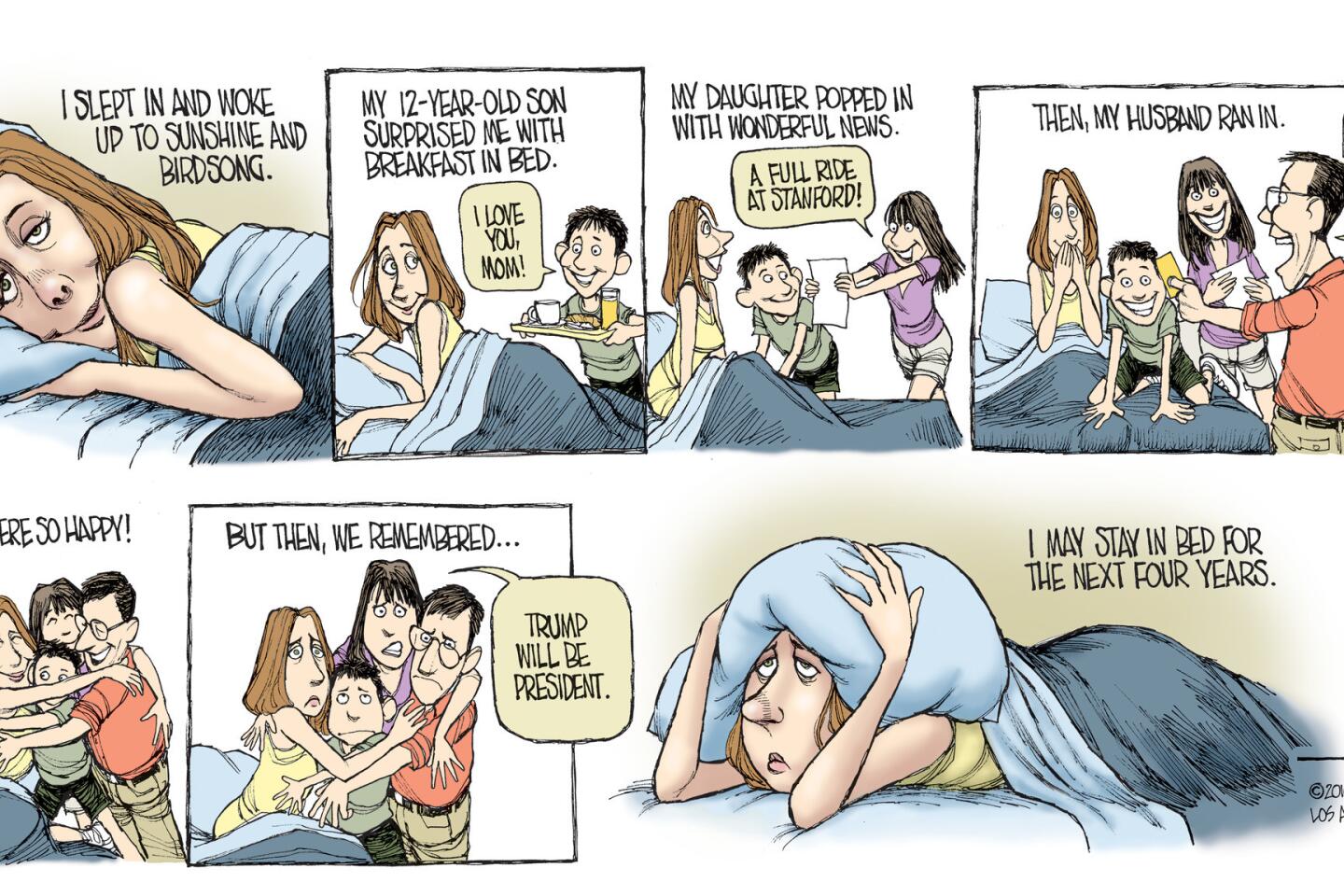

Cartoonists who employ the elephant and donkey as props (and, yes, I do that — sparingly) now too often find themselves in the well-populated camp of journalists who parrot conventional wisdom and, thereby, fail to describe what is really going on. Those who cling to cliches did not recognize until very late the two biggest stories of the presidential primary campaign: the seriousness of Donald Trump’s conquest of the Republican Party and the depth of the Sanders insurgency among Democrats. Those two phenomena did not fit easily into the commonly accepted narrative that said Hillary Clinton was the Democrats’ unanimous favorite and that Republicans always opt for the safe choice.

The parties are no longer the unitary entities they once were. To describe the American political world in 2016, it takes more than elephants and donkeys.

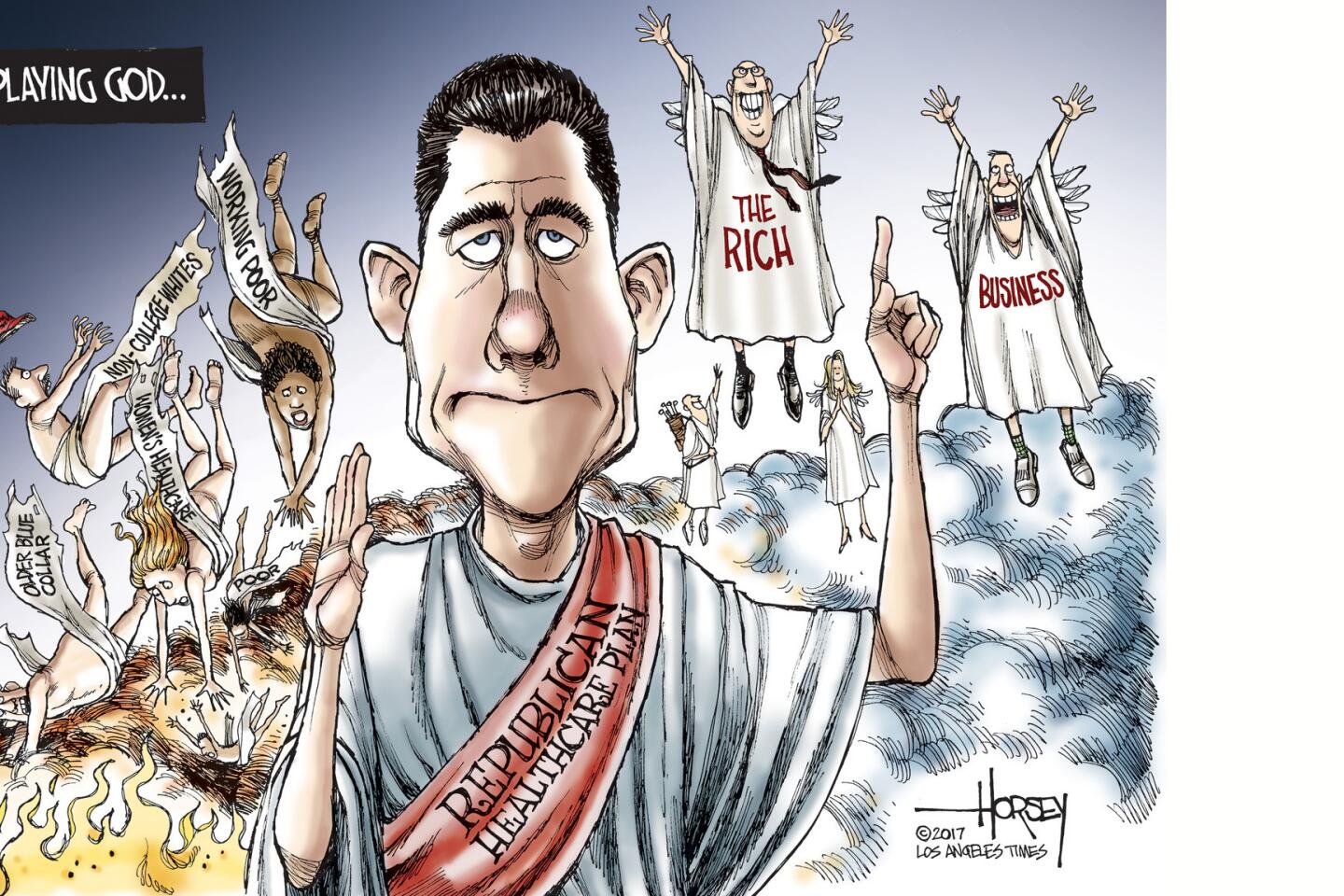

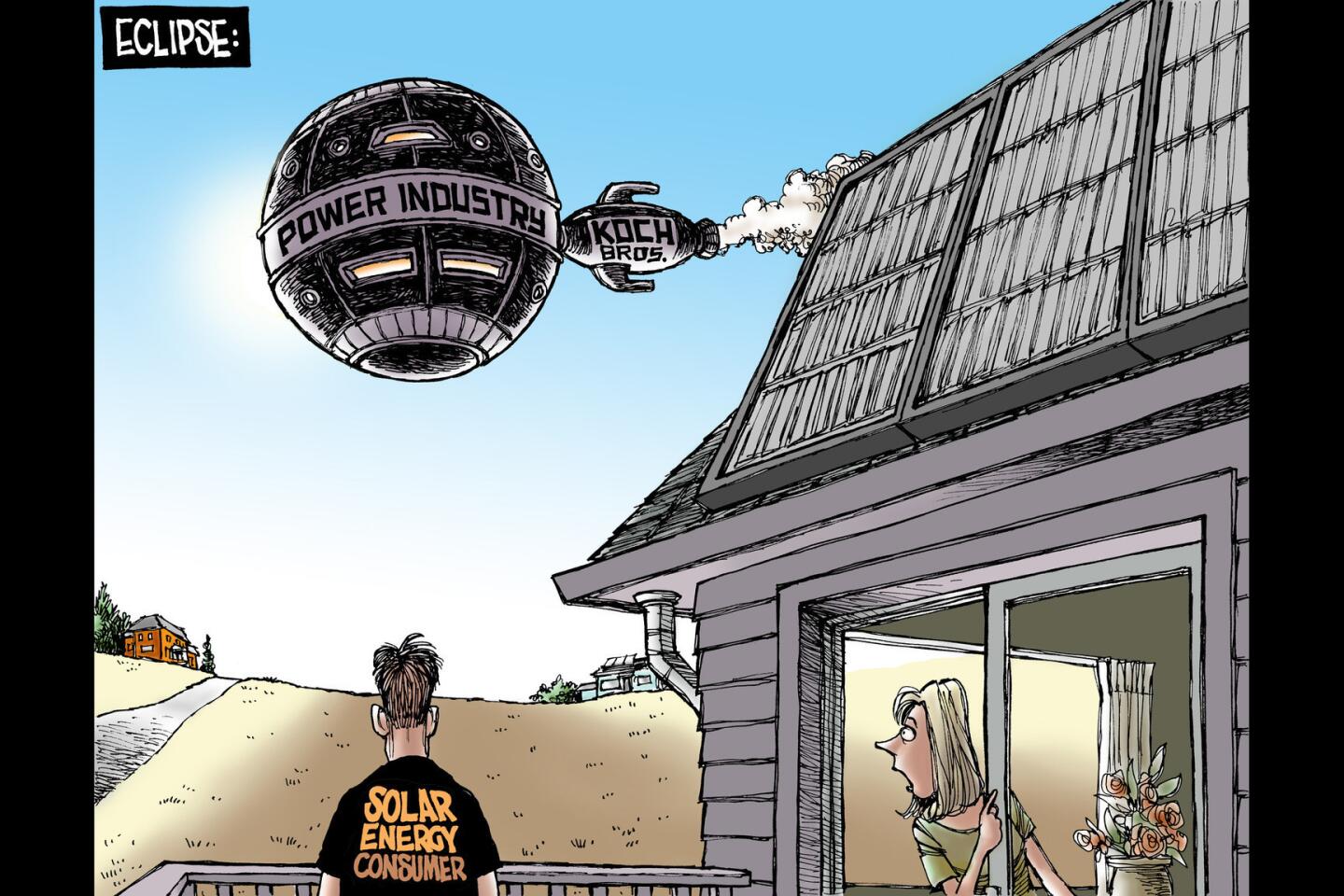

On the left, the primary demarcation line is between traditional liberals, such as Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama and the vast majority of Democratic elected officials, and progressives, such as Elizabeth Warren, Sanders and his young insurgents. For the full picture, though, one must account for the Black Lives Matter movement, environmental activists and the tough-on-defense, global-trade-boosting neo-liberals.

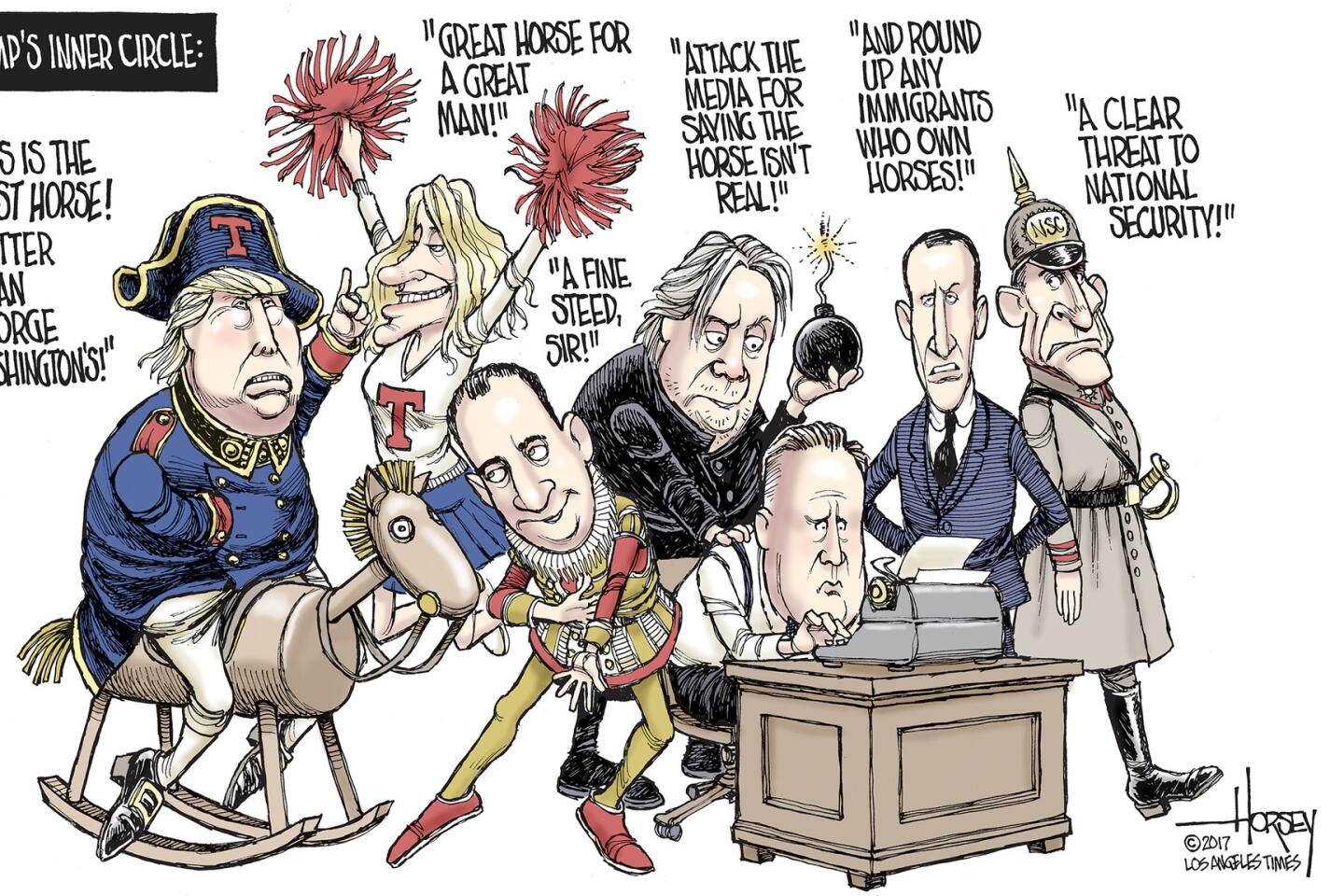

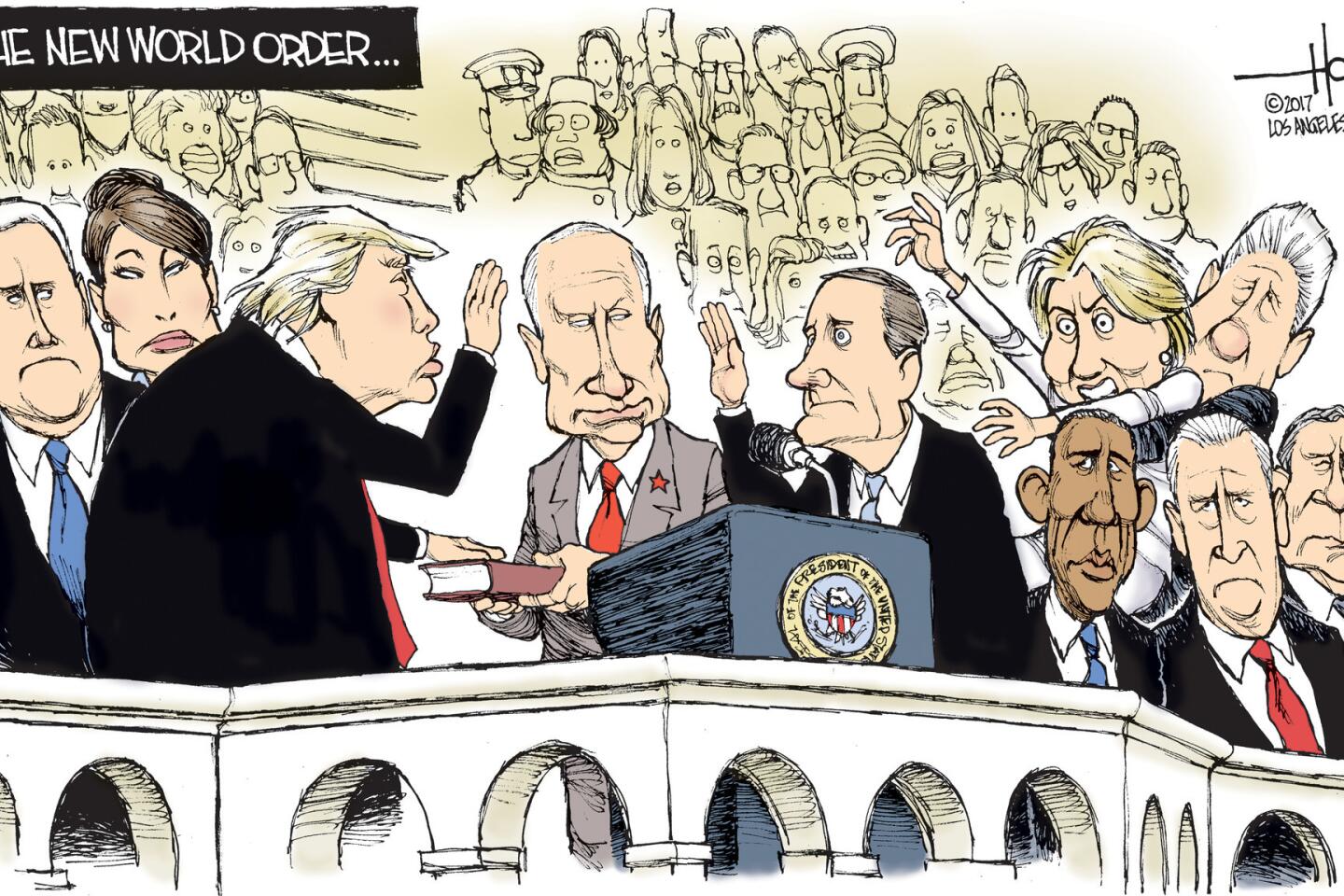

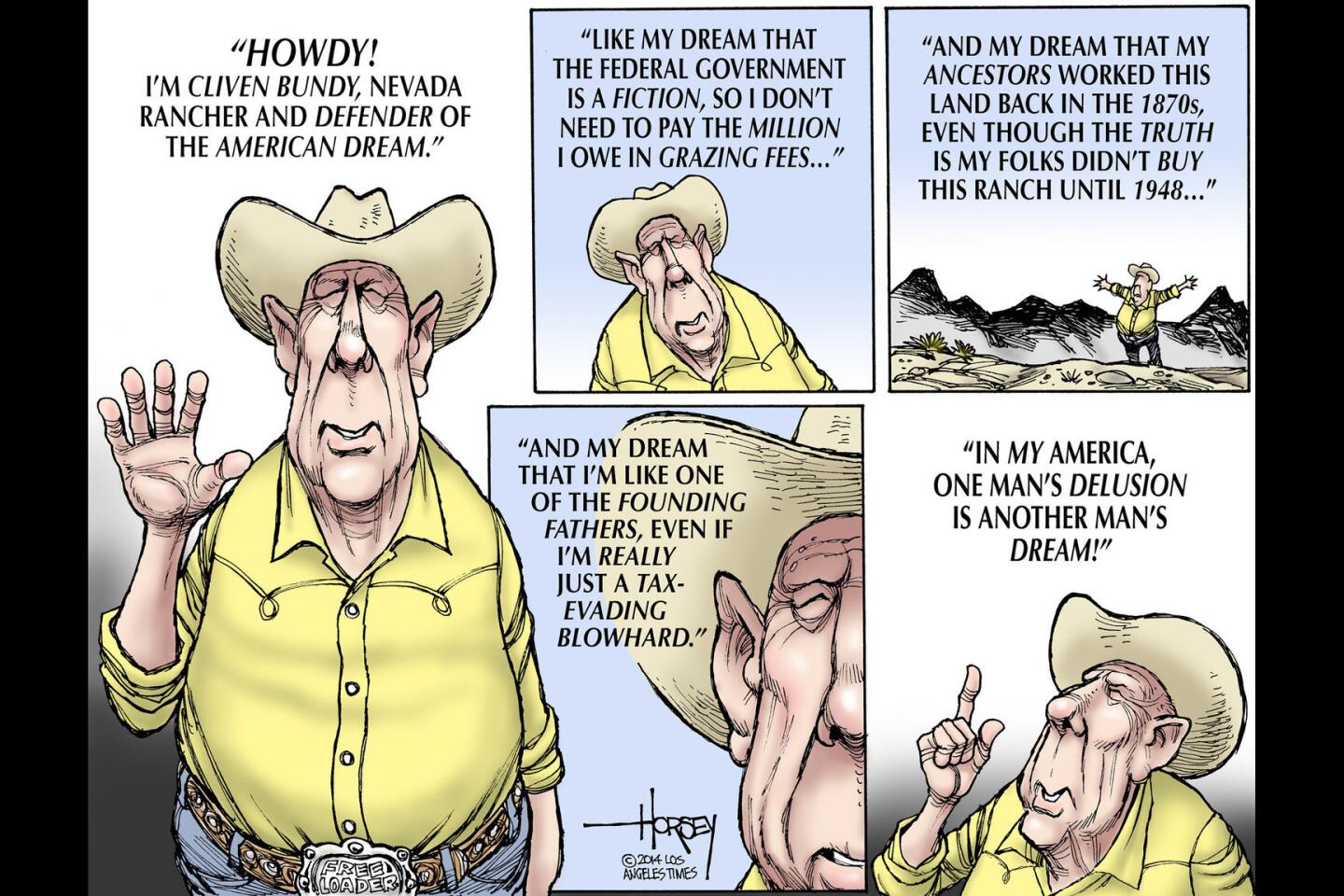

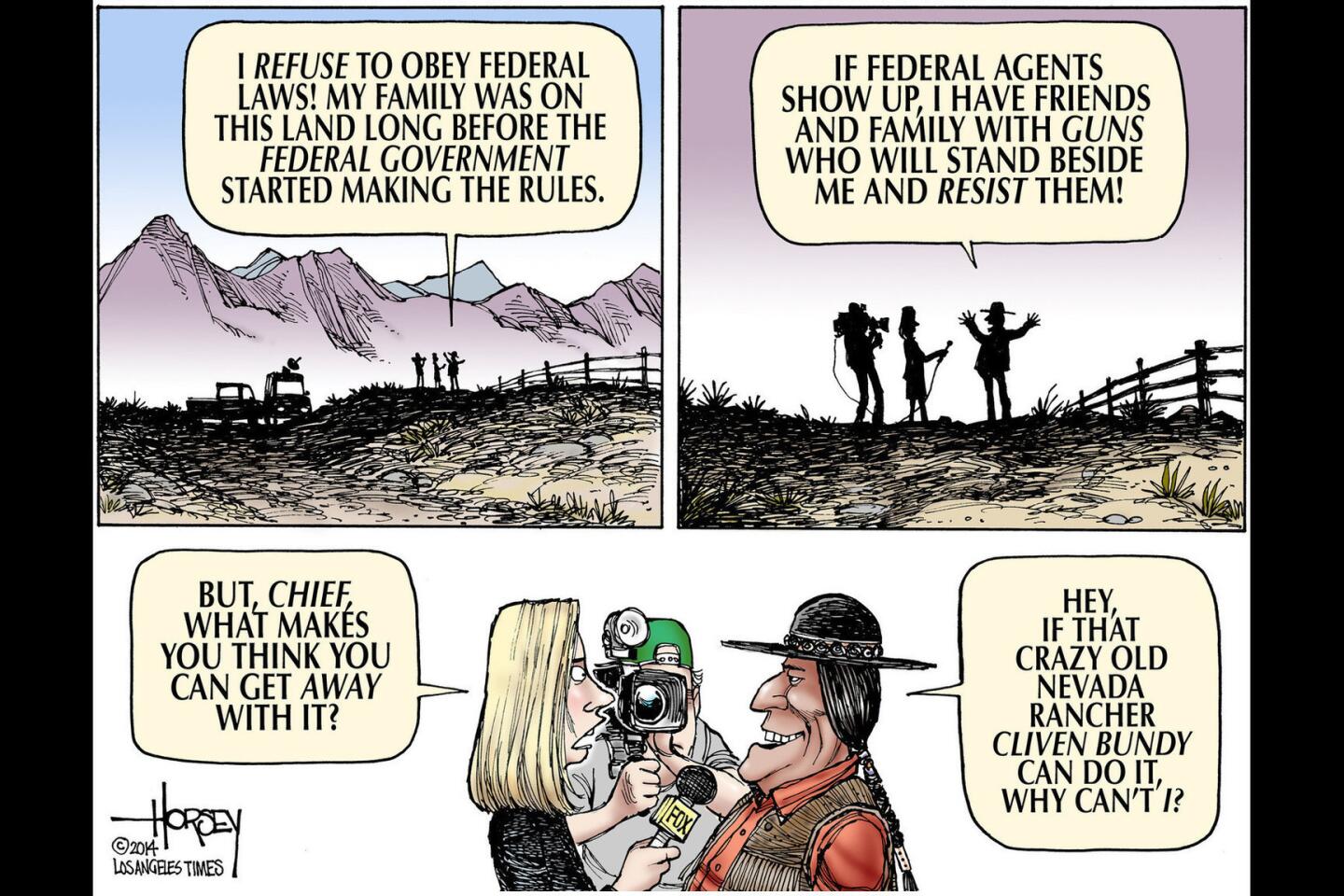

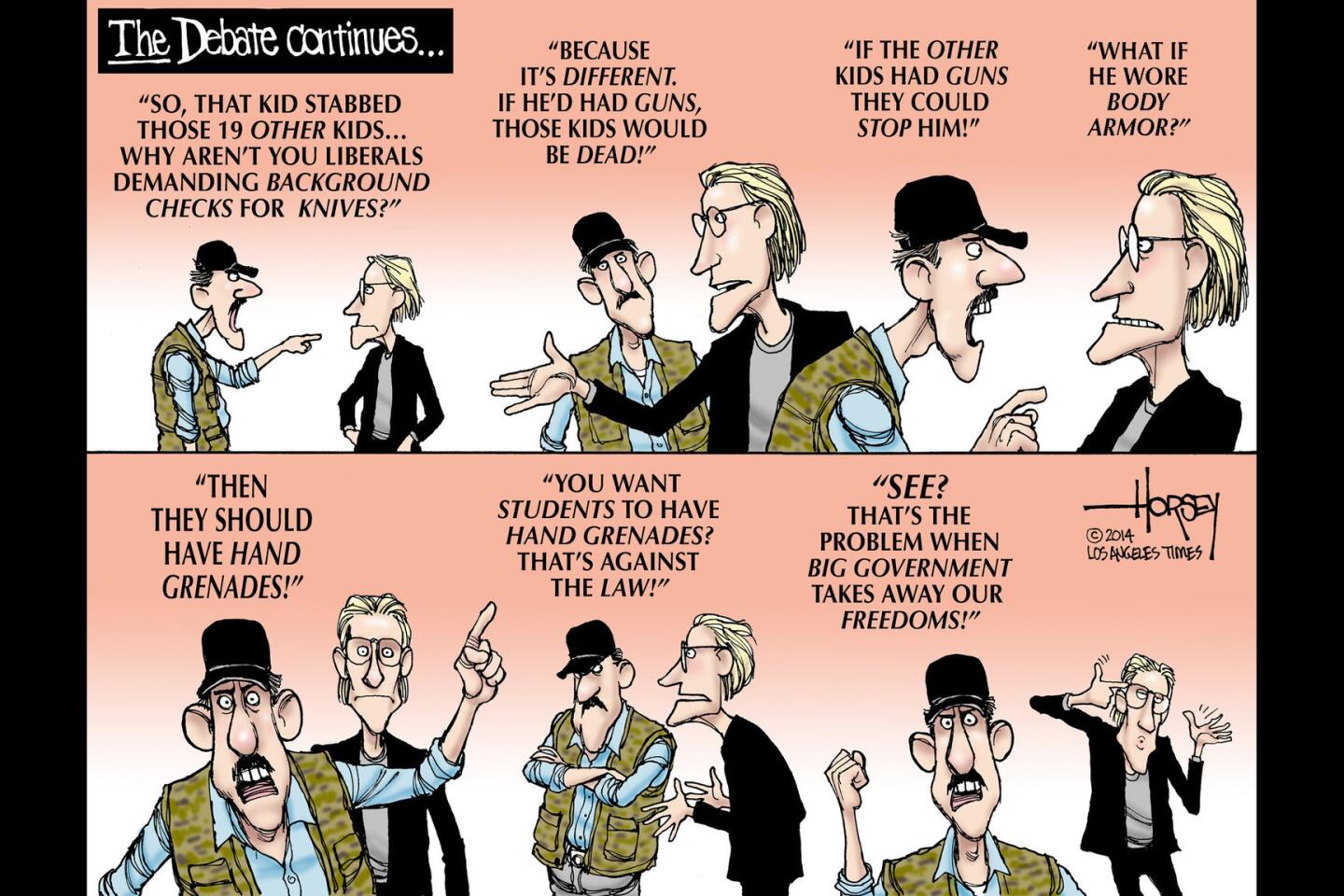

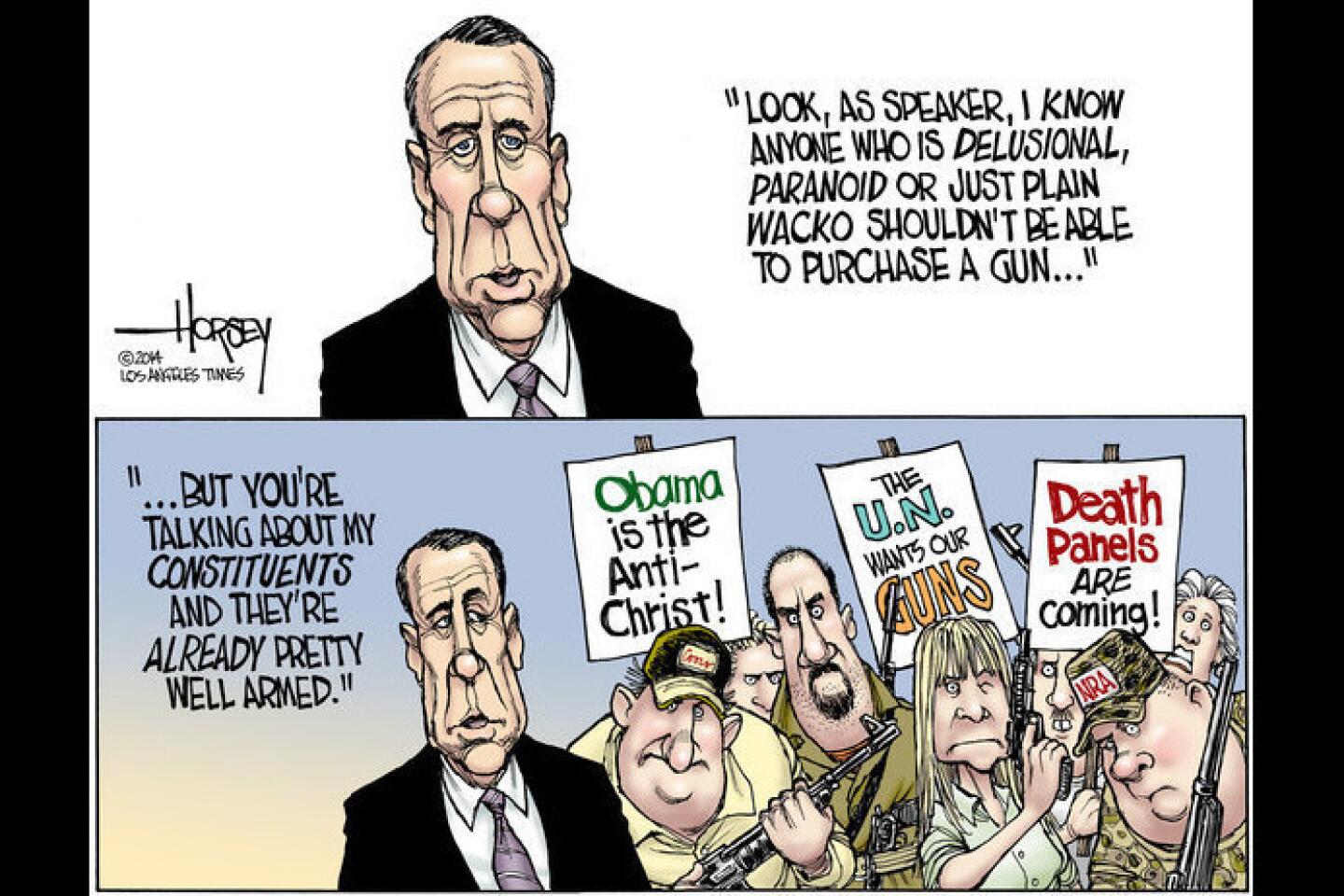

The right is even more fraught and fractured. On the extreme is the Alt Right — the gaggle of anti-establishment, Internet-trolling, hyper-nationalist, immigrant-bashing, white-identity activists who are an embarrassment to mainline Republicans, but who see a kindred soul in Trump. There are the tea party followers, repulsed by any form of taxation and antagonistic to Big Government (as long as no one touches their Medicare and Social Security). There are the libertarians who do not care if you smoke pot, but will shoot you if you do it on their private property. And, there are the right-wing evangelicals who do not worry about the plight of the poor in the manner of Jesus, but who care greatly about fetuses and the private lives of homosexuals.

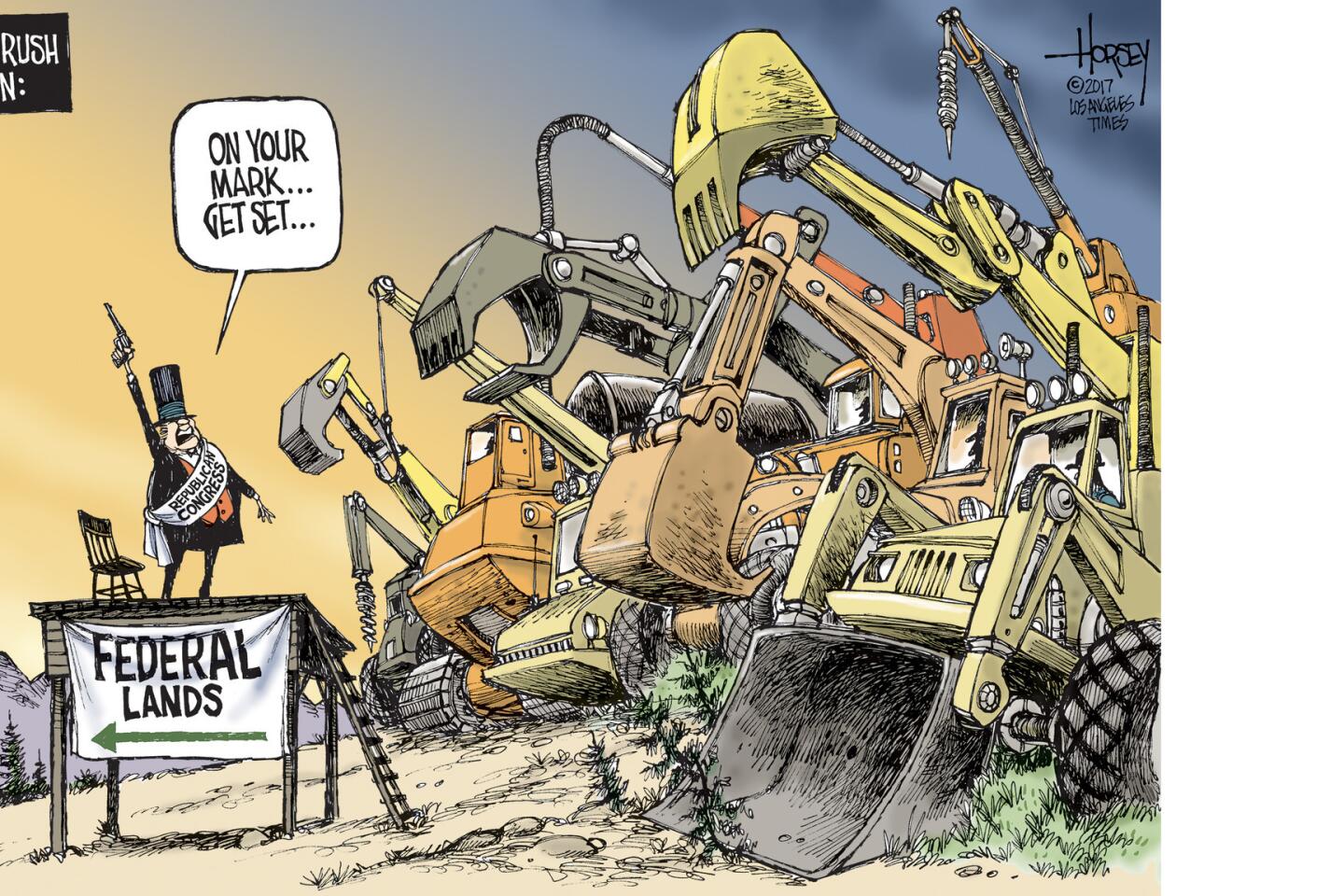

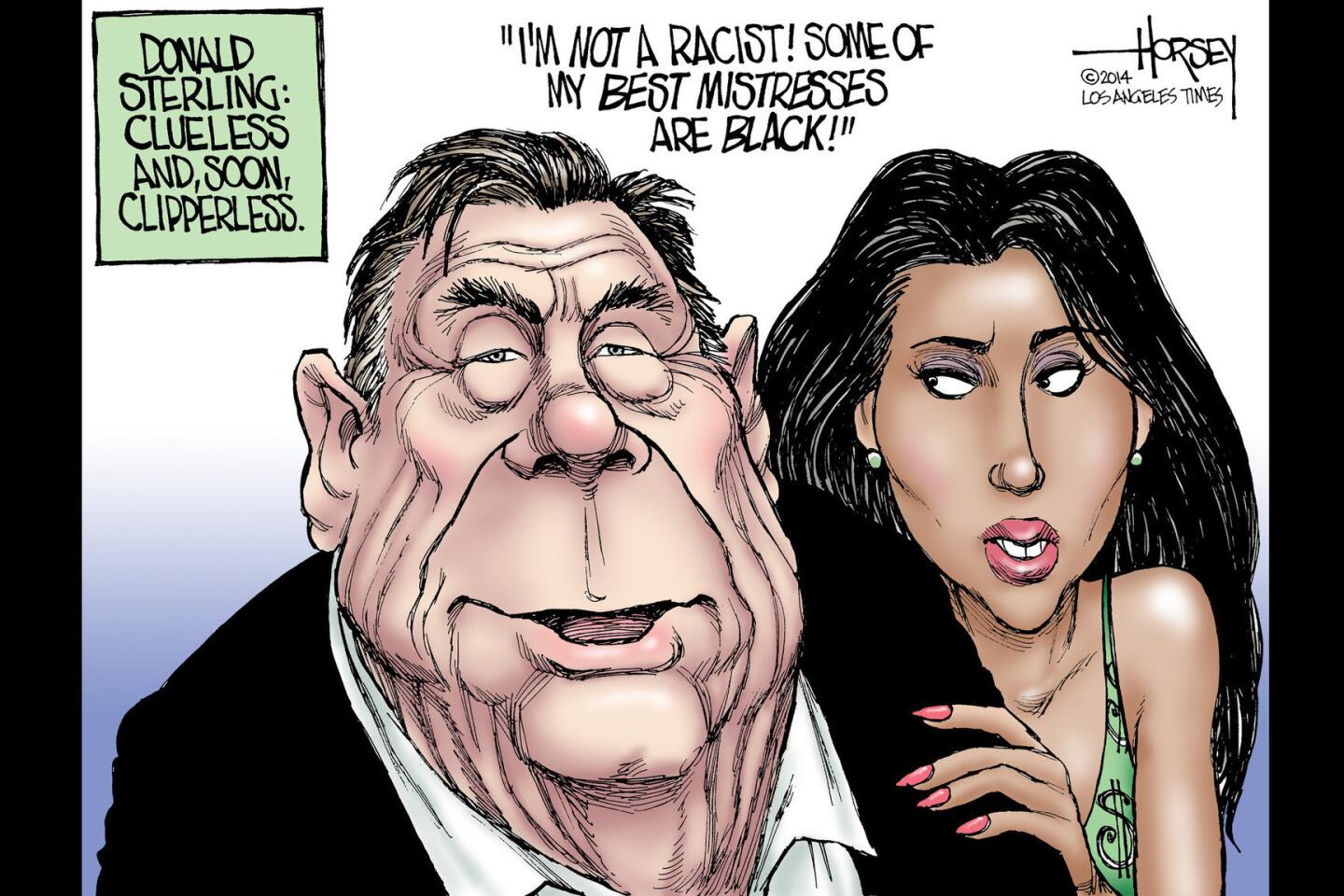

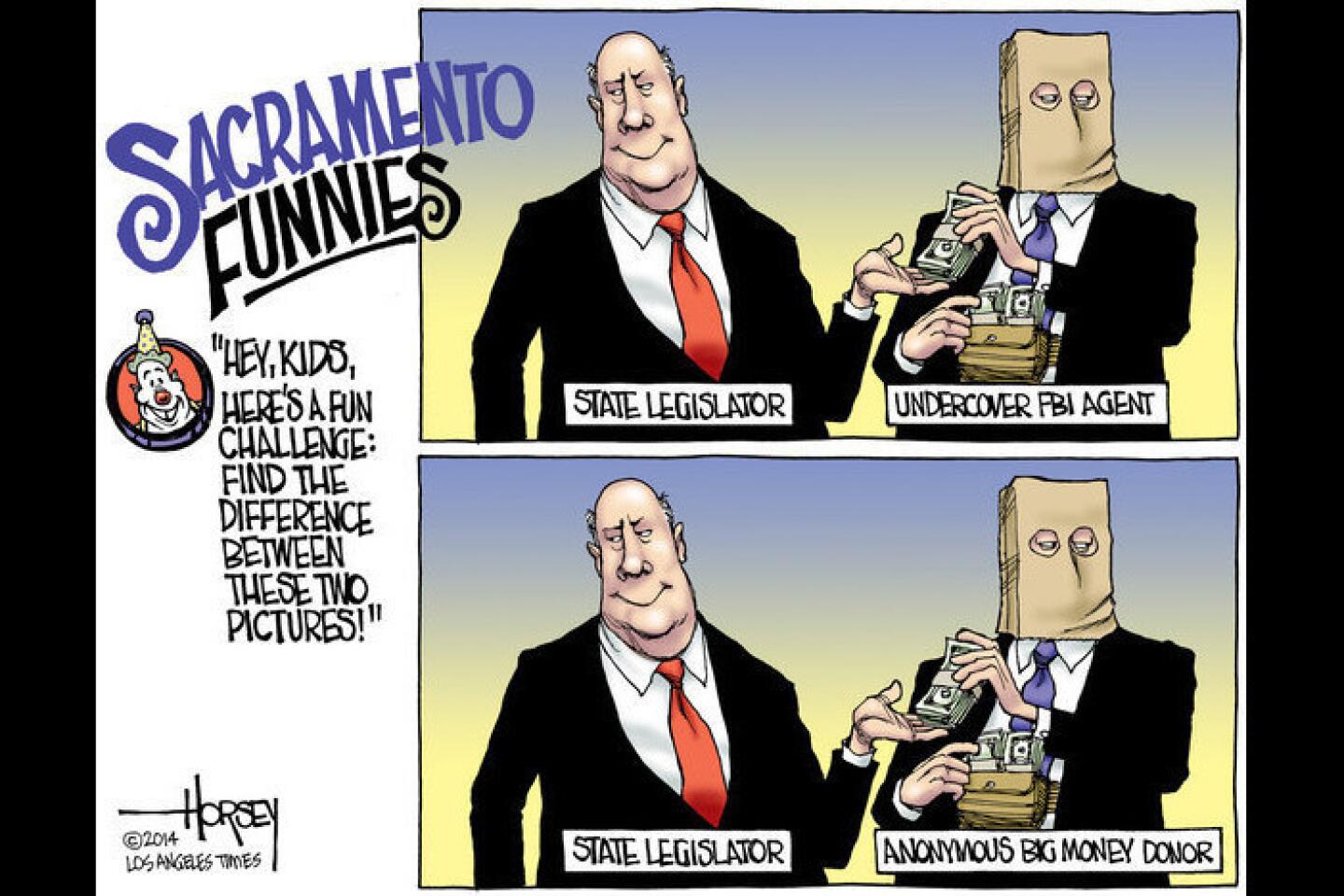

Add to that the big money donors whose main political interest is protecting their own wealth and the Republican elected officials who generally cater to the needs of those donors, mix in the gun rights zealots, the conservative think tanks, a horde of talk radio hosts, Fox News and the hawkish neo-cons, and you end up with an array of “Republicans” who cannot all be encompassed with one symbol — even one as large as an elephant.

Of course, the American political scene has never been quite as clearly defined as cartoons of donkeys and elephants implied. When Nast himself initially latched on to the donkey as a symbol (it had been around since the days when Andrew Jackson’s enemies labeled him a “jackass”), he used it to caricature just one faction of Democrats, the northern “Copperheads.” But, in less riven times, the two animals were a useful shorthand.

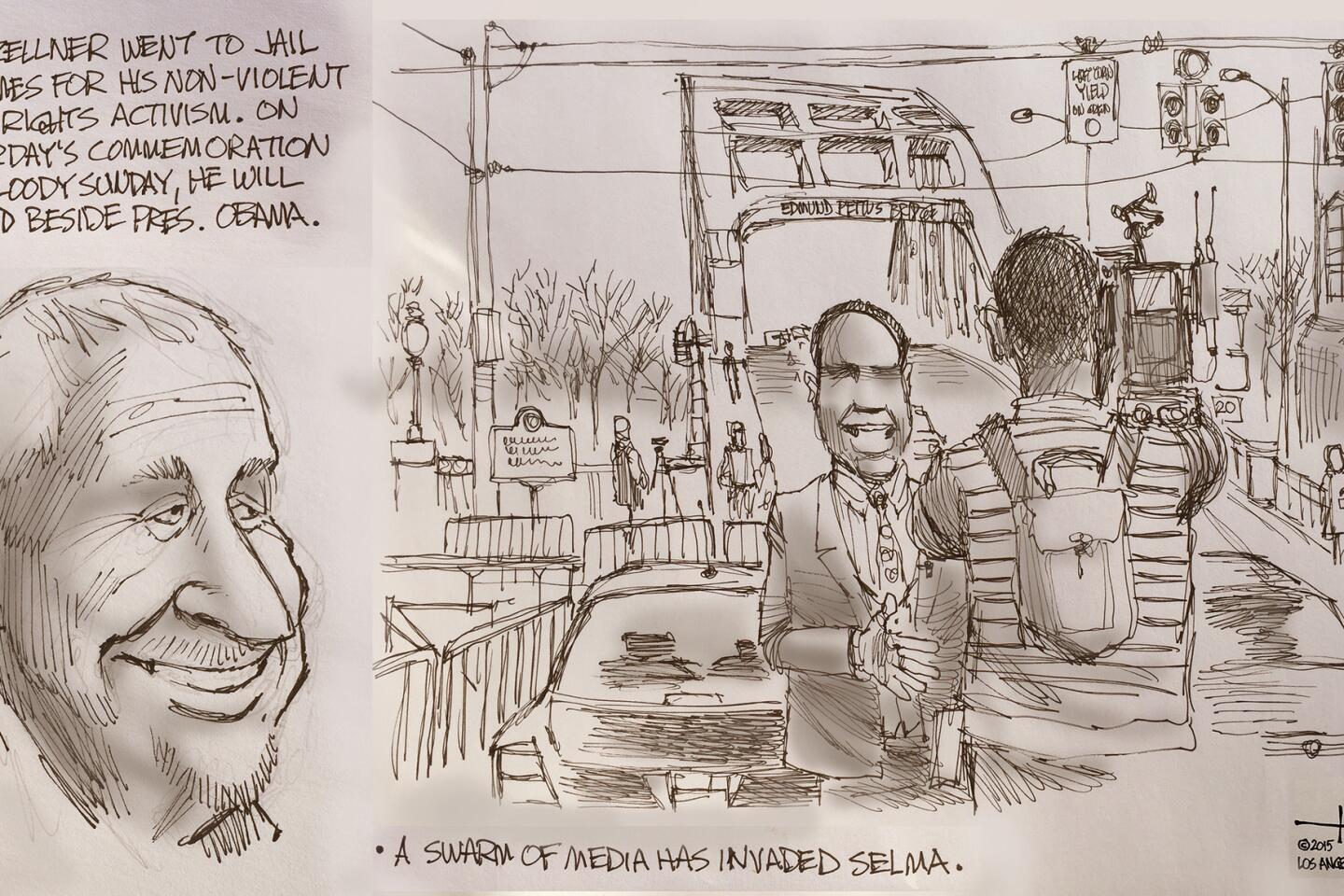

In 2016, though, political cartoonists need an entire menagerie.

Follow me at @davidhorsey on Twitter.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.