An unreliable narrator navigates shifting, shaky ground in a taut riddle of a novel

- Share via

Book Review

An Earthquake Is a Shaking of the Surface of the Earth

By Anna Moschovakis

Soft Skull: 208 pages, $16.95

It you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Anna Moschovakis’ “An Earthquake Is a Shaking of the Surface of the Earth” is my kind of novel: taut and narratively ambiguous, a book of riddles or a riddle of a book.

It takes place in an unnamed city at a moment not unlike the present, narrated by an actress who may be losing her mind. Early on, this unnamed figure recalls her final stage performance, which ended with her breaking character and acknowledging to the audience, “Something is happening that I don’t understand.” Meanwhile, the city in which she lives has been beset by earthquakes, not merely a swarm, or a main jolt followed by a series of aftershocks, but rather an ongoing state of disruption, seismicity as spasmodic “movements that convulse the ground beneath us, that almost never stop, not completely, so that now motion, rather than stillness, has become the rule.”

Or has it? Among the many strange and vivid pleasures of the novel is that we cannot be certain, since as the book progresses, the narrator appears to grow increasingly unstable, although this may be an illusion as well.

Moschovakis is a poet and the author of two previous novels, “Participation” and “Eleanor, or the Rejection of the Progress of Love”; she has translated works by Annie Ernaux, Albert Cossery and Georges Simenon. “An Earthquake Is a Shaking of the Surface of the Earth” is reminiscent of these writers, propulsive and elusive at once.

From “Black Echo” to his latest, “The Waiting,” Michael Connelly’s Harry Bosch books keep taking readers to the dance — partnered with a detective you can’t help but root for, in an L.A. of risks and second chances.

Like Ernaux, Moschovakis’ language is spare and neutral, although such neutrality may be a ruse. Like Cossery, she sets the book in a cityscape that is both recognizable and slightly off, as if rendered from a dream. Like Simenon, there is a murder in these pages, or the desire to commit one, and to reveal this is to give nothing away. From the outset of the novel, the narrator tells us that she means to kill her roommate, Tala, whose arrival is portrayed as a catalyst: “The movements, the shaking, the cracking of the concrete patio,” the narrator observes, “began shortly after she moved in.”

Still, in this moment, perhaps, we also find ourselves in the realm of the imagination, because Tala has disappeared. Did she ever exist? Do the earthquakes? The truth is that it doesn’t matter. What compels us is less the outer world than the narrator’s tangled inner life.

To develop such a sensibility, Moschovakis employs a variety of destabilizing strategies. To begin, there is the novel’s floating cast of secondary characters, including two loosely held friends, J.P. and Celia, and the mysterious barkeep at a neighborhood spot. “Before the ground physically started to shake,” the narrator confides, “I would describe conversations with J.P. in this way: how first you’re just talking, first you’re delighted or bemused, and it goes on, and it goes on and it goes on. And then, the ground you’re standing on starts to move.” Earthquake as emotional disruption, in other words, less a matter of body than of mind. Moschovakis makes this clear from J.P.’s initial appearance in the novel. “It’s going to stop,” he cautions of the shaking, “and you’re going to realize that it never really happened.” That admonition resonates throughout the book.

‘Lazarus Man,’ the ‘Clockers’ author’s first novel in nearly a decade, examines New York through a tenement collapse and its aftermath for a cast of characters.

Even more, the narrator’s displacement emerges in the structure of “An Earthquake Is a Shaking of the Surface of the Earth.” Composed of forms and fragments, it employs a range of typefaces and methods of delivery. Moschovakis augments the central narrative with lists, notebook entries, fliers, a brochure that J.P. delivers — a gathering of runes, of clues, that may or may not add up.

“What if all, or even half, the people in the world weren’t walking around with a headful of language all the time?” the narrator wonders. “What if all, or even half the people I knew weren’t?” The question is less rhetorical than reflective, addressing, as it does, the possibility that the inner life of others “was not reportable the way mine was, because it wasn’t happening in words.”

This may be the essential conundrum of the novel, or maybe “mechanism” is a more appropriate term. “An Earthquake Is a Shaking of the Surface of the Earth” interrogates language as a means of analysis or observation, focusing on its incongruities. “[I]t becomes clear, at the end of every episode of extreme panic, pain, or fear,” Moschovakis writes, “that the opposite of intolerable isn’t tolerable but something more like ecstatic.”

Tom Pyun’s fast-paced ‘Something Close to Nothing’ uses everything from Meryl Streep to hip-hop dance to remind us that gay parents are as impulsive and conflicted as anyone else.

Meanwhile, the narrator seeks meaning wherever she can find it — in the brochure’s pointed questions, for instance, which include “WHAT OR WHO IS HOLDING YOU BACK?” and “HOW WOULD YOU FEEL IF THEY WERE GONE?”

And yet, for her, language remains shifting and ephemeral, difficult to interpret, or to see. Even the brochure blurs to irresolution. “The light made dark shapes on its bright surface, quicksilver abstractions,” the narrator recalls, “which prevented the words from capture. FL_R_LF it seemed to read, in big block type.” Later, after a nap, she feels “behind me for J.P.’s brochure, which I’d left on the side table. There was nothing there.”

The effect is of a profound dislocation, which separates her not only from the world around her but also from herself. “At some point,” she explains, “I lost track of who was asking questions, and who was answering them, of who was leading and who was being led.”

Acclaimed author Charles Baxter takes on America’s absurdities, aided by technology, in his new novel “Blood Test.”

That’s a tricky place for a novel to arrive at, a kind of stasis of the soul. It works, however, because of the depth and movement of the writing, which aspires not to resolution but to immersion, evoking how such dislocation feels. “The voice in my silent mouth,” Moschovakis writes, “was asking, Can we live with this? Can we live with all of this? Can we live?”

These questions apply to every one of us. Where do we find ourselves, after all, but in a world defined by disruption, where earthquakes real or metaphorical and other uncertainties assert themselves at every turn? How do we “[s]nap back. Snap into it. Snap to,” when we are constantly assailed?

“We were alone and not alone,” the narrator insists, “both things true at the same time.” For Moschovakis, then, it is the asking that’s important, since the answers are, as they have ever been, fundamentally unknowable.

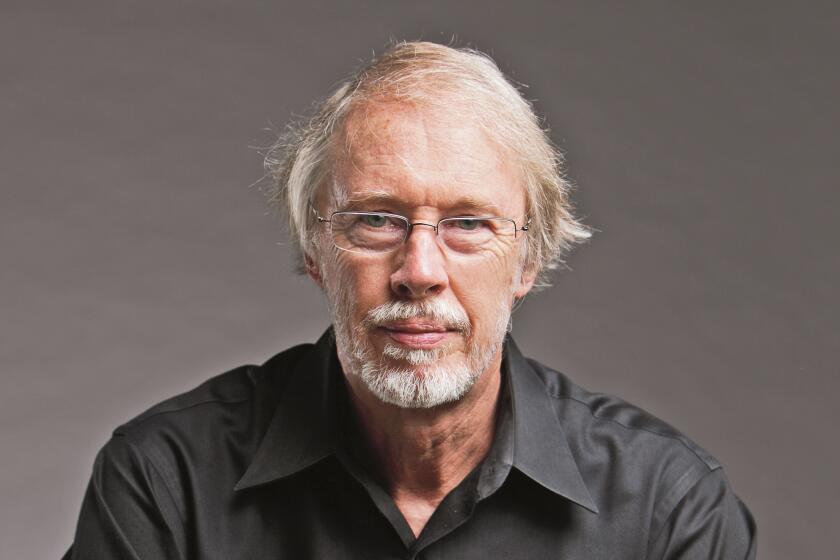

David L. Ulin is a contributing writer to Opinion. He is the former book editor and book critic of The Times.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.