A narrator brings us along as she makes meaning from a traumatic childhood

- Share via

Book Review

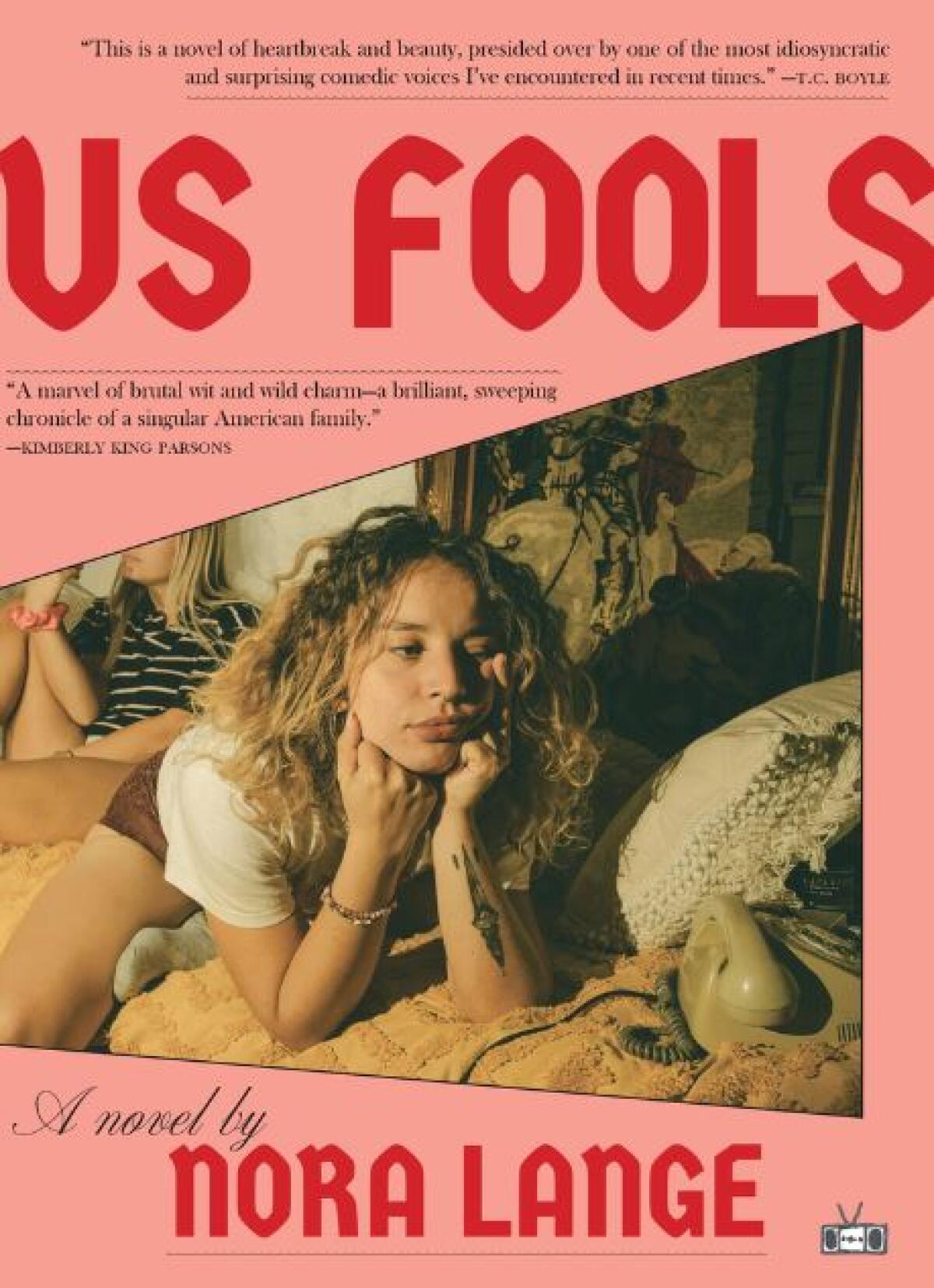

Us Fools

By Nora Lange

Two Dollar Radio: 340 pages, $18.95

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Bernie, the narrator of Nora Lange’s novel, “Us Fools,” grows up on a farm in central Illinois in the late ’70s and early ’80s, but Bernie isn’t as interested in portraying the farm or the landscape as she is in portraying her family, especially her older sister, Joanne, who is smart, rebellious and disabled. According to Bernie, she and Joanne come from a long line of women who had been hard to handle and have lived, in some ways, tragic lives. Lange’s style is complex and comedic, giving “Us Fools” an unusual feel — do I laugh, do I sigh, do I stick it out and try to comprehend what’s happening?

Novels written in the first person can seem a little self-obsessed, but Lange does a good job of investigating how Bernie tries to understand the complexity of her relatives and her relationship to each of them. She begins when Bernie is about to turn 9 and Joanne is 11. Their parents aren’t around, and Joanne decides “to jump from our roof,” which is about 25 feet above the concrete driveway. Bernie doesn’t stop her or run to find the parents. She thinks that Joanne has more to teach her than anyone else, and whatever Joanne wants to do, she can’t be stopped from doing it. Bernie knows already that anything that Joanne does will reveal something new and fascinating to her (maybe to Joanne, too) and she writes about looking at Joanne injured on the driveway: “I relished it, even if I pretended I didn’t.”

Bernie’s parents have plenty of problems to deal with. It’s the late 1980s, and the farm crisis puts everything they depend upon in danger. Bernie is only 7 when their concerns become specific, but she knows that her father, Henry, and her mother, Sylvia, are plenty worried. They know that debt, low prices for production and corporate greed could wreck the life they are used to, and as Bernie gets older, she realizes that her parents, especially her mother, were frantic at the time and didn’t know how to handle the situation.

At one point when Bernie is only 7 years old, her mother tells her, referring to Joanne: “She’s your problem now.” Bernie believes her mother. The rest of the novel is an exploration of how Bernie’s perspectives on Joanne change over time. Bernie tries to help her sister, but also not be like her. As she grows up (she is about 30 when she is organizing her memories) she learns to see the larger picture; one of the phrases Lange has Bernie use to describe herself and her sister is “junk kids.”

But Bernie’s parents are also a mystery to their children. About a third of the way into the novel, Lange writes: “I can remember seeing our parents gnawing at each other and wondering if my sister and I would ever find that kind of love, that stark addiction. Sometimes our parents demanded we go outdoors to eat our dinner or do our chores. ‘That’s what flashlights were for,’ they would say, blissed out and disgusting.”

Unfortunately, Bernie’s detailed obsession with her own feelings creates a problem for the reader: Lange doesn’t try to develop any analysis of how Bernie’s parents came to be the way they are. She settles for attributing Sylvia’s personality disorders to family history, but she doesn’t go into enough detail about the actual history to enable the reader to grasp what Bernie does not.

Lange is interested in how Bernie manages to put together her own life, and as you read, the story becomes more and more compelling. She is extremely aware of her disadvantages and of the way Joanne influences her. The difference between Bernie and Joanne is that Bernie wants things to change, both socially and politically, but she also wants to figure out how to fit in and find some pleasures even if things don’t change. Joanne is a rebel to the core, who always expresses her feelings about their parents, or about where they live, or about what she sees as threats and opportunities no matter how unusual, or, from Bernie’s point of view, cruel, her feelings are.

Lange is a generation younger than I am, and I think that she does an excellent job of depicting how frantic life has seemed for young people in the past 40 years. Can a girl or a teenager deal with it, as Bernie does, or is a young woman wiser to move to the middle of nowhere and escape it, as Joanne does?

The real pleasure of the book, once you get used to it, is the complexity of Lange’s narrative style, the way it replicates the moment-by-moment passage of time in Bernie’s life and portrays how she puts up with the difficulties of learning to understand and survive the hand she has been dealt. Funny, sad, angry, pleased, frightened, resigned — Bernie jumps from one to the other page after page and pulls the reader along with her. For a debut novel, it is quite remarkable.

Jane Smiley is the author of many works of fiction and nonfiction.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.