Opinion: Will a ‘smoke-filled room’ pick Biden’s replacement? History shows the convention system works

- Share via

Now that President Biden has dropped out of the 2024 presidential race and endorsed Vice President Kamala Harris to be the nominee, it will ultimately be up to Democratic National Convention delegates to formally select a new nominee for their party. While many associate the convention system with less-than-impressive nominees, such as the obscure senator Warren G. Harding, the record isn’t that bad. And even Harding managed to win the presidency.

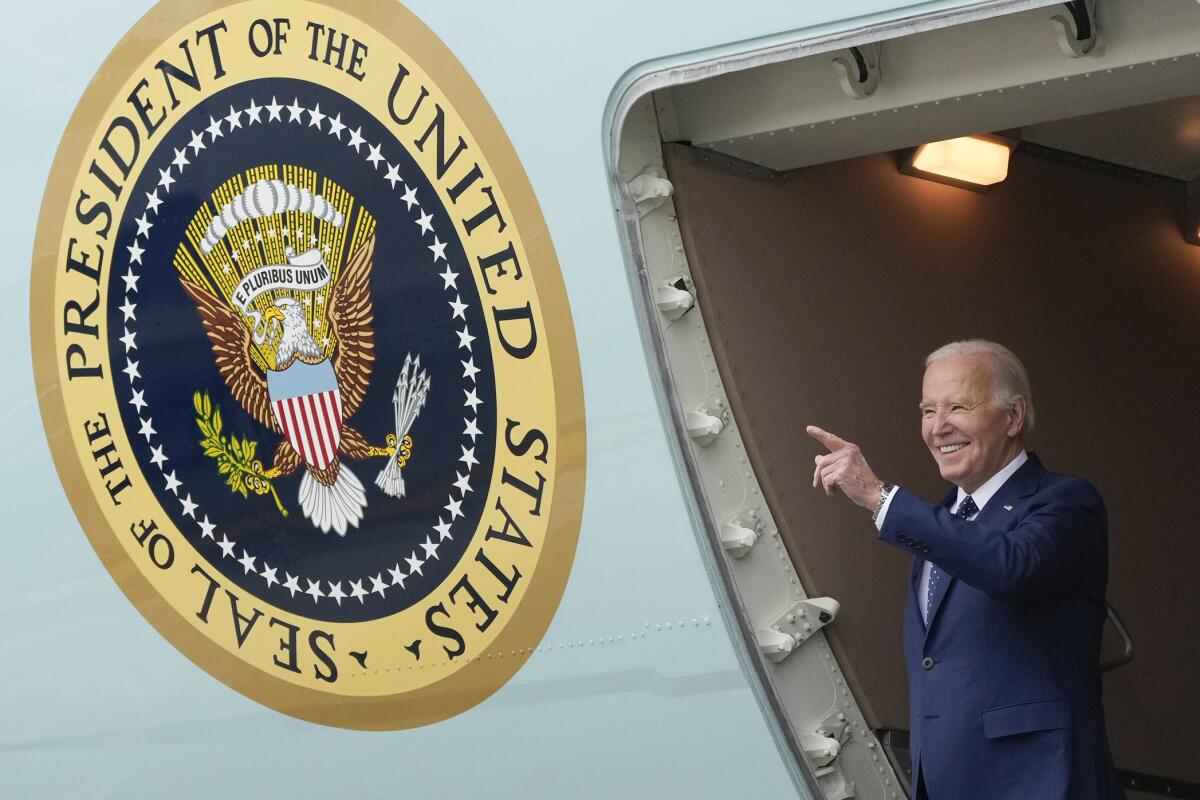

President Biden announces that he will step aside, opening a path for a new Democratic presidential nominee.

The Democrats’ convention next month will mark the first time in more than 50 years that a major party nominee was selected outside of the democratic process of primaries and caucuses. The Republican speaker of the House has already claimed that having the convention replace Biden would be “wrong” and “unlawful.” Others have conjured up the image of the return of the “smoke-filled room,” a term coined in 1920 when Republican Party leaders gathered in secret in Chicago’s Blackstone Hotel and agreed to nominate Harding, a previously undistinguished U.S. senator from Ohio, for the presidency. He went on to be a terrible president.

The tradition of picking a nominee through primaries and caucuses — and not through what is called the “convention system” — is relatively recent. In 1968, after President Lyndon B. Johnson announced he would not run for reelection, his vice president, Hubert Humphrey, was able to secure the Democratic nomination despite not entering any primaries or caucuses. Humphrey won because he had the backing of party leaders such as Chicago Mayor Richard Daley, and these party leaders controlled the vast majority of the delegates.

President Biden’s decision to bow out of the November election leaves a path for Vice President Kamala Harris to replace him that would have seemed unlikely for most of the last three years.

Many Democrats saw this process as fundamentally undemocratic, so the party instituted a series of reforms that opened up the process by requiring delegates to be selected in primaries or caucuses that gave ordinary party members the opportunity to make the choice. The Republican Party quickly followed suit, and since 1972 both parties have nominated candidates in this way.

Some Democrats are worried that a new nominee, selected by the convention, will, like Humphrey, lack legitimacy because she or he will have secured the nomination without direct input from Democratic voters around the country. In response, they’ve suggested what’s being called a “blitz primary” in which Democratic voters would decide on a nominee after a series of televised candidate town halls — a proposal that seems wildly unrealistic. There’s no mechanism for setting up a workable election process in such a short period of time. The convention is where the decision will have to be made.

At the very first convention, held in 1831 by the National Republicans — ancestors of today’s Republican Party — party leaders and insiders nominated Henry Clay for president. Although Clay lost to Andrew Jackson the following year, he is considered one of the greatest politicians of the 19th century.

The convention system in both parties went on to nominate Abraham Lincoln, Ulysses S. Grant, Woodrow Wilson, Franklin D. Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower and John F. Kennedy, all of whom were elected president. Of course, conventions also nominated lesser figures such as Horatio Seymour, Alton Parker and John W. Davis.

But who’s to say that the current system has done any better to produce electable candidates?

Yes, there have been strong candidates such as Ronald Reagan and Barack Obama, but there have also been less successful candidates such as George McGovern as well as weaker presidents including Jimmy Carter and George W. Bush.

Had the old system been in place this year, there’s a chance that the Democrats might have avoided their current predicament. To the extent that Democratic Party leaders were aware of Biden’s decline, they might have been able to ease him out in favor of a better candidate — if they had been in control of the nominating process. In fact, party leaders in previous decades often knew more about the candidates than the public at large ever would learn and could exercise veto power over anyone they thought had serious vulnerabilities.

With Biden’s withdrawal, it remains to be seen if the new Democratic nominee will be a strong candidate or, if elected, a good president. But there’s no reason to think that this year’s unusual path to the nomination will have any effect on those outcomes.

Philip Klinkner is a professor of government at Hamilton College in New York. This article was produced in partnership with The Conversation.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.