An entertaining new novel explores if women working on OnlyFans are victims or savvy capitalists

- Share via

Book Review

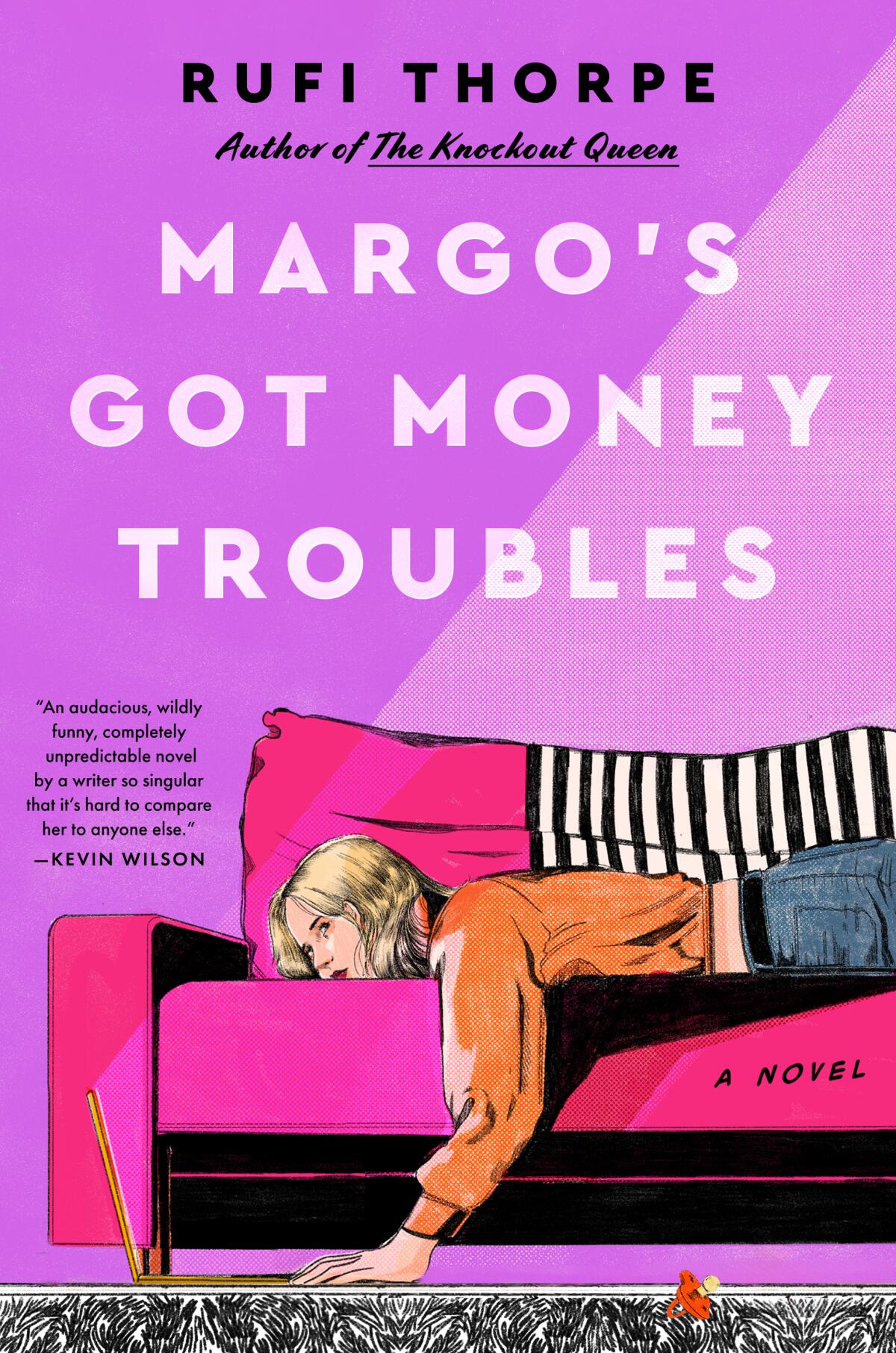

Margo's Got Money Troubles

By Rufi Thorpe

William Morrow: 304 pages, $28

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

Does the publication of “Margo’s Got Money Troubles” mean it’s finally Rufi Thorpe’s moment? Ever since her gripping debut novel “The Girls From Corona Del Mar,” Thorpe has enjoyed a cult following among writers and critics for her fiction grounded in the California landscape. However, despite years of enthusiastic buzz, award nominations and glowing word-of-mouth praise, the general reception for her work has remained subdued.

Now, Thorpe’s literary hum has translated into a resounding roar. Long before publication, the Hollywood Reporter announced that A24 had acquired the rights to the author’s fourth novel, “Margo’s Got Money Troubles,” with David E. Kelley slotted to write the television adaptation as well as Nicole Kidman’s and Elle and Dakota Fanning’s production companies on board to executive produce.

What caught their eyes? I’d argue that beyond Thorpe’s strong characters and tight plots, what sets her apart from her peers is the gnawing philosophical tension that rests at the center of her books. “Margo’s Got Money Troubles” seizes upon the conundrum of the virgin-whore paradigm, using the boom of OnlyFans to explore if the women building followings on the site are pitiable victims or savvy capitalists working the system.

Margo Millet was a 19-year-old student and part-time waitress when she stumbled into an affair with Mark, her English professor at Fullerton College. Their six-week fling wasn’t particularly noteworthy. She reflects that, “He was a wind chime in human form, dangling dorkily from the glorious tree of higher education.” Without the money to attend New York University, alongside her best friend, Becca, Margo found herself untethered, an all too familiar state.

Miranda July’s book ‘All Fours,’ about a Los Angeles woman’s reckoning with perimenopause, imagines the end of fecundity as a joyful second flowering.

She grew up with Shyanne, her single mother, who worked in retail and waited with unfounded hope for Margo’s dad, Jinx, to leave his wife and kids for her. Jinx was a professional wrestler who traveled the world, making it easy to conceal his affairs and breeze in and out of Margo’s life. After drug addiction led to a bout in rehab, he retired from the profession, his marriage dissolving. As Jinx’s life shifts into a new chapter, Margo finds herself unexpectedly pregnant with Mark’s baby.

Reconciling the aftermath of a flashy wrestling career is a fitting crisis for Thorpe’s novel that’s fraught with people who are always something more than they appear to be. Teachers are lying cheaters, wrestlers are performers, and unwed mothers aren’t so easy to pigeonhole. Curiously, it’s in Mark’s classroom that Margo first begins to distinguish the power of perspective and narration. Distinguishing between fictional and real characters, Mark stresses that fictional characters “are only interesting because they aren’t real. The fakeness is where the interest lies.” It’s a kernel of truth that Margo holds onto.

Thorpe latches onto the ideas of perspective and circumstance as well as delusions of fantasy and reality throughout the book. Deploying a structural twist that also helps expand the way we understand her lead character’s experience, Thorpe gives Margo the liberty to shift from first to third person: “It’s true that writing in the third person helps me. It is so much easier to have sympathy for the Margo who existed back then rather than try to explain how and why I did all the things that I did.”

Kaliane Bradley proves imperialism, the scourge of bureaucracy and cross-cultural conflict can be utterly entertaining in ‘The Ministry of Time.’

The grace of sympathy is also largely absent from blanket generalizations regarding women’s sexuality. Frustratingly, it’s Mark who tells his class, “The way you look at something changes what you see.” If only it were so simple. This lack of perspective and sympathy explains why it’s easier for Thorpe’s characters to shape-shift rather than to try to explain themselves to people who fail to acknowledge complexity.

Mark doesn’t practice what he preaches. Adoration sours, and faced with her pregnancy, he ceases all communication. Margo recognizes that “the things Mark liked about me never felt like they really had anything to do with me. They were more his fantasy of me.” In spite of logical arguments (Becca lays it bare: Raising a child “is not a philosophical question. It’s a financial decision.”), Margo decides to go ahead and have the baby.

However, once Bodhi is born, she loses her job as a waitress. Two of her three roommates, understandably, leave for a baby-free apartment. Margo is stuck: Her mother is no help; she’s too busy courting a prudish suitor. And with no available — much less affordable — child care, Margo can’t hold down a job. Reconciling “how sacred the baby was to her, and how mundane and irritating the baby was to others,” Margo found herself “so raw and leaking, so mortal, and yet stronger than she’d ever been.”

Conveniently, in fiction, solutions have a way of presenting themselves once you find your confidence. Rootless Jinx takes up residence as a roommate and unlikely home chef, providing for Margo in a way he never did when she was a child. The question of employment is resolved by what a person might imagine to be one of the easiest opportunities available to a stay-at-home mom: developing a following of clients on OnlyFans. Anxious about what it means to participate in consensual and voyeuristic but entirely virtual sex work, Margo’s roommate Suzie points out: “It seems weird to say a celibate person is a slut. Like, you’re just pretending words have meaning at that point.” With that, and the financial independence the site provides, Margo gives herself over to the work.

The bawdy, playful way that Margo constructs and flaunts her online persona, Hungry Ghost, is a total lark. At each step, she remains in control of her image and engagement. Lest you think that Thorpe has opted to shower Margo’s work with the cliché of empowerment, think again. The work is depicted without phony glamour, but also without the taint of shame. Margo’s gift for language and penchant for the absurd flourishes as she distinguishes herself from other women on the site.

The work becomes a puzzle of professional networking and optimization, aided by Jinx, who sets his protective, paternal hesitations aside when he sees that OnlyFans isn’t too far removed from WWE. Together, they forge new friendships and create an unlikely family for baby Bodhi. In what feels like a fairy tale twist, Margo finds an unlikely kinship with a client who pays her for endearing personal stories rather than provocative photographs or videos. Complications arise and the antics halt when outside forces raise realistic and harrowing stakes. Thorpe allows her characters to remain flawed but bent toward redemption in this wholly entertaining, utterly endearing and thought-provoking novel that asks, “What kind of truth would require this many lies to tell?”

Thorpe’s novels defy easy categorization. Her characters’ radiant energy and her books’ knotted plots don’t align with the moody atmosphere and tone poem quality of most contemporary literary fiction. Yet, these novels remain more intense and rigorous than most upmarket women’s fiction. It’s exhilarating to find an author who wants to tell you a good yarn, but also ask a lot of complicated questions. While she’s been deemed a beach read, perhaps because of her California roots, Thorpe deserves to break past the limited vision that marketing places on female writers.

Lauren LeBlanc is a board member of the National Book Critics Circle.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.