Opinion: How L.A. can stop excluding Latin American Indigenous language speakers

- Share via

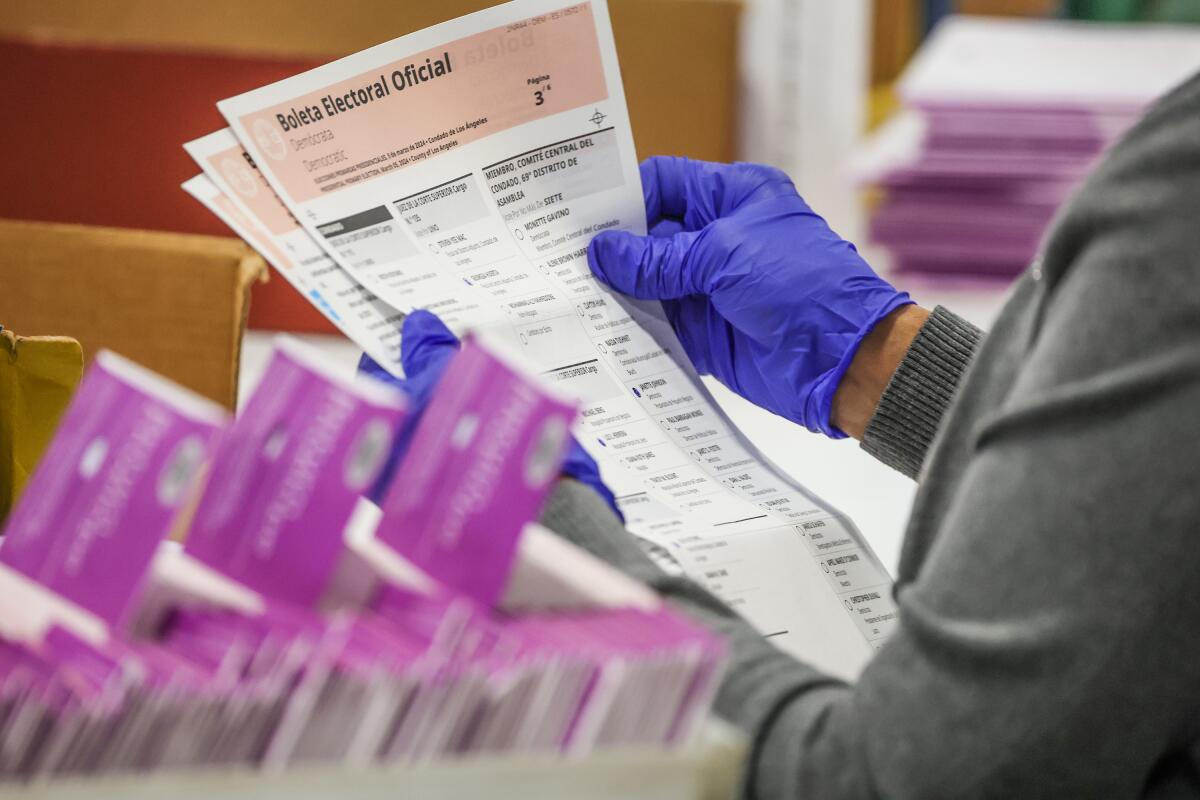

When Angelenos voted in this year’s California primary, an important group was left out: speakers of Latin American Indigenous languages such as Zapotec and K’iche’, which are not among the 19 languages in which L.A. County provides voting materials. It’s a particularly concerning oversight in Los Angeles. Our city has the largest population of Native American and Indigenous peoples of any city in the United States — and their omission has serious implications for inclusion.

Section 203 of the federal Voting Rights Act requires that counties provide election materials in the language of a linguistic minority that isn’t proficient enough in English to vote without help. That group either has to be greater than 10,000 people or represent at least 5% of a county’s total population of eligible voters. California also requires tailored ballots, at a lower threshold than federal law does: Counties here have to translate the ballot for any single language minority lacking English proficiency if it makes up at least 3% of a precinct’s voting-age residents.

A change in the way the government asks about race and ethnicity for those who identify as Latino or Hispanic means more accurate date for us all.

To determine compliance with these laws, local and federal authorities look to census data collected every 10 years. But the government has long struggled to provide an accurate count for Latin American people.

Until this year, when the federal government changed the policy after years of debate, the census asked respondents two different questions about whether they were of Latino/Hispanic origin and what their race and ethnicity was. This approach confused some Americans who see their Latino or Hispanic identity as their ethnicity, not distinct from it. The move to combine those questions follows another change that aimed to make the count more accurate: Since 2020, the census has included free-response lines so that people could write in a specific origin, such as German or Nigerian, and counted up to six different origins per respondent, matching those to the broader racial categories such as white and Black.

Allowing those detailed responses seemed to make the data collection more comprehensive, increasing the recorded Latin American Indigenous population by 390.4% from 2010 to 2020. Even so, many scholars, us included, expect that the census still woefully undercounts the population of Central and South American Indigenous peoples.

For speakers of some of the most commonly spoken native languages like Quechua, Nahuatl or Guarani, the conversation is less about whether you speak Spanish but rather how Indigenous languages are left out of the discussion.

More specifically, because it tracks language in much less detail than it does race and ethnicity, it falls short as reliable data for translations. Consider: Although census data documents 22,024 people of Latin American descent in Los Angeles County who speak a language other than English or Spanish — surpassing the Section 203 threshold of 10,000 voters — it does not identify what those languages are.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the nonprofit organization Comunidades Indígenas en Liderazgo (Indigenous Communities in Leadership), or CIELO, collected that missing data. It surveyed Latin American Indigenous communities in Los Angeles and created a map of their language diversity, which shows a concentration of voting-age Zapotec speakers in the Pico-Union and Koreatown areas.

When we overlaid the CIELO map onto a Los Angeles County precinct map, we identified approximately 36 precincts, generally between Wilshire and West Washington boulevards and from South Fairfax Avenue to South Hoover Street, with high concentrations of Zapotec speakers. Our data suggest that these speakers made up more than 12% of adults in those precincts, far exceeding the state requirement of 3%. But because this level of detail isn’t captured by official census figures, these Angelenos can’t vote in their primary language.

The impact of this gap extends well beyond voting. For example, Indigenous people from Mexico and Guatemala lacked essential COVID-19 information in their native languages during the pandemic, prompting CIELO and other groups to provide translations. Similarly, during wildfire seasons, translated information on evacuation areas, shelters and air quality has been scarce. While additional nonprofit groups such as the Mixteco/Indígena Community Organizing Project have stepped up to offer translations, the patchwork reliance on volunteers cannot guarantee access for everyone who needs these resources.

As we near the conclusion of the design phase for the 2030 census, we urge the Census Bureau to actively collaborate with Latin American Indigenous stakeholders to ensure a precise count and capture linguistic diversity within these communities. These collaborations should make sure that respondents understand the updates to the census and are equipped to provide accurate answers. They should also explore avenues to collect more detailed language information. By making sure that every voice is heard and accounted for, we build a more inclusive democracy that reflects the rich diversity of our city.

Jessica Cobian is a senior fellow and Sebastian Cazares is a graduate fellow at the UCLA Voting Rights Project. Heidy Melchor is the founder and alumni advisor of the UCLA Grupo Estudiantil Oaxaqueño.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.