Opinion: It’s been 25 years since Columbine. This is what we’re still getting wrong about school shootings

- Share via

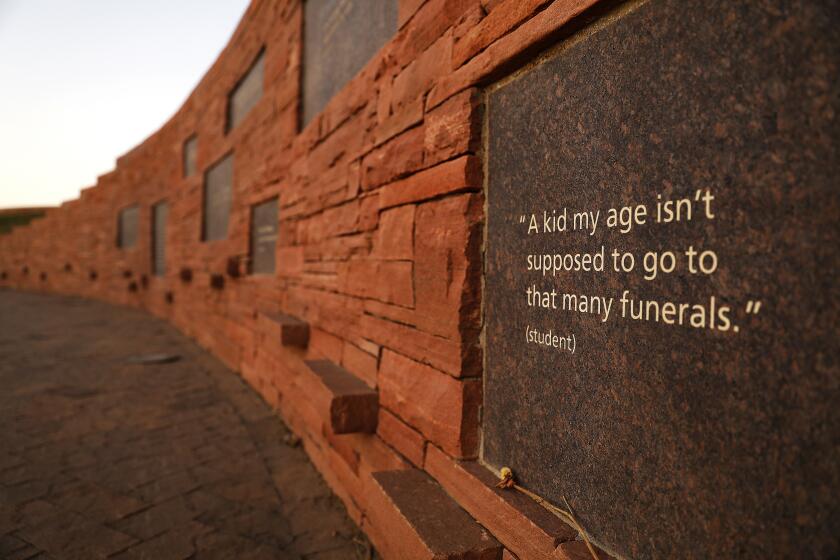

Twenty-five years ago on April 20, 1999, one teacher and 12 students were shot and killed by two seniors at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colo. Another 21 members of the Columbine school community were injured in this shooting and countless lives devastated. That kind of mass violence — and in a school no less — was unthinkable at the time. Yet the past quarter-century has tragically and frustratingly shown that we have failed to keep schoolchildren safe.

The communities of Newtown, Conn., Parkland, Fla., and Uvalde, Texas, like Littleton, were subsequently forced to contend with the unimaginable. And so too have hundreds of others that have not made the national news despite gun violence in their schools.

Data from the Washington Post allow us to estimate that more than 370,000 K-12 students have been exposed to firearm violence since Columbine. And data my colleagues and I are gathering show that there have been nearly 350 intentional school shootings in K-12 public schools since 2015, meaning these events have taken place during school hours and with a perpetrator’s intent to harm someone else. Firearms are now the leading cause of death among all children and teens in the U.S. and for nearly 20 years prior were the leading cause of death among Black children, reflecting significant disparities that have recently gotten worse.

Our country has mass shootings almost daily. I wish I could tell you after your incident that it will all be OK soon. But that would be a lie.

Indeed, 25 years after Columbine — alongside the rise of school shootings and the corresponding rise of a multibillion dollar school security industry — it is the anticipation of firearm violence that overwhelmingly shapes many aspects of a school, including its safety policies, disciplinary strategies, physical layout and budget. Research estimates that $14.5 billion per year is now spent on school resource officers and security guards. And various states have pushed for structural changes such as installing physical barriers around school grounds, implementing bulletproof windows and increasing the use of metal detectors as ways to safeguard campuses. But there is no evidence these efforts work. Moreover, they often take resources away from the kinds of investments children and schools would actually benefit from.

Instead of investing in the meaningful prevention of shootings, schools have been organized around the inevitability of this kind of violence. An increasing number of districts are arming their teachers with firearms, despite the lack of evidence guiding the effectiveness of such policies. Lockdown drills are now ubiquitous in schools across the U.S., and 1 in 4 teachers reported that their school experienced a firearm-related lockdown within the past year.

School shootings shouldn’t be an inevitability, yet schools are forced to treat them like they are. As research has shown, ready access to firearms increases the likelihood of intentional shootings on school grounds. There is also a rigorous evidence base that provides clear guidance as to which specific policy measures could significantly reduce acts of firearm violence in schools: bans on large-capacity magazines, the implementation of safe storage and child access prevention laws and extreme risk protection orders, among others. But over the past 25 years there have been limited efforts by elected officials to implement the policies that we know would have a meaningful effect.

So many children are dying in school shootings because the U.S. doesn’t focus on prevention. There are ways we can stop these horrific massacres.

Encouragingly, and following more than two decades of no federal funding for research on gun violence prevention, Congress is now helping finance this rapidly growing field that is actively contributing additional solutions and insights. New research is highlighting the promise of anonymous reporting systems that allow students to privately provide tips about potential gun violence, as well as the effects of gun-free school zones. It is also showing how school and community investments in public libraries, bystander interventions and universal school-based violence prevention programs, among others, together contribute to safer schools. This groundswell of new science is providing guidance for policymakers to help scale solutions that work.

There is undoubtedly much still to be done. And the best research can only accomplish so much without significant gun safety legislation. But 25 years after Columbine, it’s clear that our nation can do better. Just as the U.S. is making significant strides to “end cancer as we know it” and has set the goal for motor vehicle road deaths at zero, a goal must be established for the country to eradicate school shootings. In another 25 years, and hopefully sooner, schools should be spaces free from firearm violence, where all children can thrive.

Sonali Rajan is a professor at Teachers College, Columbia University and the inaugural president of the Research Society for the Prevention of Firearm-Related Harms.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.