Opinion: California wants to make your healthcare less expensive

- Share via

Californians have racked up billions of dollars in medical debt. Two years ago, Gov. Gavin Newsom and the Legislature granted authority to a new agency, the Office of Health Care Affordability, to rein in health costs that were racing ahead of residents’ ability to pay. But this effort is in danger of being watered down before it can benefit them.

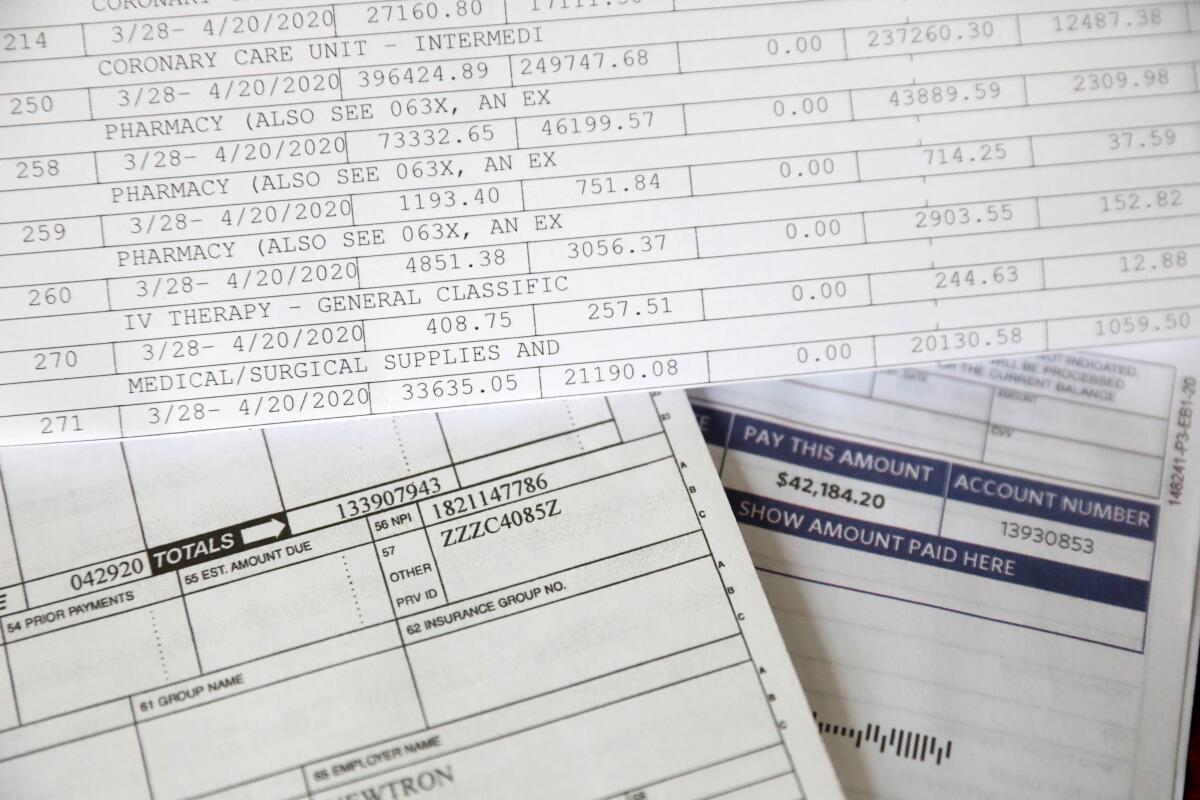

This month, the Office of Health Care Affordability proposed limiting healthcare spending growth to no more than the projected growth in household income — 3% per year over the next five years. For comparison, the median household income in California has grown by an average of 3.5% since 2013, while healthcare spending in the state over the same period grew by an average of 5.5%.

Patients are fed up with shocking bills they didn’t expect and can’t afford. It’s dangerous when Americans conclude: ‘Don’t trust the system.’

The agency will take public comments until March 11 and plans to announce a final healthcare spending cap on June 1. If the state’s hospital and doctor associations have their way, it will look very different in the end.

I study healthcare markets, but California families don’t need a professor to tell them health costs can be ruinous. Last year, the California Health Care Foundation found that more than half the state’s residents had skipped or postponed some type of healthcare in the previous 12 months due to cost.

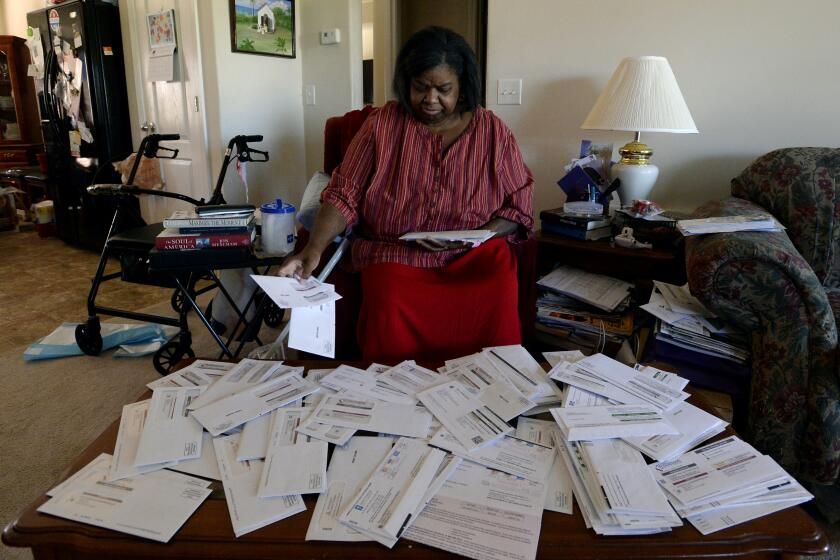

Many who did seek care incurred costs they could not afford. Thirty-eight percent of Californians and over half of those with low incomes report having medical debt. A 2023 study found that medical debt contributed to 41% of personal bankruptcies in the U.S.

California Assembly Speaker Robert Rivas says he likes the idea of a state-run single-payer healthcare system, but isn’t convinced the state can afford it.

Healthcare providers seem to feel that all this economic pain is unfortunate but not their fault. They contend that if California caps spending increases to 3% per year, it will reduce services, increase waiting times and discourage referrals. They argue that the Office of Health Care Affordability is too willing to sacrifice access and quality in the name of limiting cost.

Healthcare providers would rather see any spending cap be based on their costs of providing services. But that would effectively reward providers for higher costs and California residents would be subject to continued unsustainable growth in healthcare spending. A cap linked to household income fairly enforces affordability and puts pressure on providers to limit excess costs that unfairly burden residents with high premiums and deductibles.

An estimated 100 million Americans have medical debt, and 18% say they will never be able to pay off what they owe.

Most economists prefer to rely on competition and market forces to determine supply and demand for services. It is clear, however, that California’s healthcare system is not subject to the competitive forces needed to ensure that it functions as a normal marketplace.

California is not alone in trying to restrain health spending through regulation. Eight other states — Connecticut, Delaware, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island and Washington — have established cost-growth benchmarks. One lesson emerging from these states is that greater transparency about how the new system works and benefits residents will encourage participation. California can learn from this as it implements its cap.

The public comment period for the state’s proposed spending cap provides an opportunity to ensure that policymakers hear from everyone and not just special interests. The Office of Health Care Affordability needs the engagement and support of California’s healthcare consumers to ensure that as policies evolve, they achieve the goal of aligning spending growth with economic growth and residents’ ability to pay. Motivated by a state mandate, California’s providers are fully capable of responding to the challenge.

Glenn Melnick is a professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.