Opinion: Why I built my own tribe for Hanukkah

- Share via

Twenty years ago, I moved from L.A. to San Francisco and then Bellingham, Wash. — so far north I could spit across the border and a Canadian would apologize for being too close. For the longest time I regretted the move from areas with strong synagogues and significant Jewish populations to a town with so few Jews and one synagogue. It was as if I were living up to my genetic destiny as a Jew wandering the desert, but this time with more rain.

Last Hanukkah, I decided I’d had enough moping. Even if I couldn’t find a critical mass of Jews here in the Pacific Northwest, I could cobble together friends who felt Jewish to me. And now, with antisemitism spiking in the U.S., I am all the more motivated to be surrounded by my tribe.

Truth be told, I initially found my friends up north confusing. I’d assumed when I met them they were official Members of the Tribe, a tongue-in-cheek way to describe fellow Jews. Take Vicki, for example, a woman I’d met in a local Buddhist meditation group over Zoom. Vicki’s accent reminded me of the pastrami-on-rye waiters at Canter’s Deli in Fairfax.

Roman Jewish cuisine is unlike any other in the world, with a centuries-long passion for frying. The fritter frenzy peaks at Hanukkah.

“Bliss, man,” she said once, “sometimes you just have to pull the plank out of your butt.”

Vicki’s brassiness drew me to her here in the Pacific Northwest, where niceness comes in all flavors of vanilla. When I found out she wasn’t an official Member, I was surprised. Being around her was a cream cheese schmear with lox on a poppyseed bagel.

Another friend, Janet, a nurse during the Vietnam War, is active in her church. Yet every year she lights a menorah. When I moved to town Janet was drawn to me like chicken to soup, asking for help: “Please show me what to say and how to do this right.”

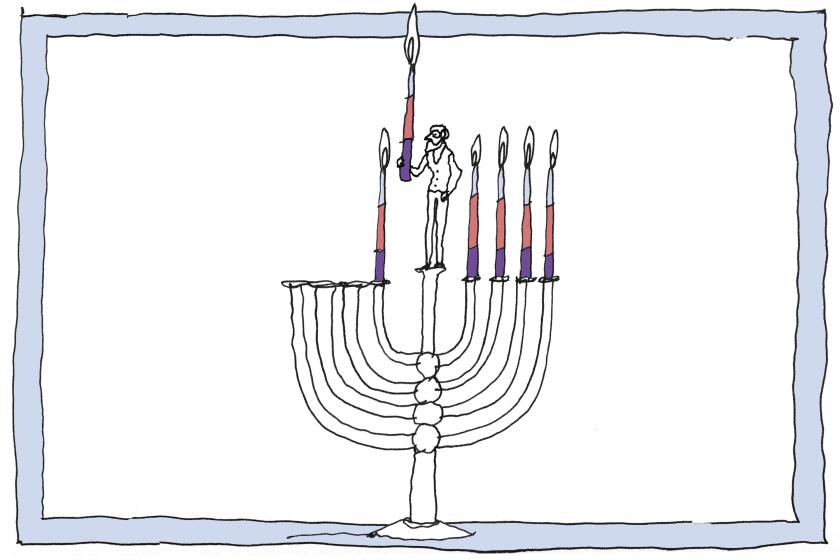

When I showed up at her home the first night of Hanukkah, Janet had already placed all nine candles into her menorah. As gently as I could, I explained that Jews only place two candles in the menorah on the first night: one on the far right to be lit and a second, helper candle — the one that lights all the rest — called the shamash.

Janet returned seven candles into the box. As I held the shamash to the lone survivor, chanting Hebrew, Janet swayed by my side.

I met more and more people who said to me, often in whispered tones, that they’d always felt Jewish. What an odd place for them to gather, here in homogeneous upstate Washington, where you have to really seek out diversity. It was almost as if they were called here.

Thinking of our family friend, the candle-maker “Mr. Hanukkah,” reminds me of the holiday’s larger meaning.

One by one, the need to know consumed all of them. Many of them found out they were 1% to 25% Jewish.

“I’m one percent!” texted one of them.

“One percent what?” I texted back.

“Ashkenazi Jewish.”

“Mazel tov!” I replied. As it was getting close to Hanukkah, I added a few dreidel emojis.

It takes 10 Jews to form a minyan, or prayer group. In the end I pieced together enough of these subcutaneous Jews to form my own minyan of friendship. I felt connected to the legend of the Prague rabbi who created a man made of clay, called a golem, to protect the Jewish people. I created a tribe of my own to protect my heart from feeling so lonely.

Sometimes that protection is literal, as in 2020 when the Proud Boys marched into our sister city 20 minutes away. It was Chuck who showed up to stand vigil as they marched through town. His ancestry test didn’t reveal any Jewish connection, but his actions did.

Christmas, Hanukkah and other holidays tend to revolve around family. But they also provide an opportunity to form relationships with those who live nearby.

Other times, that protection is based on threats that are existential and overwhelming, as when Jews are gruesomely killed in Israel and the reverberations are felt all the way to the U.S. Another non-Jewish friend, Steven, asked how I was doing. I told him I’d heard about a mother in Chicago ushering her yarmulke-wearing son into the car while a group stood at the edge of their lawn staring at them with dead eyes.

He said, “If you need to be hidden, we’ll hide you in our basement.”

Steven stated this with such sincerity, such care, that I felt a lump in my throat. When Jews spin the dreidel at Hanukkah, we play with a pile of foil-covered chocolate coins called gelt. After he made this vow of protection, our eyes met, and I thought about how rich I am in gentile gelt.

I believe that few people are 100% anything, and if someone feels they are Jewish, or stands up for the Jewish people, they have the right to an honorary six-pointed star. I was brought up in a Jewish household and attended religious school, yet my 23 and Me results revealed that I am only 88% — not 100% — Jewish. But I feel Jewish through and through, especially this Hanukkah.

This year on the last night of Hanukkah I will think of nine of my “Jewish” friends. As I ignite each individual wick, and its candle sparks to life, his or her face will flare in my mind. It is a good thing not to be alone at the holidays, regardless of which holiday you are celebrating or who you are celebrating with.

And I will be celebrating with my tribe.

Bliss Goldstein is working on her Jewish magic realism novel, “The Sixth Soul.” She can be found at blissgoldstein.com.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.