Editorial: What we flush down the toilet matters. Only the ‘three Ps,’ please

- Share via

What goes in the toilet, and what goes in the trash? It’s the kind of discussion one has with a 2-year old, and is all the more delightful because it’s a topic generally regarded as taboo in polite conversation. You get to say things such as only “the three Ps” — pee, poop and paper — go in the toilet. Everything else goes in the trash can. Right?

Alas, modern human life is much more complicated and the conversation far more difficult, though fundamentally important for health, safety and good manners. The last century has given us three new Ps to contend with: plastics, PFAS, and pharmaceuticals. We should not flush these, though throwing them in the trash doesn’t mean they won’t come back to harm us.

Microplastics are found in human blood. PFAS — per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, which are known popularly as “forever chemicals” and are associated with a host of bad health effects — taint the drinking water of numerous communities. Drugs meant to treat deadly disease in human beings end up causing illness in other creatures when, discarded, they leach into the water.

State and local authorities must do more to ensure drinking water is free of PFAS, which are found in many household products, including cookware and cosmetics.

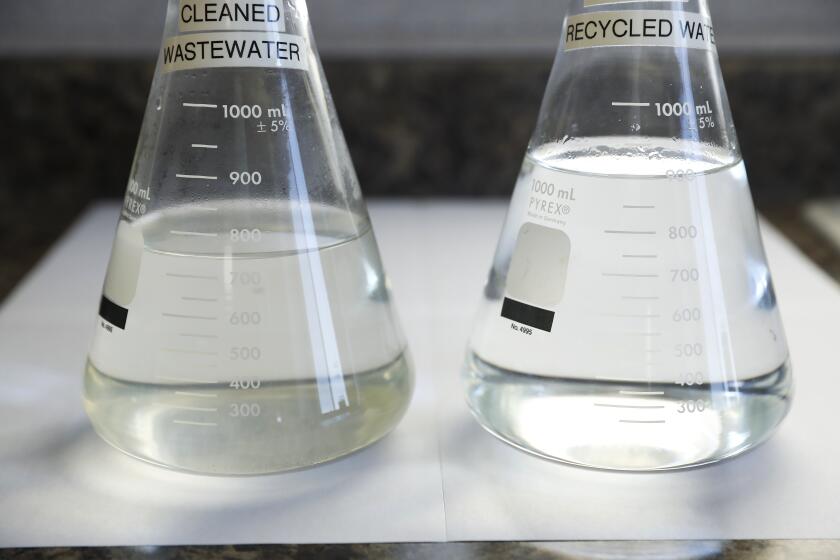

California is currently hammering out regulations that will govern the operation of a new generation of water purification and recycling technologies, and those systems will be major steps forward for health and safety. Water that for too long has been dismissed as merely part of the waste stream, to be flushed into the ocean and supposedly never seen again, will be cleansed and monitored at a level not previously attained to form a buffer against drought. That makes it more important than ever to revisit our approach to managing the three Ps and understand where it may fall short.

The first two — the ones that pass out of the human body — are treated to kill pathogens. Liquids and solids are separated and, to oversimplify a bit, liquids go to the ocean and solids are used to enrich farm soil.

Editorial: Your clothes are polluting the environment with microplastics. Can washing machines help?

Most clothing is made with synthetic, or plastic, materials. When they shed, they add to the scourge of microplastic. Washing machine filters may help.

Human waste fertilizes crops? Yes. Anyone who has bought a bag of Milorganite fertilizer to spread on their lawn and keep it green has in some sense become a customer of the Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, which produces the product from carefully treated biosolids, the word used to describe human — well, you know.

Los Angeles was once dotted with “sewage farms” fertilized, disturbingly, with untreated waste, according to “Brown Acres,” Anna Sklar’s fascinating 2008 history of the L.A. sewer system. They produced vegetables that were considered safe to eat only if cooked. Now L.A.’s waste is properly treated, after which much of it is trucked to farmland in Kern County alongside Interstate 5. Crops there are lush and healthy. Adjacent, unsupplemented land looks like a moonscape.

Every drop of drinking water once passed through someone’s (or something’s) body. The point is to purify the stuff we drink no matter the source, rather than to seek never-defiled fantasy water.

The third P is more problematic. Toilet paper is made to dissolve, but there are arguments and lawsuits over some other products labeled “flushable” (baby wipes and moistened cleaning pads, for example) that municipal sanitation agencies say clog sewer systems and cost taxpayers and ratepayers millions of dollars each year to clear.

Should so-called flushables go into the trash instead? Yes. Municipalities have long lists of things people commonly flush but shouldn’t, including facial tissues, tampons, dental floss and indeed any non-organic material.

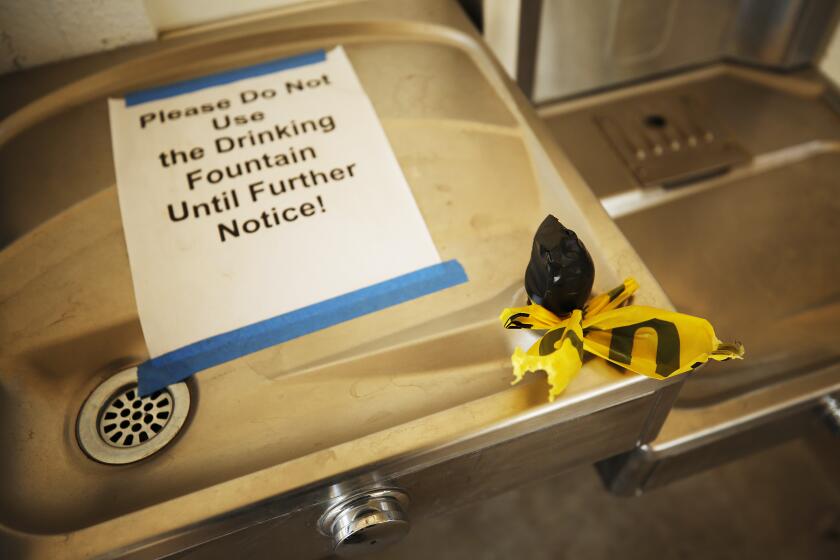

Children in many California schools may to exposed to lead in water fountains unless school districts conduct widespread testing and, if needed, clean up.

But don’t think placing them in the trash renders them harmless. Plastics (like dental floss) in landfills become microplastics that leach any chemicals they were treated with right back into the water. Unused pills are bad news whether flushed or tossed. PFAS leach from some types of paper plates, takeout containers and other things that generally are placed in the blue recycle bin but shouldn’t be.

Some used clothes, old carpets, in fact anything that “miraculously” resists stains, moisture or wrinkling, may leach PFAS. They obviously can’t be flushed but really shouldn’t go into the bin either — not the green one, the blue one or the black one. Many people put them there anyway.

The companies that produce these wonder products make them appear affordable because they “externalize” their costs — they offload them, unseen, onto our sewer bills; our medical bills; our bodies; the land, water and air. How to properly reallocate and recoup the costs of dealing with things that we’re not supposed to flush or toss — but often do anyway — is one of the challenges of the 21st century.

One of the solutions to this conundrum are so-called extended producer responsibility laws, in which manufacturers are forced to assume liability for the end life of their products. California has passed a number of such laws including the Paint Stewardship Program and Senate Bill 54, the sweeping plastic packaging reduction bill passed last year.

The basic rule remains sound: Flush only the three Ps. For now, everything else has to go into the trash, though we need to recognize the hazards that filling our landfills continues to cause and move quickly to a more sustainable system.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.