Opinion: Three words you won’t hear from today’s Supreme Court justices

- Share via

I’ll never forget the moment during my clerkship at the Supreme Court when I realized something about it was deeply broken.

It was April 2014, and I had just pulled an all-nighter to finish a second, 50-page bench memo in a pending case. My first attempt had recommended that the justices reverse a lower court ruling. But I couldn’t get over the nagging doubt that I was wrong.

In those days, law clerks were forbidden to work remotely out of concern for information security. (We didn’t love the rule then, but in the aftermath of the leaked draft of the 2022 abortion decision, perhaps it makes sense now). So I sneaked out of bed and drove back to the court. I reread the briefs and found the arguments on each side so close, and the law so uncertain, that I wrote a second memo suggesting the opposite outcome.

Law clerks from the other justices’ chambers were similarly perplexed. The justices, we knew, could reasonably reach opposing conclusions because the case was just that hard. If you’d asked me then for an honest assessment of which side should win, I would have answered with three simple words: I don’t know.

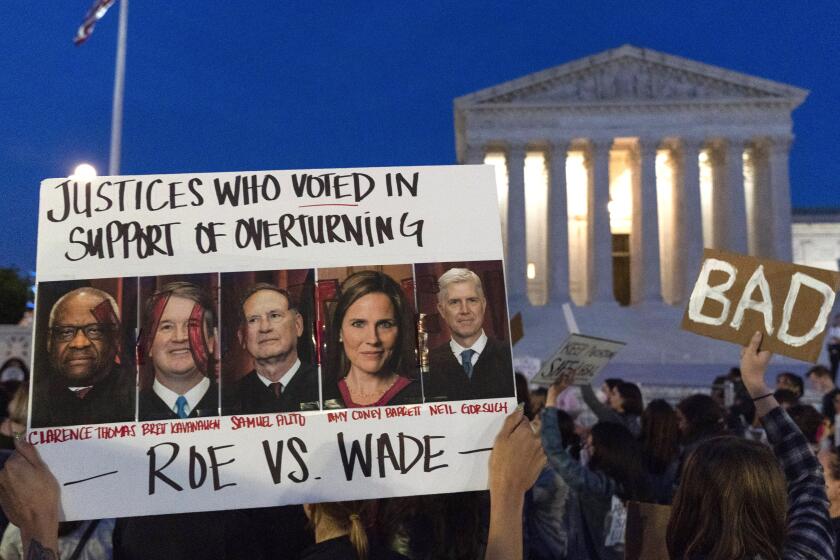

The leaked opinion’s ignorance of the true history of abortion — or worse, its duplicity — suggests that politics not the law is driving the fall of Roe vs. Wade.

Yet when the justices met to vote on the case at their private conference, by all accounts they needed little discussion to reach their conclusion. And when the court issued its opinion shortly thereafter, it was as breezy as it was self-assured. The sense of complexity that I had struggled with in my dueling bench memos was nowhere to be found. Instead, the justices asserted that there could be but a single correct answer, one they alone were capable of delivering.

That is when it dawned on me. The Supreme Court has an overconfidence problem.

Across America’s history, our greatest leaders have often possessed the virtue of humility. Consider Benjamin Franklin’s famous pursuit of self-improvement, in which he openly acknowledged his weaknesses and sought to better himself by practicing 13 virtues, one by one. (The last virtue on Franklin’s list? Humility.) Or consider George Washington, who laid down his sword after the Revolutionary War and later walked away from a third term as president, twice putting his ego aside to allow others a chance to lead.

If today’s justices were similarly humble, they would freely admit that sometimes, especially in the difficult cases that divide our society, they cannot find a clear answer. Our Constitution, after all, is a remarkably short, 236-year-old document. History and precedent are often ambiguous and conflicting. On issues ranging from abortion to free speech and gun safety to freedom of religion, there are close arguments — not to mention intense interests — on both sides. Recognizing this nuance is not a sign of weakness. It is a sign of intellectual honesty and strength.

Antiabortion forces are trying to use the antiquated Comstock Act to justify a national abortion ban. But if the Supreme Court is true to its own reasoning, that won’t fly

Today’s legal culture and our polarized politics, however, demand certitude. And the court tends to deliver. Gone are the days when justices would set aside personal views and uphold a contentious law because, in the words of a watershed 1937 ruling upholding the minimum wage, “Even if the wisdom of the policy be regarded as debatable and its effects uncertain, still the legislature is entitled to its judgment.”

Instead, today’s justices often show no doubt even in the hardest cases, and even if their rulings require undoing decades of precedent. Take Justice Neil M. Gorsuch’s blithe assertion that a difficult civil rights and free speech conflict involving a Christian graphic designer who refused to make wedding websites for gay and lesbian couples had an “obvious” answer. Or Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr.’s conclusion that Roe vs. Wade was “egregiously wrong” because the reasoning it used to uphold the right to abortion — reasoning that was embraced by nine of the 12 Republican high court appointees who voted on abortion before Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization — was “exceptionally weak.”

“Obvious.” “Egregiously wrong.” “Exceptionally weak.” This is language that only the most overconfident people use.

Of course, the Supreme Court must still decide cases: It cannot say “I don’t know” and stop there. But crafting decisions that honestly confess when a legal question is hard could be liberating. Such candor would allow the court to achieve other important aims — shoring up trust in the democratic process and congressional lawmaking, preserving legal stability by deferring to earlier rulings and doing the least harm possible.

Indeed, the court used to engage in just such a humbler approach. Even three years ago, for example, in a dispute involving then-President Trump’s effort to block a New York subpoena seeking his financial records, the court didn’t simply assert that it could uncover a singular answer in the Constitution. Instead, it recognized the important interests on both sides of the case and asked which side — Trump or New York — could more easily minimize the harm of an adverse ruling. Because Trump had better options for avoiding burdensome subpoenas than New York had for obtaining the information necessary for its criminal investigation, the ruling went against Trump.

When race can no longer be considered for college admissions, equity advocates must take aim at the root causes of educational inequality.

The justices wisely took the same approach in other divisive disputes in 2020 — over LGBTQ+ rights, immigration and a second Trump subpoena case (this time, they ruled in Trump’s favor). By pointing out productive, post-defeat responses to each of these decisions, the court made sure that the losing groups would have options for recourse other than attacking the court’s credibility.

And it worked. It is hard to imagine now, but a bipartisan 58% of Americans approved of the court in 2020. Sadly, with the new makeup of the court since Justice Ruth Ginsburg’s death in 2020, the court has abandoned humility in favor of overconfidence and its public support has fallen precipitously, with just 40% of Americans backing the justices.

In the 2023-24 term, the Supreme Court will decide major issues such as the constitutionality of gun restrictions for people subject to domestic violence restraining orders and the future of the administrative state. The justices’ willingness to acknowledge complexity in the cases will be as important as their bottom-line decisions.

The key to restoring the public’s trust in the Supreme Court is not for the justices to confidently bellow that they are always right, or to complain that the court must be treated as if it were above reproach. Just the opposite. The justices should admit that they don’t have all the answers and allow the court to resume the modest role in society that serves it — and the American people — best.

Aaron Tang is a law professor at UC Davis and a former law clerk to Justice Sonia Sotomayor. This essay was adapted from his book “Supreme Hubris: How Overconfidence is Destroying the Court — and How We Can Fix It.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.