Commentary: Goodbye gas. New all-electric homes show how to live without fossil fuels

- Share via

From the outside, the rows of tile-roof houses in a new community in Menifee don’t look much different from those in other subdivisions cropping up in this fast-growing city in Riverside County. But on the inside, these all-electric homes are revolutionary, offering a glimpse of the zero-emission future we should be hurtling toward to fight climate change and adapt to its effects.

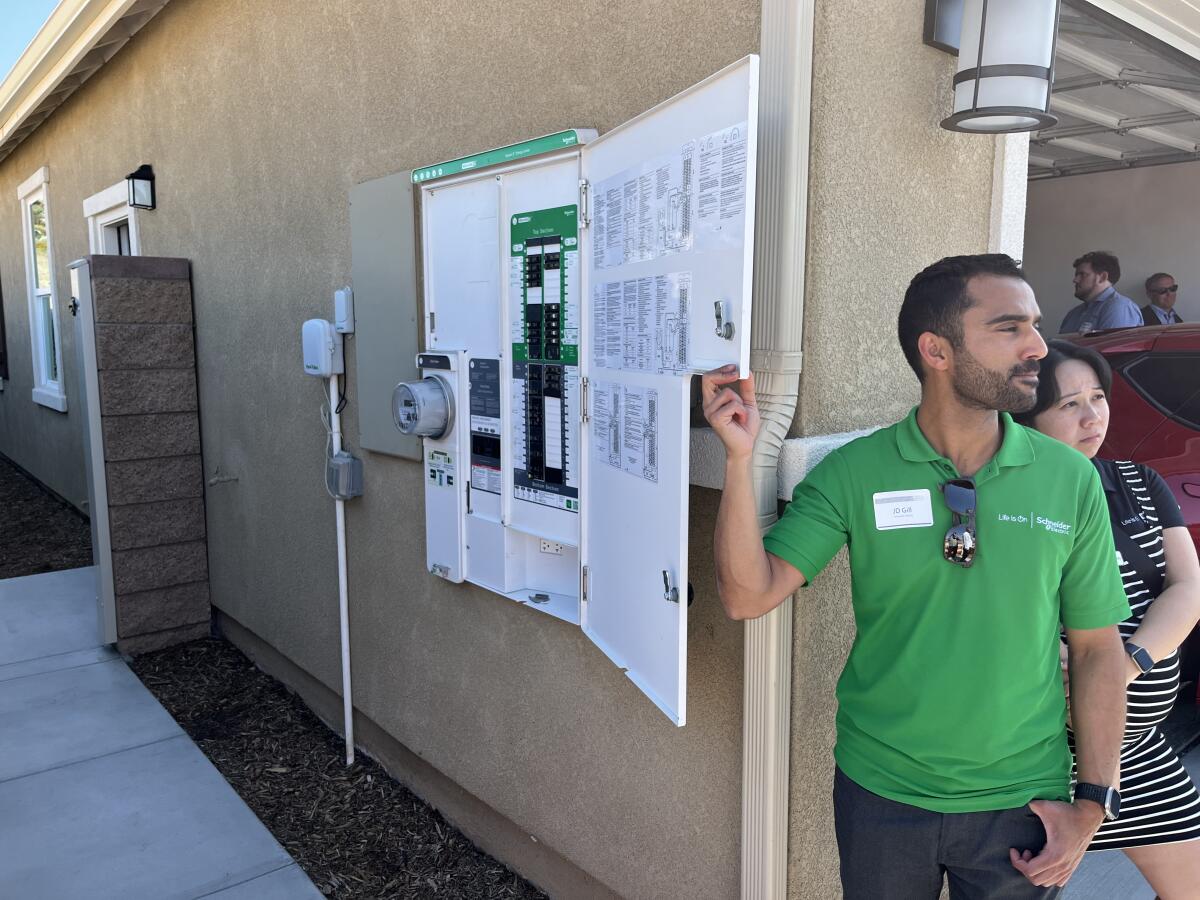

All the houses in the Durango and Oak Shade at Shadow Mountain communities, two adjacent KB Home subdivisions I visited in May for an opening event, were built without natural gas hookups or appliances. Each of the 219 homes comes with rooftop solar panels, heat pumps for heating and cooling, induction cooktops and other energy-efficient electric appliances, and a smart electrical panel that manages energy use. In the garage is a battery storage system that can power the home during an outage and in the evenings when the cost of electricity from the grid is higher.

They’ll also soon be connected to a shared community battery storage facility the size of a shipping container that’s a backbone of a system known as a microgrid. It will allow residents to disconnect from the electrical grid during an outage, and use the backup power to keep their lights on for a few days.

I expected these homes to come with a premium price tag, given their futuristic amenities. But they start around $520,000, and a 2,900-square foot, four-bedroom, two-bath Spanish-style home recently sold for about $590,000. Buyers aren’t paying extra for technology that would otherwise cost $30,000, according to the homebuilder, because the project was subsidized by a $6.65 million U.S. Department of Energy grant.

House Republicans, and some Democrats, are using their power to pass legislation that would preempt nonexistent bans on gas stoves. It’s really just a bad-faith attempt at anti-climate virtue-signaling.

The homes have other energy efficiency features such as spray foam insulation under the roof to help cool the attic and the living space below. The houses are essentially “like a Yeti cooler,” as one official with SunPower, the company that provided their solar and battery-storage systems, told me. That’s life changing in this corner of Riverside County where summer days often exceed 100 degrees and utility bills climb painfully high.

After spending a few hours checking out the homes’ energy-smart features and listening to company and government officials talk up their climate-friendliness and resilience, I was almost envious. The people moving into these houses are living in a world that, for now, remains a distant reality for most Californians for whom a fossil fuel-free home is still very much a pipe dream. And it highlighted how much work there is yet to do by state officials to ensure all Californians start to benefit from home electrification as that need becomes increasingly obvious in a world altered by climate change.

Underscoring that feeling for me was a remark by a California Energy Commission official in attendance, who noted that new construction accounts for less than 1% of the state’s housing stock in any given year.

New York just became the first state to ban gas hookups from new buildings to fight climate change and air pollution. What’s preventing California from doing the same?

California has 14 million homes and builds only about 110,000 new housing units a year. So even if all new homes are built with at least one electric heat pump, as the Energy Commission expects, that would account for only about 8% of all homes by 2030, 14% by 2040, and 20% by 2050. That’s not anywhere near fast enough to slash climate-warming emissions, which means that most of this transition will have to happen by replacing appliances in existing homes.

For now, California remains heavily dependent on fossil fuel in daily life, especially the methane gas that powers the majority of home appliances. For most of us, the transition to zero-emission electric living will be far more complicated, messy and slow than buying a new home.

The furnaces, stoves, clothes dryers and water heaters in our homes and businesses may not seem like big polluters individually, but they all add up to a lot. Buildings are one of the biggest emissions sources in California, responsible for about 25% of its climate pollution. But California still lacks the kind of straightforward zero-emission targets for buildings that it has already adopted for other major pollution sources like electricity generation and new cars.

Because home appliances like furnaces and water heaters can last 15 years or longer, scaling up action over the next few years is critical if we are to get on a path to zero out greenhouse gas emissions by midcentury and avert catastrophic levels of climate change.

A recent report by Rewiring America, an electrification-focused nonprofit organization, found that to meet those climate targets the U.S. has to dramatically increase the pace of replacing fossil-fueled appliances and cars over the next three years. That would mean purchasing about 14 million more electric heat pumps, water heaters, stoves, rooftop solar systems and electric vehicles above what’s expected.

While California has some laudable goals, including Gov. Gavin Newsom’s target of installing 6 million heat pumps by 2030, state officials acknowledge that much greater numbers will be needed to put California on track to achieving a carbon-neutral economy by 2045.

State air quality regulators plan to end the sale of new gas-fueled furnaces and water heaters by 2030, and the Inflation Reduction Act and its array of consumer rebate and incentive programs should help bring down the cost of replacing them with electric heat pump models. But state leaders need to establish clear and ambitious targets for home electrification, while pursuing creative solutions such as establishing a neighborhood decarbonization program to retrofit entire low-income communities with electric appliances and infrastructure at the same time.

As an environmental reporter, I write about how climate change is hurting people and the planet. But at home, I’ve struggled to talk about it with my own daughters.

There are reasons for optimism, including the home construction industry’s embrace of electric technology. Heat pumps are doing particularly well, now accounting for more than 50% of the market in new construction.

But I’ve also encountered troubling stories that make me really concerned about the slow and uneven pace of change. I’ve heard from homeowners struggling to turn their houses all-electric and their travails through a thicket of contractor resistance, government red tape and other obstacles. I’ve spoken to community leaders who fear that low-income tenants and other disadvantaged groups will end up shouldering most of the burdens of electrification, like higher utility bills and rent increases landlords are likely to impose to pay for electrical upgrades. I’ve covered legal setbacks and fossil fuel industry resistance operations that are hindering the transition to healthier, gas-free homes.

At my family’s 1950s-era tract house, I want to replace the gas water heater, furnace, dryer and stove with heat pump and induction models as soon as we can afford to. But I know that will be a long, expensive journey with no shortage of complications — and electrical work.

For now, our entry point is a $100 countertop induction cooktop we’ve started to use instead of our gas burners. It boils water faster and doesn’t pollute the air, but draws so much electricity that we can’t turn on other kitchen appliances at the same time or it overloads the circuit.

Whether we rent or own or have a new or historic home, everyone should be able to live in an efficient, non-polluting and climate-ready dwelling even if it wasn’t purpose-built for an all-electric world like the new construction in Menifee. None of us should have to wait decades for that to be our reality too.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.