Editorial: Court’s domestic violence gun ruling shoots first, asks questions ... never

- Share via

If a foreign enemy wanted to destroy the United States without anyone noticing, it might try to find a way to weaponize the rights we cherish and use them against us. That way, every action we take to defend our liberty would actually be a blow against it.

But who needs enemies when we have the U.S. 5th Circuit Court of Appeals?

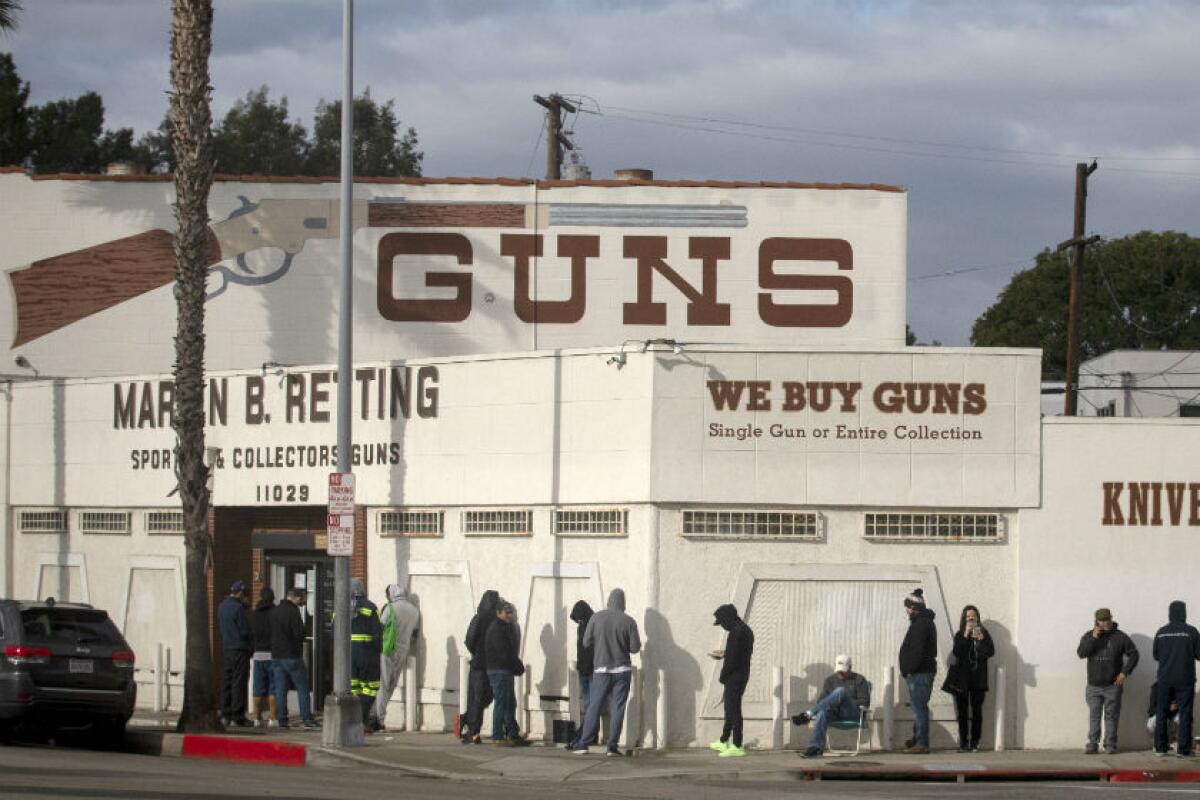

The court issued a shocking ruling last week that puts guns back in the hands of domestic abusers and could ultimately be used to undermine a host of “red flag” laws in more than a dozen states, including California, that temporarily separate potentially violent people from their guns.

How violent? A Texas man named Zackey Rahimi assaulted his girlfriend and then agreed to a restraining order that prohibited him from possessing firearms. Nevertheless, he later shot several times into the home of a person to whom he sold drugs; got in a car accident in which he shot at the other driver, fled the scene but returned to shoot again; shot into a law enforcement vehicle; and shot several times into the air after a Whataburger restaurant declined his friend’s credit card.

Perhaps it’s the fate of the United States to watch its soul die along with the 19 students and two adults shot to death Tuesday at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas.

Rahimi obviously was armed and dangerous despite the restraining order. Police searched his home and found two guns, and he was indicted for violating the order.

The 5th Circuit Court ruled that the federal statute prohibiting individuals from possessing a firearm while under a domestic violence restraining order is unconstitutional, and therefore Rahimi never should have had to give up his guns. Interpreting last year’s U.S. Supreme Court ruling in New York Rifle & Pistol Assn. vs. Bruen, the appeals court ruled that the Constitution prevents interference with his right to his guns. Why? Because domestic violence restraining orders didn’t exist in 1789 when the 2nd Amendment was written. Bruen requires that gun restrictions have some historical precedent to amplify what the drafters must have been thinking.

Yes, the court in Rahimi’s case acknowledged, there were laws back then that prevented some dangerous people from having guns, but those precedents don’t count in this case. They applied to entire classes of people, like suspected potential rebels, not to people against whom courts had made individualized findings of dangerousness. Besides, the court said, if guns can be taken out of the hands of particular people based on their acts, what’s to prevent government from also taking away guns for not recycling or not driving an electric car?

Tentative support by some Republican members of Congress for red flag laws is a woefully inadequate response to mass killings, and misses the main point: Ready access to guns is driving the violence.

Seriously, now — temporarily removing an instrument of violence from a demonstrably violent person might lead to disarming someone for tossing a glass bottle in the trash? Requiring that a violent person hand over his or her gun is more constitutionally suspect than disarming an entire class of people?

There were no semiautomatic weapons or Saturday night specials in the 18th century, yet the courts insist that historical context can impose no restriction on those weapons — while it does restrict our ability to enact laws to defend the public against people who would wield those weapons against us.

The gun industry and conservative-dominated courts have selectively ignored the 2nd Amendment’s language about a “well-regulated militia” and “the security of a free state” and have turned that constitutional protection into a national suicide pact. Somewhere, foreign enemies who would do us harm must be reading the Rahimi opinion, unloading their own weapons and thinking, “Why bother?”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.