Op-Ed: South L.A. deserves better healthcare access. Fair Medi-Cal payments can help

- Share via

COVID-19 kills some more than others. During the pandemic, coronavirus infected and killed people of color at disproportionately high rates. But getting COVID under better control has not addressed the underlying health disparities that plague low-income communities of color. In community listening sessions, my colleagues have heard statements like: Is the government going to give us a jab in the arm and then walk away, leaving us with all these untreated illnesses?

“All these untreated illnesses” are the epidemic of untreated diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and cancer that devastates majority Black and brown communities including South L.A. The question reflects structural problems we have not solved. Reducing health inequities requires fixing the structures that perpetuate them. High on that list is Medicaid, our country’s separate and unequal insurance system for low-income Americans.

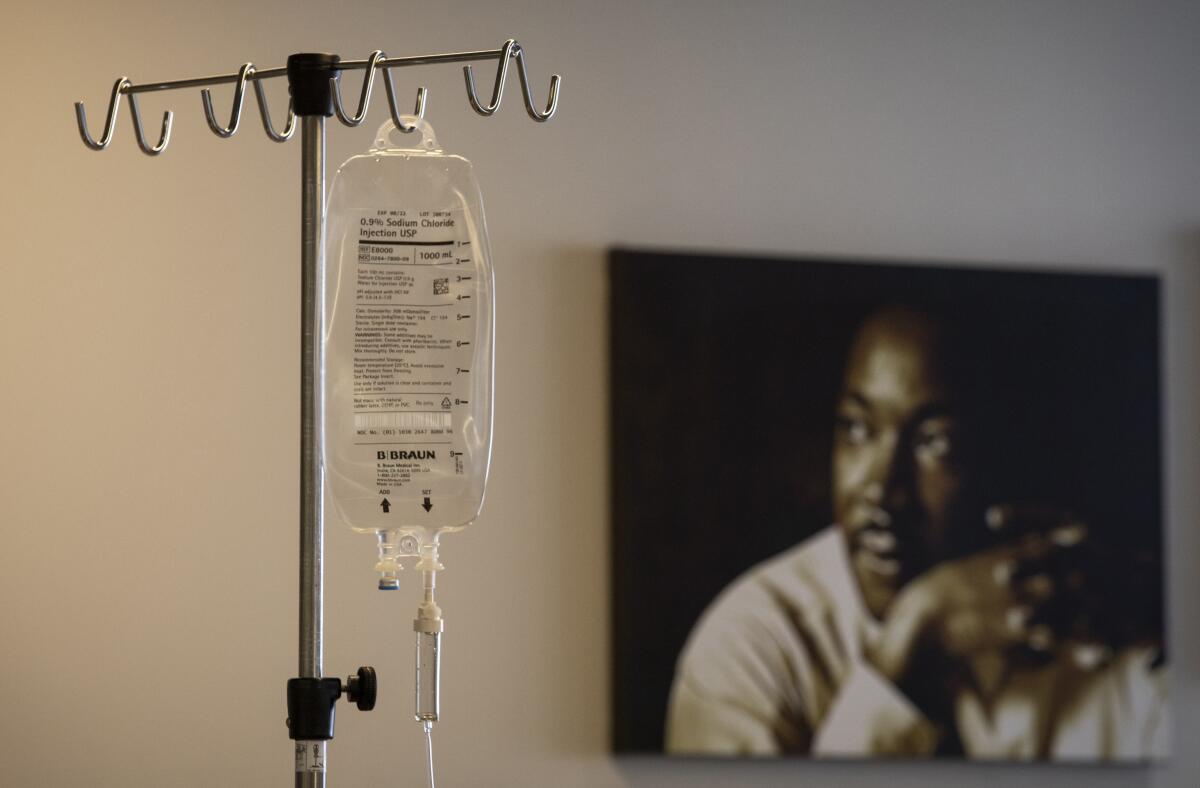

Officials say the Omicron variant has flooded the emergency room at Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital, ground zero for hospitals besieged by a winter surge, with people who are not as sick.

Occasional difficulties that people experience when getting care through private insurance — waits, denials of care, unavailable or inaccessible providers — are chronic and egregious for people who rely on Medicaid. In California, a major contributor to this problem is low provider payments. Medi-Cal, the state’s Medicaid system, pays less than Medicare does for the same services and a fraction of what private insurance pays, as data from recent years show.

The result: Too few doctors can afford to practice in communities that rely on Medi-Cal, meaning these communities — predominantly people of color, who make up more than two-thirds of Medi-Cal patients — struggle to access healthcare. This dynamic contributes to “healthcare deserts,” places with severe shortages of doctors and basic healthcare services.

I’ve seen firsthand how urgent it is for California to dismantle our separate and unequal health system and bring Medi-Cal payments into parity with its public insurance partner, Medicare.

South Los Angeles, where I run a healthcare system, is a healthcare desert. Our community has high rates of poverty and is majority people of color. We have 1,400 fewer primary and specialty care physicians than our population needs. Data show that more affluent communities in California have 10 times as many doctors as we do. It’s no coincidence that our diabetes rates are three times higher and life expectancy 10 years shorter than California averages. There are so few providers that when residents need care, it simply isn’t available.

As a result, patients get sicker than they should, often ending up in our emergency department to receive care when their treatable conditions have advanced to severe, even life-threatening stages.

This year, for example, we’ve provided emergency department services for a patient who has needed gallbladder surgery since March. He could not get it scheduled through his Medi-Cal coverage until December. He comes to our emergency room when the pain becomes unbearable. Our emergency medicine doctors help him manage his pain, but they are not the right doctors to treat the underlying condition. They expect that he will eventually be hospitalized with a life-threatening complication.

In South L.A., accessing an obstetrician or midwife is so difficult that women regularly come to our emergency department for pregnancy-related services and follow-up, not just deliveries. The lack of access to reproductive services is especially troubling given that nationally, mortality rates are up to four times higher for Black mothers than for other women.

Low Medi-Cal payments don’t just discourage doctors from practicing in low-income communities. They can also incentivize health system intermediaries to restrict the availability of services.

When public med schools drop affirmative action, they admit fewer students from underrepresented racial groups.

When payments don’t cover the costs of care, middle managers in the healthcare system, including health plans and independent physician associations, can inappropriately restrict access to that care. There are several ways this works. One way is to exclude providers from their networks. Middle managers sometimes decline to contract with doctors to avoid paying for their services. Another way to restrict access is by allowing patients to see doctors for consultations, but then refusing to authorize the same doctors to provide curative treatments and procedures.

A talented surgeon practicing in our medical group experienced these problems earlier this year. Although patients were referred to him by their health plans and independent physician associations for requested consultations, those middle managers then refused to authorize him to perform the needed procedures. He cared passionately about our community, but he was defeated by the inability to perform crucial surgeries for his patients. He left.

California should increase Medi-Cal payments for doctors working in underserved places like South L.A. The state already provides supplemental funding for hospital care at “disproportionate-share hospitals’’ — institutions that serve communities with concentrated poverty. We should apply the same concept to Medi-Cal payments for outpatient care delivered in these communities.

Compensating doctors at parity with Medicare would improve the financial viability of medical practices in low-income communities and make it possible to recruit and retain physicians to provide the services patients need.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has already expanded Medi-Cal access and spearheaded the state’s new CalAIM program broadening Medi-Cal coverage to services that address social determinants of health, such as access to food and temporary housing. These are good steps toward equity.

It is time to build on this work to achieve the ultimate goal: access to quality healthcare for all Californians. Fair Medi-Cal payments for safety net communities like ours would allow doctors to do the work we are called to do: heal.

Elaine Batchlor is a physician and the CEO of MLK Community Healthcare and Martin Luther King Jr. Community Hospital in South Los Angeles.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.