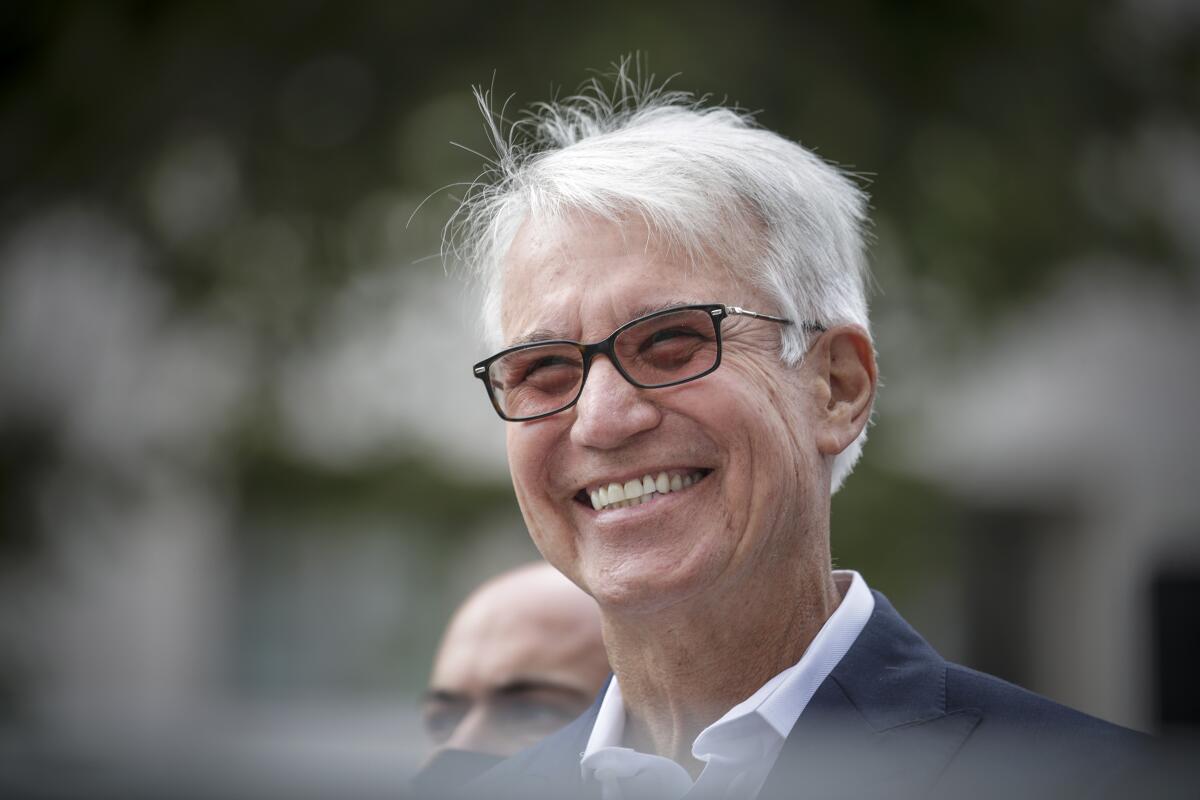

Editorial: Now that a second recall effort has failed, let George Gascón do the work he was elected to do

- Share via

Now that a second attempt to recall Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón has failed in the petition phase, let’s hope there is not a third.

Voters heard Gascón’s change-oriented proposals for the office during a long 2020 campaign and said “yes,” electing him over a two-term incumbent and putting him in office for a full four-year term that is not even half over. Voters can review his record in 2024 and decide then whether to keep him, assuming he runs again, or to move in a different direction.

Opponents certainly had every opportunity to cut his tenure short. An effort last year to gather the needed 566,857 valid voter signatures to put a recall on the ballot barely got off the ground for lack of money, but the second attempt was well funded and culminated in petitions being sent to virtually every registered voter in Los Angeles County.

Despite a nationwide media campaign that tapped into an anti-reform movement spearheaded by political conservatives and broadly backed by law enforcement groups, even that effort fell short.

That’s a good sign. Important criminal justice reforms have moved forward in California since the Arnold Schwarzenegger administration, and the electorate has consistently defeated a concerted rollback effort — until June 7, when San Francisco voters recalled Dist. Atty. Chesa Boudin. Reform won important victories elsewhere in California and around the nation on the same day, but a Gascón recall later this year, in the nation’s largest local jurisdiction, might easily have stalled the movement.

The recall movement against Dist. Atty. George Gascón is a misguided attempt to assign blame for the last two years of political turmoil, disruption, anxiety and violence.

Criminal justice reforms in California focus on carving back some of the sentencing excesses that characterized the 1980s and 1990s, when the state engaged in a massive program of prison construction, bolstered by legislation and ballot measures that amped up punishment and targeted drug crimes alongside murder and violent assault.

Reform began in earnest with a lawsuit challenging overcrowding in California’s bloated prison complex. The state faced either a huge inmate release ordered by federal courts or a more thoughtful and pragmatic downsizing that differentiated between violent and less serious crimes. Reforms sought to alter counties’ financial incentives to send convicted offenders to state prison or keep them at home and participating in rehabilitation and other anti-recidivism programs. Criminal justice reform also put a premium on data gathering and analysis.

Gascón quickly became a reform innovator. For example, as San Francisco’s district attorney, he co-wrote Proposition 47, a 2014 measure to end felony prosecution for drug possession and for smaller property crimes.

More recently, reforms have focused on racial equity and curbing police misconduct, especially following the 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis. Gascón has been a leader on those issues as well.

These were and remain the correct moves for Los Angeles County, where voters have consistently backed corrections to a criminal justice system that locks people up too often and for too long, and is inadequately effective at directing former offenders to responsible, crime-free post-prison lives.

But his leadership also earned him the enmity of anti-reform forces who labeled him a tool of George Soros, a financier and philanthropist who donates heavily to progressive prosecution candidates, including Gascón.

A lawsuit by line prosecutors against their boss, Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, is an assault on voters.

His critics have blamed him for nearly every high-profile crime since he took office, even though the jump in L.A. crime rates that began when strict pandemic lockdowns ended and Floyd was killed has been mirrored in jurisdictions around the U.S. They blamed him for “zero bail,” even though his policies duplicated or were outflanked by the state Judicial Council, continued by the L.A. County Superior Court and to a large extent cemented into law by a state Supreme Court ruling that held unaffordable bail unconstitutional.

Gascón was blamed for an increase in shoplifting — even though a majority of reported shoplifting crimes are misdemeanors outside his purview. He was blamed for violent “smash and grab” robberies, which he has prosecuted, and for theft of goods from Union Pacific trains as the rail company cut back its own security.

In recent months, perhaps because of the recall effort, Gascón has begun to do a better job of explaining and defending basic reform policies. We need more of that — not merely because yet another recall drive would be a waste of resources, but because voters sought in Gascón a leader who does not merely prosecute, but engages in a dialogue with residents about police, prosecution and prisons, and advocates for constructive and safety-enhancing change.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.