Op-Ed: The West has no business pushing Ukraine to compromise with Putin

- Share via

KYIV, UKRAINE — Valera Kondratenko, 32, would feel right at home working on Wall Street and living on the Upper East Side of Manhattan. He has an advanced degree in finance, works as the investment director for a private equity fund, speaks perfect English and tweets about Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

In fact, Kondratenko lives in Kyiv.

He’s doing everything he can as a civilian to support Ukraine’s war effort — he helped found a grassroots group that imports vehicles for the armed forces — and he’s hopeful about the outcome of the fighting. But he’s also unsentimental.

“If there’s any hint of compromise with the Russians,” he says flatly, “there’s no future for me in Ukraine. If we give them Donbas, it’s only a matter of time before they take another bite of the apple. I can’t build a future for myself or my family under the shadow of a Russian takeover.”

Biden arrives in Europe for G-7 and NATO summits as the world’s leading democracies grapple with war in Ukraine as well as their own domestic issues.

As Russia’s war of aggression enters its fifth brutal month, the Group of 7 leaders have committed to stand with Ukraine “as long as it takes.” But that phrase means many different things to different people, and even some of Ukraine’s most stalwart European and U.S. supporters, making grim World War I analogies and citing dwindling voter approval of the conflict, are starting to suggest terms for a compromise settlement. One proposed scenario: Western reconstruction aid and security guarantees for a divided country modeled on North and South Korea.

After a month in Kyiv and conversations with dozens of Ukrainians, I see no support for this position inside the country.

White-collar professionals, blue-collar workers, public officials, civilians and soldiers, for most Ukrainians, it’s a given: A compromise settlement would be no more than a pause, allowing Russia to regroup for another push — yet a third invasion, in the next few years, to seize the rest of Ukraine.

No one I’ve met in Kyiv believes Western security guarantees would contain the occupiers after a compromise settlement, as they do in Korea. Many focus on how the uncertainty created by dividing the country would cast a pall on the foreign investment essential for postwar reconstruction. Still others predict there would be a popular uprising — remember the 2004 Orange Revolution and Maidan protests of 2013-14 — if President Volodymyr Zelensky were even to entertain negotiations about ceding territory to the Russians.

And to a person, everyone I’ve spoken with assures me that Ukrainian forces will fight on, with or without Western help, until the Russians are expelled, pushed back beyond the borders established when Ukraine was created in 1991.

Will inflation and energy woes crack Western unity over Ukraine? Putin likely hopes so.

A Ukrainian poll released this week by the Wall Street Journal confirms what I’ve heard in Kyiv. A full 89% of the Ukrainians surveyed opposed trading conquered land for peace, and 81% opposed allowing Russia to keep the territory it annexed in 2014.

What’s surprising isn’t this Ukrainian consensus. It’s the way so many in the West, even those who supported Ukraine at the start of war, are now going wobbly.

Don’t those endorsing a settlement remember what Vladimir Putin wrote last year in his infamous essay about Ukraine and Russia? He insisted that the Soviet Union had invented Ukraine, carving it out of what was historically Russian territory, and promised to begin “gathering” — read annexing — lost “Russian lands.”

True, a lot of what Putin says is bluster. But Mariupol, Bucha, Severodonetsk, the 2014 annexation and current attempts to Russify recently captured cities in southern Ukraine should leave little doubt. The Russian strongman means what he says about retaking Ukrainian territory and wiping the Ukrainian nation off the map.

The Times’ Marcus Yam is back in eastern Ukraine, where fighting remains fierce and residents continue to endure with no end in sight.

Can Ukraine win the war with Russia? No one knows. Two historical parallels, Afghanistan and Vietnam, suggest that it could. Determination and inventiveness count for a lot in war, and small, less developed, less well-equipped nations can beat back big powers if they want what they’re fighting for badly enough.

I saw a little of this myself in recent weeks as I pieced together what happened in Irpin, the city just north of Kyiv that stopped the Russians from entering the capital. In the first days after the invasion, local militia had no more than a handful of automatic rifles and shoulder rocket launchers. But unlike the invaders, they knew the terrain and had abundant intelligence from civilians who reported the Russian positions, allowing just a few score of ill-equipped men to destroy long columns of Russian tanks and other military vehicles.

It doesn’t always work this way — scrappy defenders don’t always win. The Russian war in Syria is a less encouraging parallel. A big army willing to level cities and massacre civilians can sometimes prevail over time.

But it’s far too soon for the West to predict the outcome in Ukraine, and it will never be appropriate for us to dictate the terms of a settlement. We’re not fighting or dying. The Ukrainians are — and it must be up to them to decide when and how to settle with Russia.

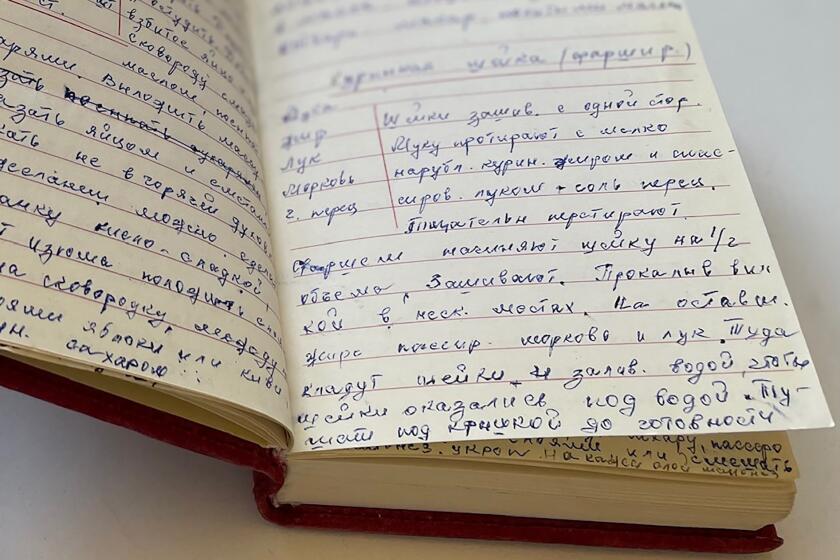

A grandmother’s handwritten instructions for borscht, dumplings and stuffed chicken necks are recipes for resilience.

What’s hard to understand: why this isn’t obvious in the West. Kyiv needs more heavy weaponry from the U.S. and Europe, the sooner, the better. But loose talk and weak-kneed signals may be as damaging as delayed aid.

People on both sides of the conflict listen carefully for cues about public opinion in the U.S. and Europe. And reckless musing about a settlement could undermine the odds on the front lines, disheartening Ukrainians even as it encourages Putin.

Tamar Jacoby, president of the U.S. policy nonprofit Opportunity America, has been volunteering in Poland and Ukraine since early March, helping to provide relief for refugees and reporting on the war.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.