Op-Ed: Removing Indigenous concepts from ethnic studies sends a terrible message to California’s students

- Share via

Removing the Indigenous concepts In Lak’ech and Ashe from California’s Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum, on the false premise that they are religious, sends a message to all of the state’s students, especially those who are Chicanx, Black and Native, that their cultures are not worth fighting for.

Last September, the Californians for Equal Rights Foundation and three San Diego parents sued the California Department of Education and the California State Board of Education, claiming that In Lak’ech was an Aztec prayer and Ashe was a religious chant. The suit argued that including texts that involved these concepts in the state’s recommended ethnic studies curriculum violated the Establishment Clause of California’s constitution. Last week, even though they denied the allegations and did not admit to any liability, the defendants settled the case to avoid further litigation. They agreed to excise both affirmations from the model curriculum and communicate those deletions to districts, schools and education boards.

The Californians for Equal Rights Foundation, a group that has worked against ethnic studies and anti-racist initiatives in San Diego schools, claimed that one of the In Lak’ech texts referenced in the recommended ethnic studies curriculum was an “Aztec prayer.” That poem, written by Luis Valdez and often used in California ethnic studies classes as an affirmation promoting values such as respect and empathy, is based in Mayan philosophy, not religion. The lawsuit also argued that an Ashe affirmation in the model curriculum was a religious chant, even though Ashe is a concept that refers to the power to effect change that comes from the Yoruba in Nigeria.

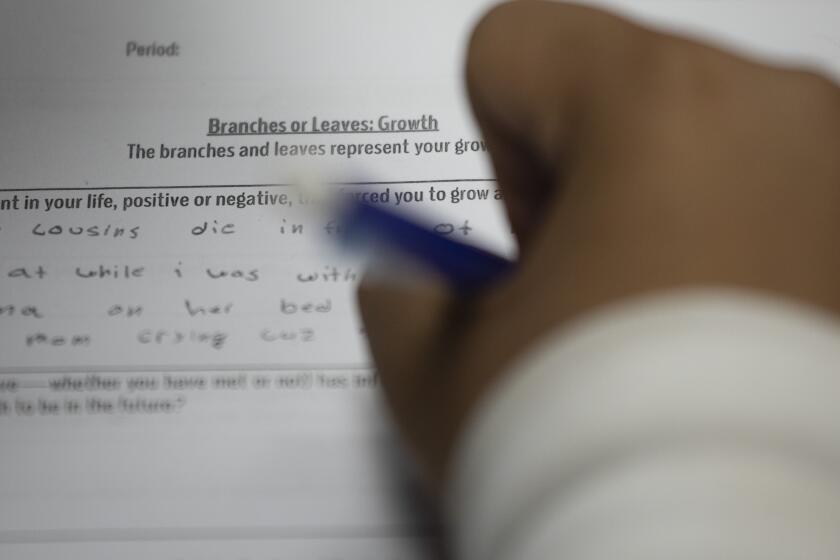

A group that has opposed ethnic studies requirements sued over the In Lak’Ech affirmation, which it claimed constituted a religious prayer.

There is legal precedent that argues for including In Lak’ech: In Arce vs. Douglas, an Arizona case, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that suppressing Indigenous knowledge constituted “racial animus” against Chicanx/Latinx.

Prior to last week’s settlement, less than 9% of the Ethnic Studies Model Curriculum was dedicated specifically to Chicanx/Latinx studies even though 55% of California’s K-12 students are Chicanx/Latinx. Eliminating the In Lak’ech Maya poem and Ashe African affirmation from the curriculum demonstrates both the lack of knowledge that leaders have about those cultures and a disinterest in standing up and fighting for students’ educational well-being, especially Black and brown students. This erasure of Indigenous knowledge is not new — American education is steeped in historical bias and racial trauma.

Many ethnic studies teachers feature In Lak’ech and Ashe in their classrooms to establish a sense of belonging, especially for Chicanx/Latinx and Black students. The removal of the concepts delivers the message to Chicanx/Latinx and African American/Black students that their communities’ knowledge and cultures are illegitimate and unworthy of defending. Notably, Chicanx/Latinx, Black and Native youth constitute the majority of California’s K-12 students but remain subject to a Eurocentric curriculum.

Our state doesn’t need another education mandate with great promise but limited impact.

Passing AB 101, which requires California students to take an ethnic studies course prior to high school graduation, was a promise to honor the historical and cultural experiences of Chicanx, Latinx, Black, Asian and Pacific Islander, American Indian and other communities of color. As long as the In Lak’ech and Ashe concepts being taught do not reflect or promote discrimination against any person or group, or teach or promote religious doctrine, they are within the parameters of the legislation.

The majority of California’s student population should not have their cultures subject to erasure every time litigation is threatened. In the end, if our educational leaders remove key principles and concepts from the model curriculum instead of fighting for their inclusion, no matter how long or costly the court battle may be, they are essentially denying California’s students an authentic ethnic studies education and, in this case, dishonoring Indigenous legacies.

Sean Arce is an ethnic studies high school teacher in Los Angeles, the co-founder of Tucson’s Mexican American/Raza Studies Department and a plaintiff in the 9th Circuit case Arce vs. Douglas. Theresa Montaño is a professor of Chicana/o studies and a practitioner and activist in ethnic studies. Guadalupe Cardona is a secondary educator in the LAUSD.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.