Column: Think you’re snorting a line of cocaine at that party? Think again

- Share via

Earlier this month, in a house on a Venice canal, three people who reportedly thought they were using cocaine died after apparently ingesting the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl. A fourth person was hospitalized and survived.

Stories about accidental overdose deaths involving fentanyl are becoming increasingly common.

There is no way of knowing, of course, but it is possible they might have lived if they’d had access to an easily obtainable nasal spray called Narcan, which reverses an opioid overdose.

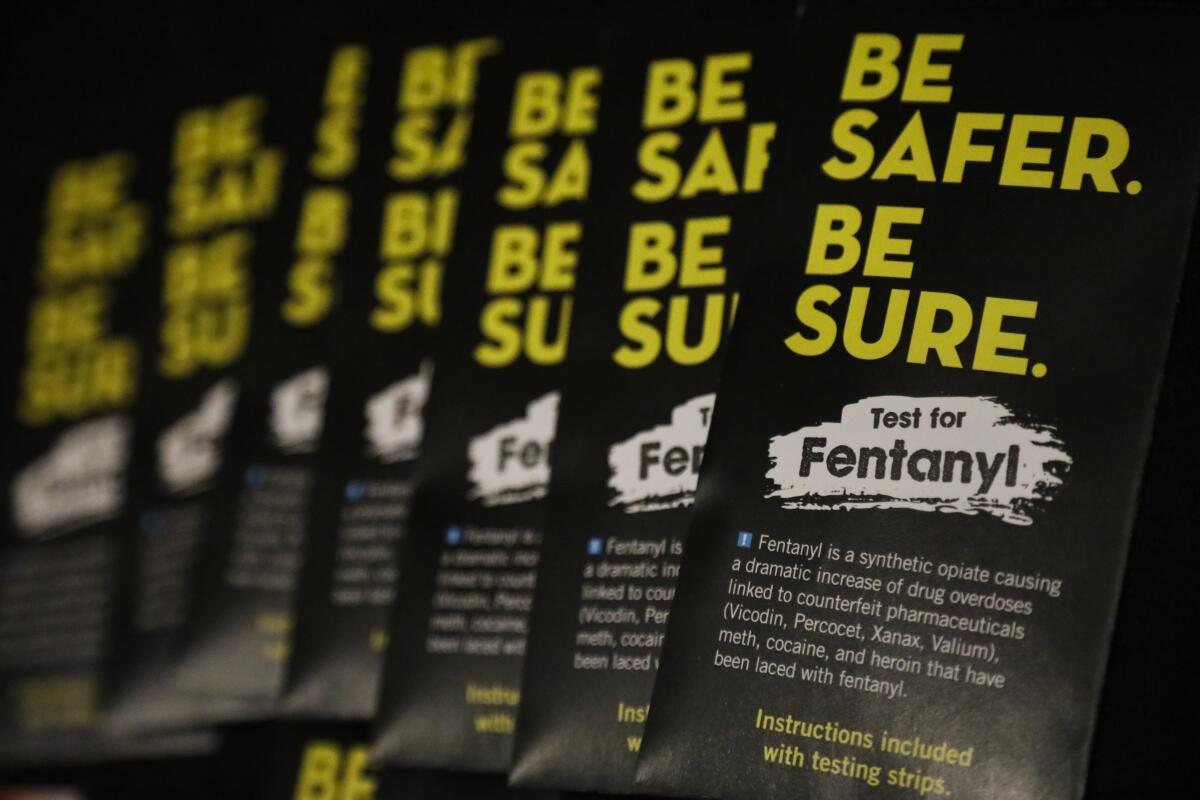

Or they might have refrained from using it altogether had they first tested the substance with an easy-to-use kit that can detect fentanyl, which kills thousands of Americans a year — and many of them don’t even know they are putting themselves in danger.

“I doubt it occurred to cocaine users to test it,” said Dr. Gilmore Chung, director of addiction services for the Venice Family Clinic. “But we see fentanyl in all drugs.”

Fentanyl, which is cheap to produce and far more powerful than heroin, can be made to look like black tar or China white heroin, cocaine or crystal meth. It can be pressed into pills and appear to be OxyContin, Xanax or Valium. The musician Prince died of a fentanyl overdose; he believed he was taking Vicodin.

“If someone tells me they are on heroin,” Chung told me, “I assume until proven otherwise that they are on fentanyl. After years of using, people become confident— ‘Hey, I know what black tar heroin looks like’ — and you test it and it’s not.”

Chung is among many specialists who take an enlightened approach to treating addiction. He practices harm reduction, a public health strategy that aims to reduce the negative consequences associated with drug and alcohol use. It acknowledges that drug and alcohol abuse is here to stay and that users are human beings who deserve respect.

This means they should have access to clean needles, for instance, which reduce the rates of HIV transmission. Or to maintenance programs that use Suboxone or methadone to prevent withdrawal and cravings, and help reduce the risk of death from overdose. (Unfortunately, nothing similar exists for meth and cocaine users.) Opioid users are urged never to use alone and to always have access to Narcan. Some countries have even introduced supervised injecting sites.

Instead of demanding abstinence, Chung helps his patients figure out how to be safer and healthier, and of course, find a path to sobriety if that’s what they are seeking.

“We meet people where they are,” he said, “as opposed to where we might like them to be.”

Thursday evening, I had a long conversation with one of his patients, Zachary, 31, who asked to be identified only by his first name, to protect his career.

Zachary’s addiction trajectory is pretty typical. In his late teens, he began using prescription opioids like Vicodin and anti-anxiety drugs like Xanax.

As public health experts became alarmed at the increasing number of opioid overdose deaths, and the enormity of the crisis was becoming clear, prescription opioids became harder to find.

“All of a sudden, everyone had switched from prescription stuff to heroin,” Zachary said. “It was so much cheaper.”

But as drug cartels realized it was easier and cheaper to produce fentanyl, heroin became scarce.

Zachary told me he has lost count of how many times he has overdosed and been revived with Narcan; he has used it to revive friends many times.

California is one of a handful of states that allows anyone to buy Narcan without a prescription and shields anyone who administers it from liability. It’s available at most CVS pharmacies.

Zachary always had it on hand.

In his mid-20s, he had already spent four years on probation ordered by drug court, though he’d never really stopped shooting heroin and cocaine. One day, he and his girlfriend scored what they thought was heroin.

He dozed off, and when he woke up, his girlfriend, who was seven months pregnant, was sitting on the floor cross-legged, her arms propped on the coffee table. When he asked if she wanted some ice cream and she didn’t respond, he touched her shoulder. “She just dropped,” he said. He revived her briefly with Narcan and called 911. She died at the hospital. The baby could not be saved.

“Turned out, it was straight fentanyl,” Zachary said. “After that, I spiraled, really out of control.”

About four years ago, he found the Venice Family Clinic and Dr. Chung after suffering seizures related to drug withdrawals.

“I was dreading going,” said Zachary, who had seen many doctors over the years to obtain Suboxone. “He was so understanding. It was the first time I’d experienced that.”

Zachary is lucky to have ended up in the care of a physician who did not judge him, shame him or force him to be abstinent to continue treatment.

“As soon as you kick someone out, it’s them against the world,” Chung said. “If you are working with them, you have a chance to get them to a better day.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.