Do we just let Sirhan Sirhan go?

- Share via

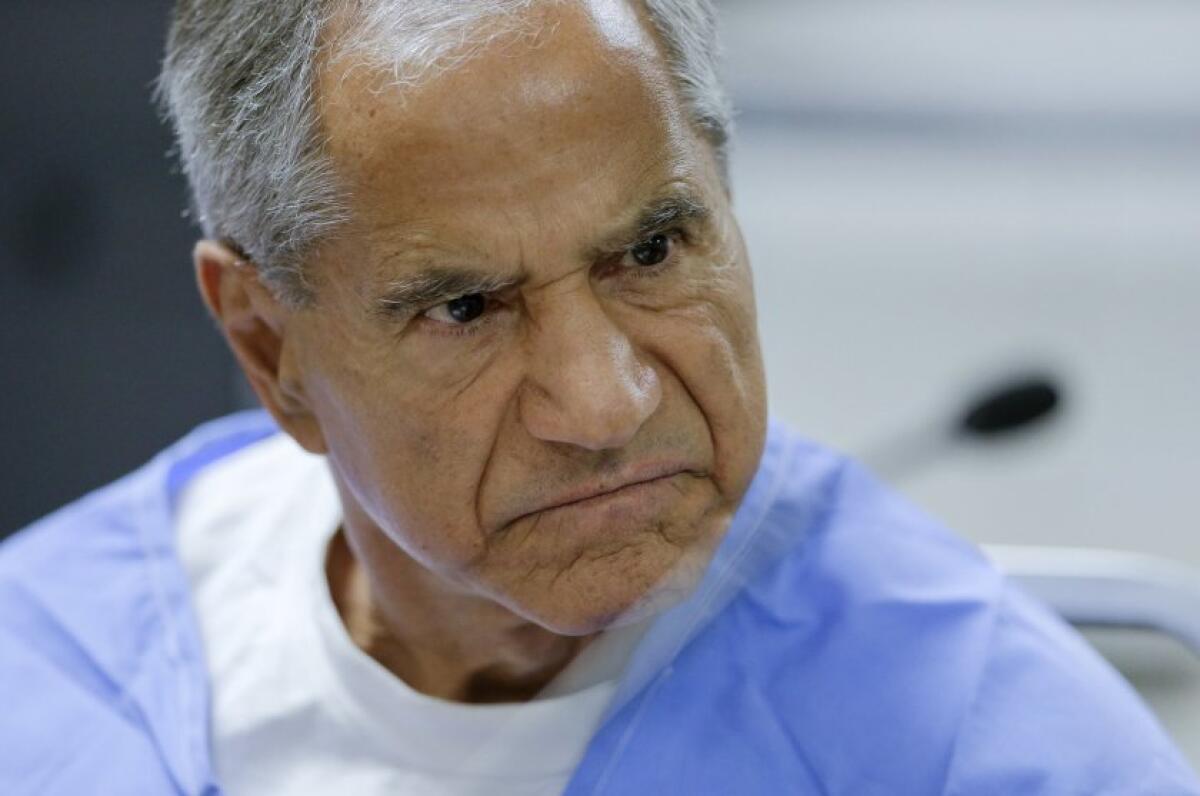

Sirhan Sirhan comes before a state parole board on Friday for the 16th time, raising the obvious question for the rest of us — should the convicted assassin of Robert F. Kennedy be released? And if not, why even bother with parole hearings?

Few people would be asking these questions except for quirks of timing and California law that put Sirhan, the Manson family killers and about 100 other condemned prisoners from that era in a very peculiar position. If they’d been sentenced for their crimes just a few years earlier or a few years later they might well have been put to death, or else sentenced to life without the possibility of parole.

But California didn’t have a sentence of life without parole in the late 1960s and early 1970s, so when the state Supreme Court temporarily invalidated the death penalty in 1972, people on death row at the time were automatically resentenced to life in prison — with a chance at parole. That’s why this distinct group of notorious killers — whose names I first saw in Los Angeles Times headlines more than a half-century ago when I was a child — repeatedly return to the news as their hearings come up.

Now I’m a member of the Times editorial board and I opine on, among other topics, our criminal justice system, where it is broken and how it should be repaired. My colleagues have joined me in pushing for shorter, more rational sentences that keep the public safe without adding needless years to a convicted criminal’s sentence. I often struggle over these positions because the issues are rarely as clear-cut as reform advocates make them out to be.

It’s been more than a decade since we weighed in on compassionate release for Susan Atkins, one of the Manson family killers whose crime put her in that odd window of time, leaving her sentenced to death but seeking release. In 2008 she was dying of cancer, and she wanted to spend her final days outside of prison.

One of my editors brought the question to me, believing, I’m sure, because of my positions in favor of reform and against sentencing excess, that I’d want us to editorialize in favor of her release. I think he, and probably most of my colleagues, were taken aback by my hard line against it.

In the most egregious instances — for example, the “special circumstances” that we currently require before seeking a death sentence — murder should result in the most severe penalty we’ve got, short of execution or torture. Atkins participated in the killing of actress Sharon Tate and numerous other people, and it seemed to me at the time that the state’s compassion was expressed in not executing her.

I chuckle now, sadly, as I reread the editorial. It seems pretty clear to me that it was written and edited by various hands with differing viewpoints.

“To allow Susan Atkins to die at home would be an act of mercy,” it says, “but not of justice.” It adds that Atkins’ case “frames two competing imperatives of the penal system — the right of society to demand justice and the desire of humans to grant mercy.”

Several years ago I wrote that the time was not right to release another Manson family member, Leslie Van Houten. It apparently was an easy call for those who wrote in and said, “No, never,” and also for those who said, “For heaven’s sake, she’s done her time.” But it wasn’t an easy call for me.

I was 9 and 10 years old and living in Woodland Hills when L.A. was rocked by the Robert Kennedy assassination and the Tate-LaBianca killings.

The frenzy around the RFK campaign made this fourth-grader take an interest in politics. Our family went to bed early, and I remember waking up the morning after the California primary when my mother walked in from the driveway where The Times had landed and said to my father, “Kennedy was shot?!” And thinking, “Of course, Kennedy was shot, Mom. That was five years ago. That’s why Johnson is president now.”

And trying desperately to push from my mind the growing realization that she was talking about a different Kennedy. My Kennedy.

Over the next several years I saw photos of the young Manson women at trial wearing outfits and hairstyles that made them look like they could have been my older sister’s friends.

Am I, in an odd sense, a survivor of these crimes, and my viewpoints about criminal punishment based in trauma and unduly colored by emotion? Has my entire generation meted out disproportionate sentences to these high-profile killers because of their particular place in the public psyche, rather than the seriousness of their crimes?

I don’t buy it. In killing a leading candidate for president, Sirhan didn’t merely kill a man, he made a direct attack on the mechanics of our democracy. It’s as if he combined murder with an attempt to overthrow the government.

If Lee Harvey Oswald had lived, would we have been OK with parole at some point? It’s hard to imagine. John Hinckley Jr., who shot President Reagan, is free, writing songs and singing them on YouTube. But his deranged attack was meant to impress an actress, not to make a political statement or affect a nation’s policy as, apparently, Oswald’s and Sirhan’s were.

As for Atkins, I do regret my position of a decade and a half ago. No, she did not show compassion when she should have. But we, as a society, are supposed to be better than our most damaging and dangerous members, and present a higher level of moral behavior.

And for Van Houten, she’s done her time. I can’t tell you why I believe that now but didn’t four years ago. Perhaps because she’s now over 70.

And yet — Sirhan. Parole? I don’t know. At the time he said why he did it, but now he claims not to remember anything about it. I would like to hear some contrition, but maybe that’s asking too much. He’s 77. Time to end this chapter in American history by granting parole? Maybe. But I’m in no rush.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.