Editorial: The judge is wrong: California’s assault-weapons ban must stand

- Share via

You can almost see these words in a gunmaker’s advertising brochure: “Like the Swiss Army Knife, the popular AR-15 rifle is a perfect combination of home defense weapon and homeland defense equipment. Good for both home and battle....” But actually, they’re the opening phrases of a federal court ruling late Friday that threw out California’s 30-year-old law ban on assault-style weapons.

There’s a lot to object to in the decision by District Court Judge Roger T. Benitez, beginning with his cynical attempt to redefine deadly firearms patterned after combat arms as just some old thing folks keep around the house to kill the odd intruder and maybe toddle off to the shooting range to use for a little fun.

In fact, assault-style weapons — which have been highly controversial since at least the 1980s — are designed for a singular purpose: to kill a large number of people in a short period of time. The fact that some hobbyists enjoy using them to pop off a few recreational rounds does not outweigh what the weapons are capable of, and why they do not belong in the hands of civilians.

The pandemic opened possibilities. Let’s embrace them.

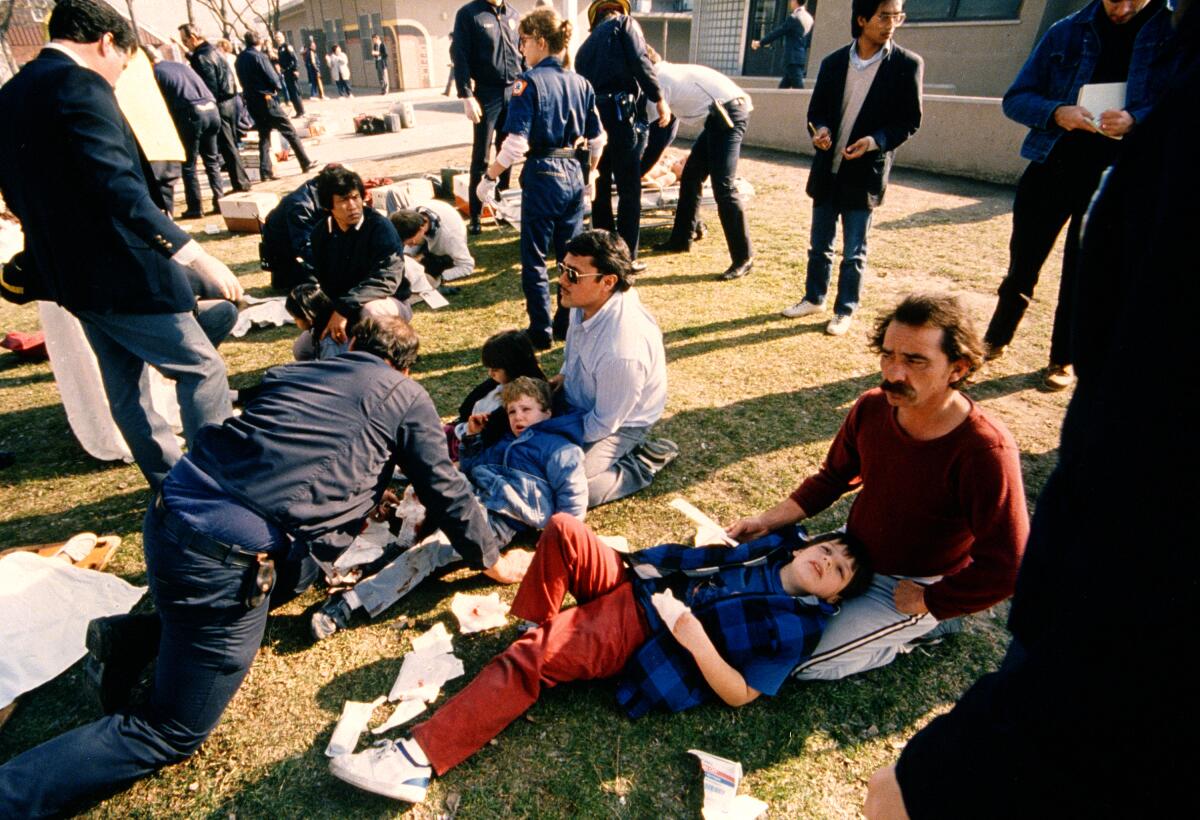

California, in fact, broke the ground for banning the weapons after the 1989 incident at a Stockton schoolyard in which a man wearing military-style fatigues, a flak vest and ear plugs used an AK-47 to fire more than 60 rounds in sweeps across a playground crowded with hundreds of children, killing five of them and wounding 30 other students and adults before shooting himself.

Such a mass shooting was a rare event at the time, and it sparked action. Congress followed in 1994 with a federal ban but compromised by including a 10-year sunset clause, allowing the ban to expire in 2004. The Benitez decision, if it is allowed to stand, would reset California back to 1989.

It’s worth noting that at the time of those bans, few people owned assault-style weapons (the industry has tried to rename them “modern sporting rifles,” which sounds much more benign). No accurate count is available because no government agency has kept track, but experts say that after the federal ban expired, production and sale of such weapons increased significantly. The rise was especially noticeable after the election of President Obama and mass killings at a Newtown, Conn., elementary school and an Aurora, Colo., movie theater — not because consumers feared home or foreign invasions, but because gun aficionados began to worry that the government was about to cut off access to the machines of mass death.

So how many of these weapons are in circulation? Again, the numbers are sketchy, but probably around 20 million nationwide, according to the National Shooting Sports Foundation, a gun industry trade group. That’s a small fraction of the estimated 350 million firearms in private hands in the U.S. That’s not very common in a nation of this size, though the Supreme Court, which set that common-use standard, hasn’t bothered to define it.

The Metropolitan Water District’s probable appointment of Hagekhalil as general manager would cement the agency’s shift toward sustainable water supplies.

It’s hard not to see the sharp increase in production and sales of assault-style weapons in the years after the Heller decision as an effort by 2nd Amendment hardliners to try to get the deadly weapons into more hands to make the spurious argument that they are now in common use. It’s galling that a federal court would buy into that reasoning, which is what Benitez has done here.

This is the same judge who tossed out a 2016 California initiative that banned the large-capacity magazines that make semi-automatic guns even deadlier, and a related initiative that requires a background check before buying ammunition (he described the “Safety for All Act of 2016” title as “a misnomer”). Both of those rulings are under appeal.

Read together, the three Benitez decisions do not come across as clear-eyed jurisprudence but, rather, as policy statements by a judge who, we note, was rated “not qualified” by the American Bar Assn. when President George W. Bush appointed him in 2003. We fully endorse Atty. Gen. Rob Bonta’s announcement that he intends to appeal Friday’s ruling too, and hope the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals overturns it.

The U.S. is an outlier among industrialized nations when it comes to the number of firearms in civilian hands and the rate at which people use them to kill others and themselves. Even the Supreme Court’s controversial 2008 Heller decision, which for the first time recognized (wrongly) an individual right to keep a gun in the home for self-defense, also said that the government has an interest in regulating firearms and that “the right secured by the Second Amendment is not unlimited.”

This is a good point at which to maintain limits. The 2nd Amendment was framed against a backdrop in which the U.S. government had no standing army, and the Founders saw the need for individuals to own guns they could bring with them when entering militia service. We don’t operate our military that way anymore, which means individuals have neither a need nor a right to possess firearms designed for battlefields.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.