Editorial: California needs standards for when schools must reopen

- Share via

Gov. Gavin Newsom must have been wincing inside last week as he said his kids were back in their private school classrooms ― part time at first, but full time later this month.

“They’re phasing back into school, and we are phasing out of our very challenging distance learning that we’ve been doing,” Newsom said, acknowledging that many other California parents have been going through that same challenge.

But many of those parents can only dream of a scenario like the governor’s. They’ve been overseeing lessons while trying to do their jobs from home. Those are the lucky ones. Other parents, whose jobs can’t be performed remotely, cannot go back to work until the kids go back to school.

Kids are frustrated, too. Lessons are typically harder to follow on a small screen than live. They miss their friends and the personal contact with teachers.

Parental pressure and downright despair are growing. It’s not an exaggeration to say that right now, the debate about whether and when to reopen public schools is second only to the question about how and when we can quell the COVID-19 pandemic itself. California legislators and mayors also have been pressing for more specific rules to get schools to open.

Newsom has created public-health standards for when schools are allowed to bring students back, and he provided funding for COVID-19 testing, safety equipment and other pandemic-related expenses, such as additional aides for smaller group learning. But beyond that, he has left school districts to decide when to reopen classrooms. And with teachers’ unions vehemently opposed in most cases, those aren’t happening even when public health officials have deemed them safe. This has to change.

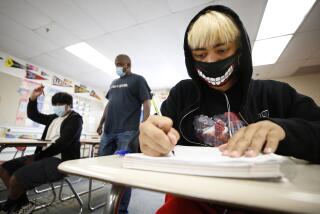

There are no readily available figures on how many schools in the state have begun reopening for in-person learning. What is known is that reopenings tend to be concentrated among private schools and more affluent areas and that low-income students of color not only are less likely to be able to attend school on campus, but also have more trouble with remote learning than white, middle-income students. The result is a quickly widening gap between the two groups and justified fears that an entire cohort of low-income students will have lower graduation rates and less chance attending a four-year college.

The remote-learning problem is obvious from information released this week by the Los Angeles Unified School District: The number of D and F grades among middle- and high-school students has increased, along with absenteeism. That’s especially true in low-income areas, where parents are often less able to help or it’s difficult to find an appropriate, quiet space to set up the computer and focus on lessons for hours at a time. Other schools across the state have seen similar problems with grades and attendance.

L.A. Unified cannot reopen campuses at this point because COVID-19 infection rates are too high and rising. But in many areas of California, schools that have been given the green light to bring students back to the classroom aren’t planning to do so before January, at the earliest.

San Juan Unified School District, in the Sacramento area, is one of those school districts. It’s also where Newsom’s children would be learning remotely right now if they were in the public-school system.

San Francisco schools also haven’t opened, though the city has lower COVID-19 rates than New York City, where students have returned to campus part time.

Granted, significant numbers of parents would not send their kids back to school if their local ones reopened tomorrow. Infection rates might rise to the point where reopening simply isn’t feasible. No one can guarantee that reopening schools won’t lead to some cases of COVID-19 transmission; they almost certainly will lead to at least a few.

But so far, in schools that have taken strong precautions, the danger seems minimal. The risk also has to be balanced against the dangers posed by keeping schools closed: Mortality rates are higher among the unemployed than people with jobs. Life expectancy is shorter among high school dropouts than those who complete their public-school education. The calculus is complicated.

Newsom and the Legislature need to design a set of standards for when schools must reopen, just as they did for when schools have to stay closed. Once it’s considered safe from a public health standard, schools should be required to open for at least some in-person learning. State intervention is the only way to overcome resistance from reluctant unions. Then, a lot more students in public schools could enjoy some of the perks that the governor’s children already have.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.