Editorial: California’s proposed new ethnic studies curriculum is jargon-filled and all-too-PC

- Share via

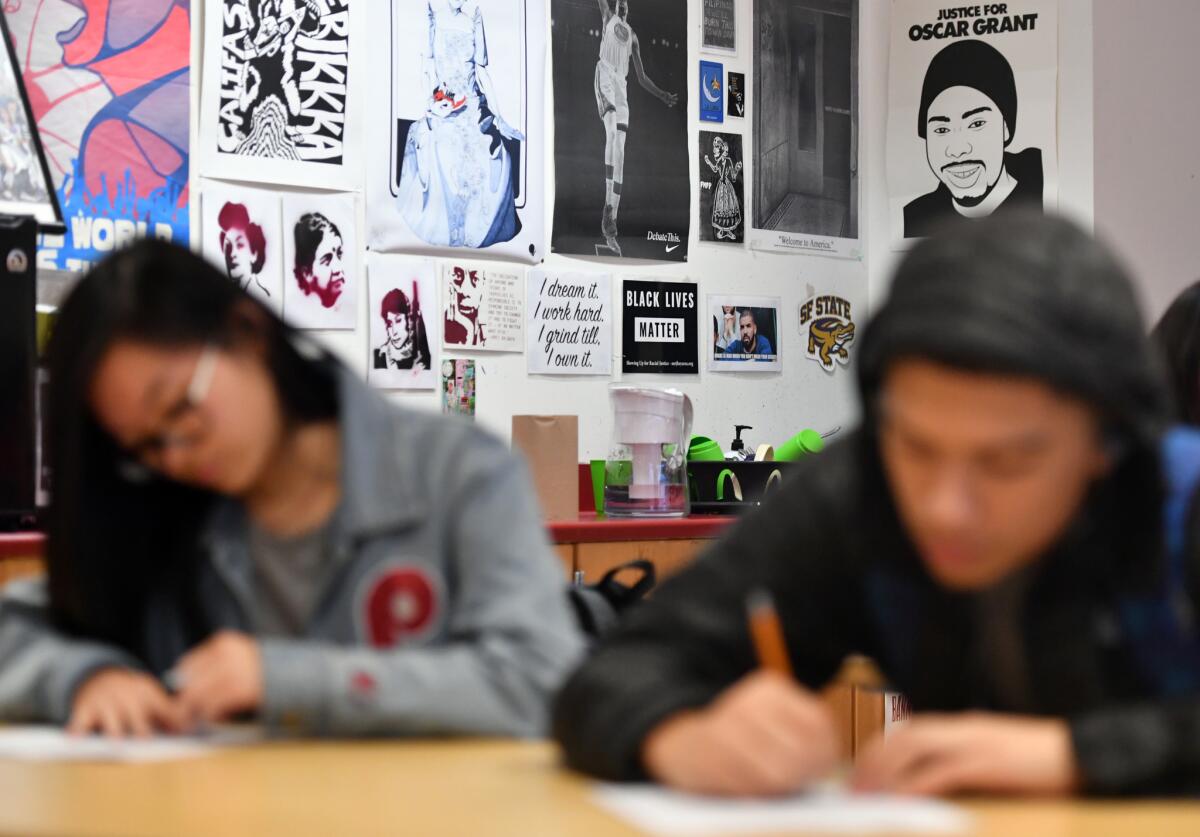

In a state as diverse as California, with all the social, historical and economic issues that arise from our rapidly changing demographics, the idea of offering an ethnic studies course in public high schools is more than a nice notion; it’s critical to imbuing students with an understanding of their own history and that of others.

A bill now working its way toward the governor’s desk would do something about that, requiring students to take an ethnic studies course for graduation, most likely replacing a semester of geography. That’s a good thing. History has for too long been told by the winners, who have often left out the unsavory and sometimes tragic aspects of the story.

But ethnic studies courses have little chance of succeeding if they don’t stem from a strong curriculum that challenges students to read, listen, gather facts, analyze those facts and think critically about the controversial issues that will naturally arise.

Unfortunately, this is precisely where the state is in danger of letting its students down. The goal of the new course is to help students learn about and engage with the history and culture of groups that have been overlooked, marginalized or subjected to “invisibility.” But a current draft of the model curriculum, drawn up by a committee of teachers and academics and headed to the State Board of Education, is an impenetrable melange of academic jargon and politically correct pronouncements. It’s hard to wade through all the references to hxrstory and womxn and misogynoir and cisheteropatriarchy.

We have no objection to a course that broadens students’ thinking about race and gender and sexuality and history and power. But too often the proposed ethnic studies curriculum feels like an exercise in groupthink, designed to proselytize and inculcate more than to inform and open minds. It talks about critical thinking but usually offers one side and one side only.

Consider this passage on assigning students to engage with their communities:

“For example, if students decide they want to advocate for voting rights for undocumented immigrant residents at the school district and city elections, they can develop arguments in favor of such a city ordinance and then plan a meeting with their city council person or school board member.”

No problem with that per se, and community engagement is a fine way to involve students in politics and civic life. But there is no mention here — or just about anywhere in the curriculum — of students who might dare to disagree with the party line. In this case, for instance, some students might think that the right to vote in mayoral and city council elections is the prerogative of citizens, not noncitizens (that’s not a right-wing idea, is it?), and they might want to meet with the school district about that. Chances are, with a curriculum like this one, they’d be afraid to even mention it.

Similarly, there’s a suggested list of social movements that students might research — but here again, the curriculum feels awfully one-sided. There’s nothing wrong with students studying the Black Panther Party or the Third World Liberation Front or the Occupy Movement or the Palestinian-led BDS movement. But what happened to studying a range of ideas, reflecting a variety of ideologies and perspectives, and having students take sides, dispute and debate those ideas, honing their research and thinking in the process, and ultimately deciding for themselves? This curriculum feels like it is more about imposing predigested political views on students than about widening their perspectives.

Among other things, the model curriculum lists capitalism with white supremacy and racism as “forms of power and oppression.” OK, but shouldn’t students also hear arguments that capitalism has allowed for an expansion over time of the middle class, or even from those who believe in a laissez-faire, sink-or-swim economy.

And isn’t it possible that some students won’t agree with the curriculum’s assertion that BDS is a social movement “whose aim is to achieve freedom through equal rights and justice.” Does that perhaps merit further debate?

School districts will be free to pick and choose from the model curriculum that is eventually approved, but they would probably rely heavily on the approved document. Though the draft, which is open to public comment until Aug. 15, offers many interesting ideas, it is in bad need of an overhaul. The final curriculum should emphasize the deep, disturbing and complex facts of racial and ethnic history, respecting differences of opinion, and encouraging open discussion on an often difficult subject.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.