Op-Ed: How the 1968 Democratic convention fomented today’s culture wars

- Share via

Fifty years ago today, one of the fiercest battles of the 1960s took place not in the jungles of Vietnam, but on the streets of Chicago.

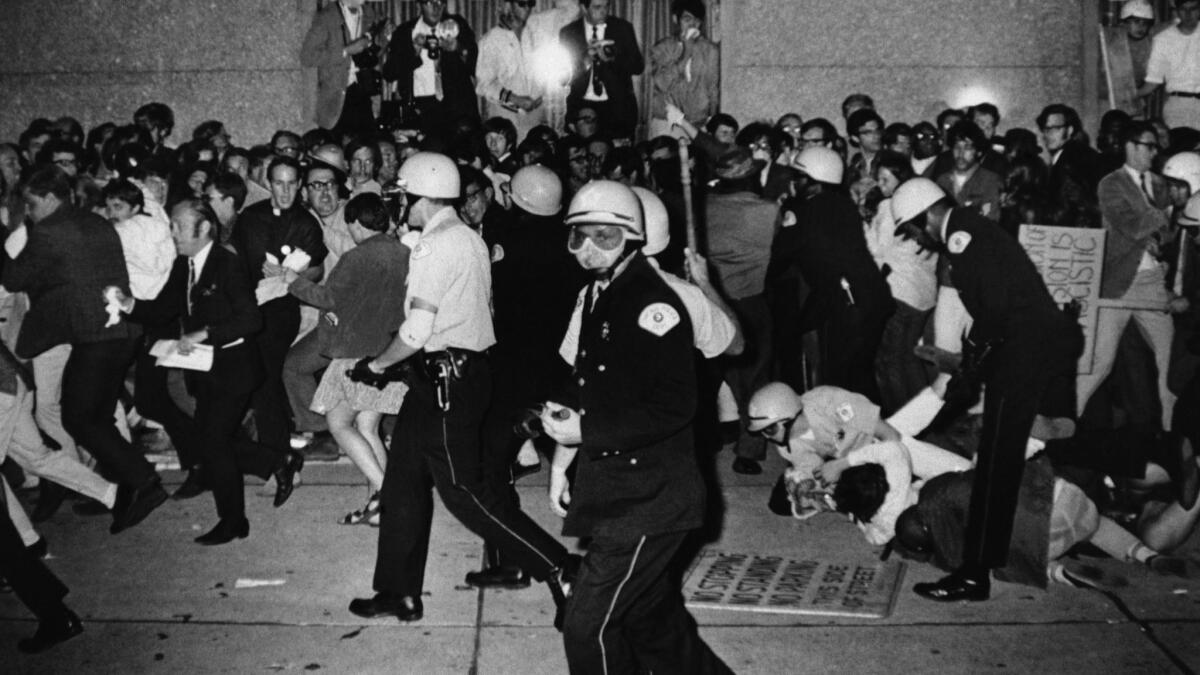

On Day 3 of the 1968 Democratic National Convention, police clashed violently with antiwar demonstrators before a rapt television audience of 90 million Americans. The Battle of Michigan Avenue, as the episode came to be known, in many ways prefigured the culture wars that dominate American politics today.

Protesters had converged on Chicago because the Democratic Party was set to disregard the antiwar presidential candidacies of Minnesota Sen. Eugene McCarthy and the late Robert Kennedy by nominating Vice President Hubert Humphrey, who supported the Vietnam War.

But there was more to the Chicago conflict than Vietnam. Old-guard Democrats viewed the white working class as the backbone of the country and protesters as ungrateful interlopers who didn’t appreciate what made America great. Protesters saw the white working class and its hawkish, insular attitudes as part of the problem.

The violence percolated over the first two days of the convention, and protesters certainly deserved some of the blame for it. They hurled rocks, bottles and garbage at police, as well as insults such as “fascist pig,” “oink, oink” and “seig heil.” But their actions paled in comparison to the violence let loose by police.

The Battle of Michigan Avenue foreshadowed the America we inhabit today: divided, distrustful, aggrieved and entrenched in opposing cultural camps.

According to the Walker Report, an official investigation of the protests conducted by a special commission, the police unleashed “unrestrained and indiscriminate” terror throughout the week, bloodying not just demonstrators but also medics, seminarians, journalists and other bystanders. The conflict culminated in a 17-minute melee outside the main convention hotel, the Conrad Hilton, just before the Democrats were to nominate Humphrey.

Wielding billy clubs, rifle butts, tear gas and mace, police overtook the demonstrators, some shouting “kill, kill” as they advanced. At one point, police pushed spectators through a plate-glass window, “sending screaming middle-aged women and children backward through the broken shards of glass,” as the New York Times later reported.

Some demonstrators fought back with firecrackers, rocks or other makeshift weapons, but the protesters’ main defense was to chant a refrain: “The whole world is watching!” The Walker Report ultimately concluded that the event was “a police riot.”

It wasn’t long after the violence ended that a larger battle erupted over its meaning. Protesters thought they had unmasked America as a police state. In a speech to the convention, Connecticut Sen. Abraham Ribicoff immortalized the police violence as “Gestapo tactics in the streets of Chicago.”

The press condemned Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley for giving his officers free rein to brutalize demonstrators. “The pictures and sound of the Chicago Police Department speak for themselves,” CBS News President Richard Salant said at the time.

But a large majority of Americans disagreed. In a poll conducted shortly after the convention, 71% said that the police measures were justified and 57% rejected claims that the police used excessive force.

Millions of Americans simply couldn’t believe that the police — who defended their communities and reflected their values and way of life — could act in the manner they saw on TV. They didn’t call it “fake news,” but many Americans thought it was.

Newspapers were inundated with letters saying that the TV news “cannot be trusted” and accusing the press of giving radicals a voice while “totally ignoring responsible Americans.” TV networks also heard from viewers directly. “We got thousands of calls from people saying they didn’t believe their eyes, accusing us of hiring cops to beat up kids,” said the Washington bureau chief for CBS News, Bill Small.

To some public officials, the press was as culpable and disdainful as the protesters. “The intellectuals of America hate Richard J. Daley because he was elected by the people — unlike Walter Cronkite,” said the director of public information for Chicago’s police. Daley himself derided “commentators and columnists,” blamed the media for inciting the violence and called the news coverage “distorted and twisted.”

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute from L.A. Times Opinion »

Perhaps taking their cues from Daley, the police had singled out reporters and photojournalists for assault that week. NBC News anchor David Brinkley said: “They’ve had their heads smashed, they’ve been sprayed with tear gas, their cameras grabbed and destroyed.” Brinkley’s partner, Chet Huntley, declared: “The news profession in this city is now under assault by the Chicago police.” In total, according to the Walker Report, 63 journalists were physically attacked by the police.

Nevertheless, it was the police who earned the public’s sympathy. The police had become, as the columnist Joseph Kraft wrote, “part of an embattled social group.”

The Battle of Michigan Avenue foreshadowed the America we inhabit today: divided, distrustful, aggrieved and entrenched in opposing cultural camps and world views. Then, as now, authorities could attack the free press, and millions of Americans simply refused to believe what they saw.

Leonard Steinhorn is a professor of communication and history at American University.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.