Op-Ed: Barbara Ehrenreich: White working-class longevity drops along with white privilege

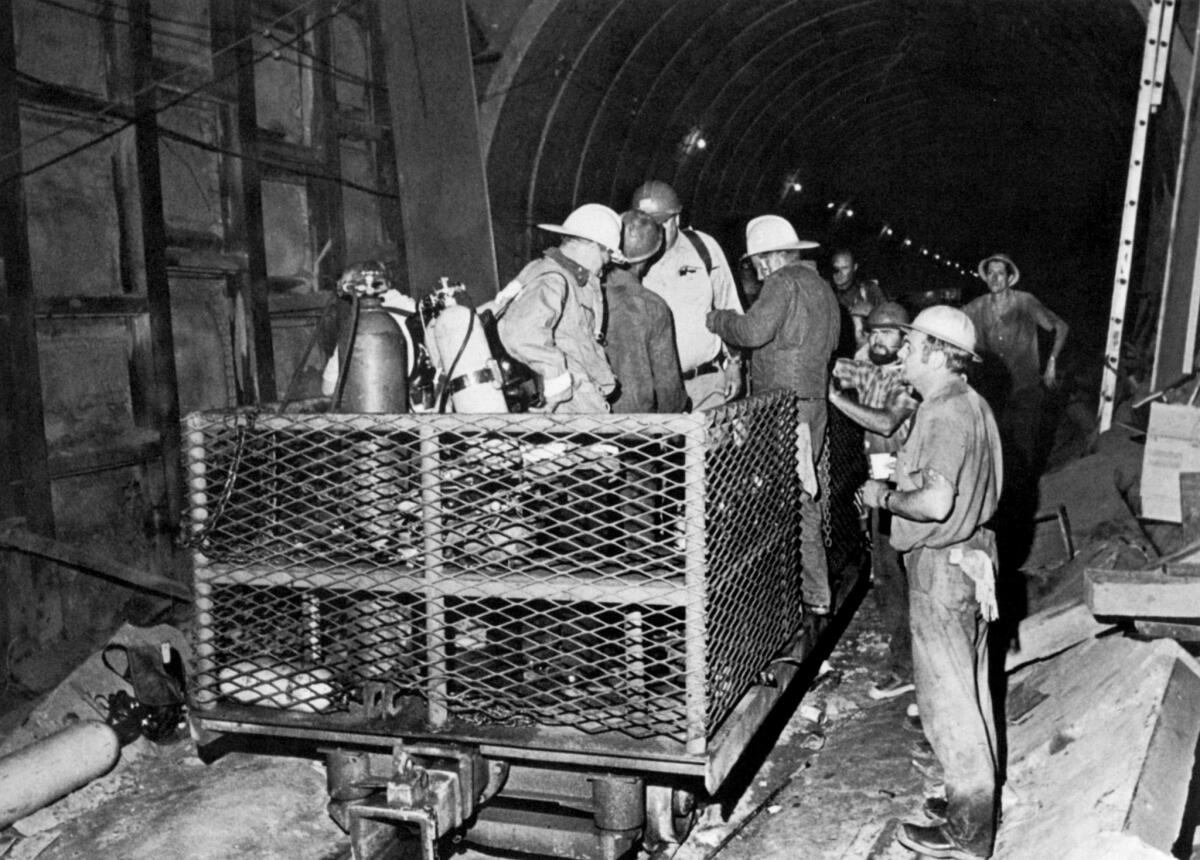

Workers and firemen in a Metropolitan Water District tunnel in Sylmar in 1971.

- Share via

For almost a century, there was a comforting American narrative that went like this: Advances in nutrition and medical care would guarantee longer lives for all. Recently published research, however, shows that members of the white working class, ages 45 to 54, are dying at an immoderate rate. In the last four years, the life span gap between poor white men and wealthier ones has widened by up to four years.

This was not supposed to happen. Especially not to white people, who in relation to people of color have long had the advantage of higher earnings, better access to healthcare, safer neighborhoods and, of course, freedom from the daily insults and harms inflicted on the darker-skinned. There has long been a racial gap in longevity — 5.3 years between white and black men; 3.8 between white and black women — though, hardly noticed, it has been narrowing since the mid-1990s. But now it is whites who are dying off in unexpectedly large numbers in middle age, deaths accounted for by suicide, alcoholism and drug (usually opiate) addiction.

As blacks have made gains, in the de jure sense, whites have lost ground economically. As a result, the “psychological wage” awarded to white people has been shrinking.

There may be some practical reasons why some white people have gotten more efficient at killing themselves. For one thing, whites are more likely than blacks to be gun owners, and white men favor gunshots as a means of suicide. For another, doctors, undoubtedly acting in part on stereotypes of nonwhites as drug addicts, may be more likely to prescribe powerful opiate painkillers to whites than to people of color when manual labor — from waitressing to construction work — wears down knees, backs and rotator cuffs.

But something more profound is going on here too. As New York Times columnist Paul Krugman puts it, the “diseases” leading to excess white working-class deaths are those of “despair.”

I grew up in an America where a man with a strong back — and better yet, a strong union — could reasonably expect to support a family without a college degree. In 2015, those jobs are long gone, leaving only the kind of work once relegated to women and people of color. Those in the bottom 20% of white income distribution face material circumstances like those long familiar to poor blacks, including erratic employment and crowded, hazardous living spaces.

White privilege was never, however, simply a matter of economic advantage. As W.E.B. Du Bois wrote in 1935, “It must be remembered that the white group of laborers, while they received a low wage, were compensated in part by a sort of public and psychological wage.” He was talking about admission to public schools, spaces and functions. Today, at least legally speaking, all of that is open to all. But as blacks have made gains, in the de jure sense, whites have lost ground economically. As a result, the “psychological wage” awarded to white people has been shrinking.

For most of American history, government could be counted on to maintain white power and privilege by enforcing slavery and later segregation. When the federal government finally weighed in on the side of desegregation, working-class whites were left to defend their diminishing privilege.

The culture, too, has inched toward racial equality. If the stock moronic derogatory image of the early 20th century “Negro” was the minstrel, the role of rural simpleton has been taken over in this century by “Duck Dynasty” and “Here Comes Honey Boo Boo.” It’s not easy to maintain the usual sense of white superiority when the entertainment world is squeezing laughs from the contrast between savvy blacks and rural white bumpkins, as in the new Tina Fey comedy “Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt.”

Then of course there was the election of the first black president. Among some white, native-born Americans there was talk of “taking our country back.” The more affluent ones formed the tea party; less affluent ones could choose to affix Confederate flag decals to their trucks.

All of this means that the maintenance of white privilege, especially among the least privileged whites, has become more difficult and so, for some, more urgent than ever, right down to perpetrating the micro-aggressions that roil college campuses, the racial slurs yelled from pickup trucks or, at a deadly extreme, the shooting up of a black church renowned for its efforts in the Civil Rights era. Dylann Roof, the Charleston, S.C., killer who did just that, was a jobless high school dropout and reportedly a heavy user of alcohol and opiates. Even without a death sentence for the killings hanging over him, Roof was surely headed toward an early demise.

Although there is no medical evidence that racism is toxic to those who express it — after all, generations of wealthy slave owners survived quite nicely — the combination of downward mobility and racial resentment may be a potent invitation to the kind of despair that leads to an increase in white working-class deaths, to suicide in one form or another, whether by gunshots or drugs. You can’t break a glass ceiling if you’re standing on ice.

It may be easy to feel righteous disgust for lower-class white racism and no less easy to feel noble for acknowledging the economic and psychological misery of the white working class. But Americans higher up the ladder are in trouble too, with diminishing prospects facing adults and the young. Whole professions have fallen on hard times, from college teaching to journalism and the law. One of the worst mistakes this relative elite could make is to try to pump up its own pride by hating on those — of any color or ethnicity — who are on the downward slope and falling even faster.

Barbara Ehrenreich is the founding editor of the Economic Hardship Reporting Project. A longer version of this essay appears at TomDispatch.com.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.