Editorial: Was this man sentenced to death because he is gay? The Supreme Court should take up that question

- Share via

Charles Rhines was burglarizing a Rapid City, S.D., doughnut shop from which he had been fired a month earlier when a worker walked in. Rhines stabbed the man to death, and a jury convicted him in 1993 of first-degree murder.

When called upon to recommend death or life in prison, though, the jurors had a lot of unusual questions. If they sentenced Rhines to life in prison, they asked the judge during deliberations, would he be able to mix with the rest of the prisoners, “create a group of followers or admirers,” have access to “new and/or young men jailed for lesser crimes” or be housed alone or with a roommate?

Why did they ask such questions? Rhines is gay, and, as one of the jurors later said, they wondered whether if in sentencing him to life in prison “we’d be sending him where he wants to go.” So they sentenced him to death instead.

Note that the life-or-death sentencing decision doesn’t appear to have been based on the particulars of the crime, but on who Rhines is and on jurors’ prejudices about gay men — beliefs that only one of the 12 had acknowledged during jury selection (the biased juror promised to set those views aside). Yet a juror later recalled “lots of discussion of homosexuality” in the jury room. “There was a lot of disgust.”

Enter the Fray: First takes on the news of the minute »

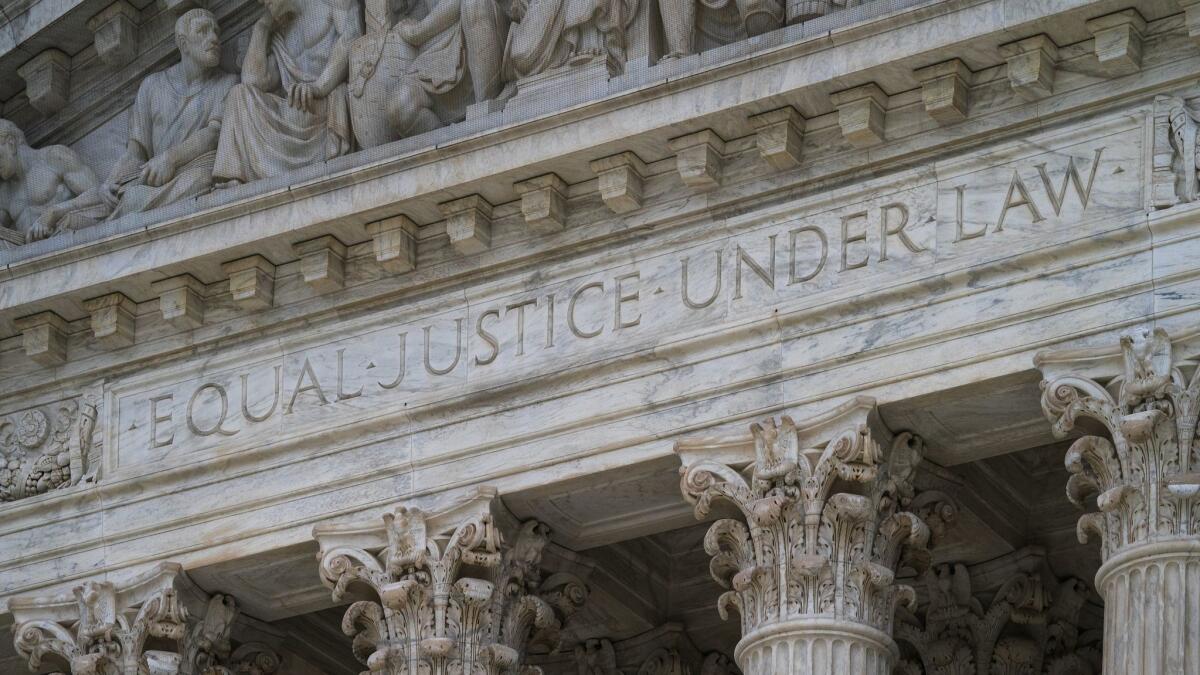

Rhines’ attorneys did not discover much of this evidence until after his appeals had been heard and rejected by federal courts. On Friday, the Supreme Court will consider whether to take his case, reverse those rulings and give Rhines a chance to present the new evidence he’s found about anti-gay statements in the jury room. The court should do all of that. That Rhines is fighting the imposition of a death sentence, rather than the addition of a few years to a prison term, makes the repercussions of possible discrimination all the more outrageous.

The Supreme Court has ruled in previous cases that evidence of racial prejudice influencing a jury’s decision can be used by a defendant to appeal for a new trial, even if the evidence is discovered after the defendant was convicted. Rhines argues that the same logic should apply to decisions weighted by anti-gay bias. We agree. It could turn out after proper appellate hearings that the discussions were not as vile as Rhines portrays them, or that prejudice did not, in fact, weigh on the sentencing recommendation. But justice requires that Rhines at least be able to have a court review whether he was, indeed, sentenced to death not because of what he did, but because of who he is.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion or Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.