Editorial: Sorry, Italy, the ‘Getty Bronze’ belongs in L.A.

- Share via

For decades, the Getty Museum and other art institutions in the United States have struggled to deal with the tainted provenance of many of their most valuable antiquities. The Getty, the world’s richest museum, has returned more than 40 pieces to Greece and Italy since 2007 because of questions about how or where or under what circumstances they were acquired. It has instituted stricter acquisition policies that have become a model for a more conscientious era of art collecting.

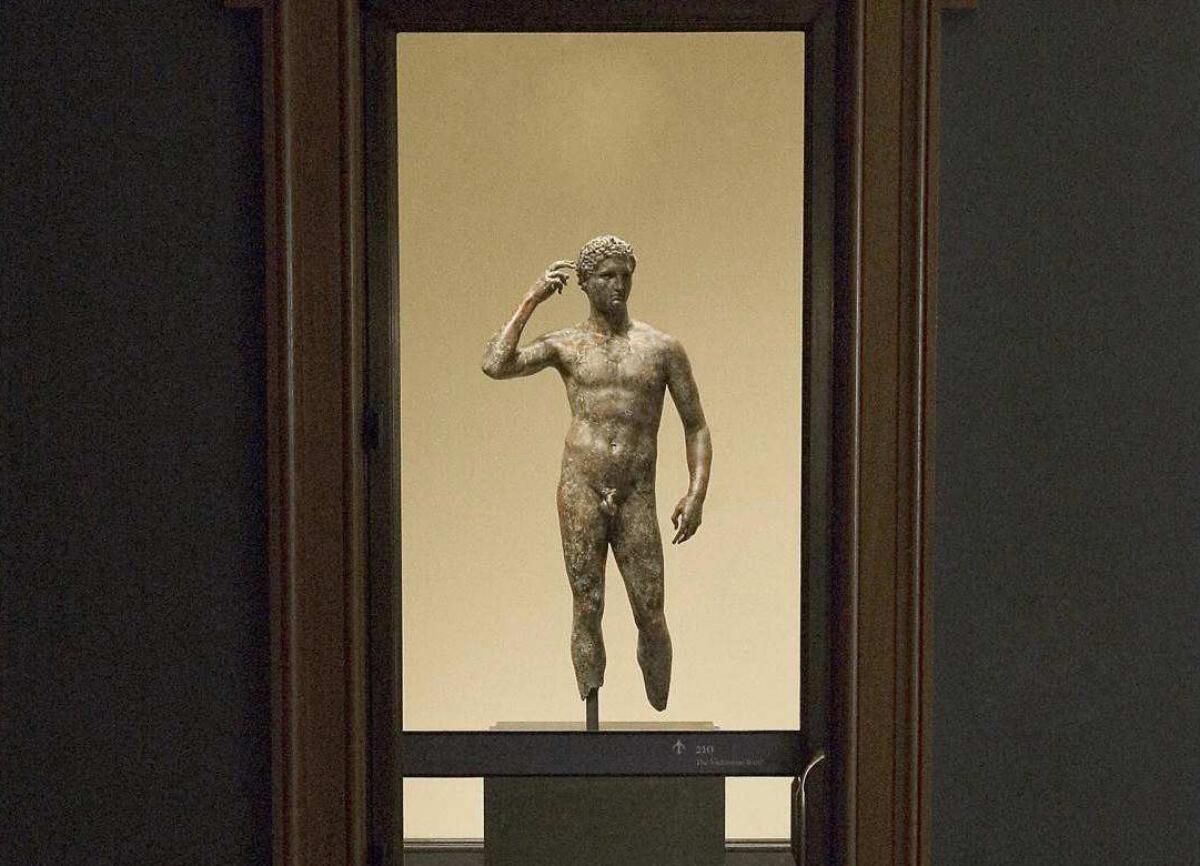

That hasn’t stopped disputes over pieces that remain in the Getty collection. One of the longest-running battles centers on a life-size bronze statue known as the “Victorious Youth,” an ancient masterpiece that commands its own humidity-controlled room at the Getty Villa. The trustees of the museum bought it from a German art dealer in 1977 for $3.95 million and put it on display the next year. An intact sculpture dating to the 2nd or 3rd century BC, its value today is unknown; museum officials say only that it is priceless.

The statue, also known as the “Getty Bronze,” is believed to be Greek in origin, but it was discovered by Italian fishermen in international waters off the coast of Italy in 1964. Ever since they brought it ashore, hid it and then sold it, Italian officials have periodically tried to get it back. The Getty has contended that it was not discovered in Italian waters, that it was purchased legally and that it has no archaeological significance to Italy. An Italian court is expected to rule Wednesday on whether the Getty should give it up.

It should not. This is not another “Aphrodite” — the marquee Getty statue that was illegally excavated in Sicily and smuggled out, and that the Getty sent back in 2010.

Few cases of contested art are simple, and this one is particularly convoluted. By most accounts, the fishermen who happened upon the bronze and brought it to Italy never declared it to government authorities and sold it secretly before it was smuggled out of the country. But the Italian courts were never able to prove those buyers were taking possession of “stolen property” because it hadn’t actually been stolen and hadn’t come from Italian waters.

In 2007, a regional court in Italy rejected a prosecutor’s order to have the bronze returned. But another prosecutor successfully persuaded a judge in 2010 to order forfeiture. The Getty has appealed twice to the Court of Cassation, which is expected to rule Wednesday.

Since 2001 there has been an agreement between the U.S. and several countries, including Italy, requiring the U.S. to return illegally exported works. But the bronze left Italy long before that law took effect.

The bronze spent the vast majority of its first 2,000 years deep in the ocean. Its longest home since then has been the Getty. That is where it should stay.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.