Natasha Richardson dies at 45

- Share via

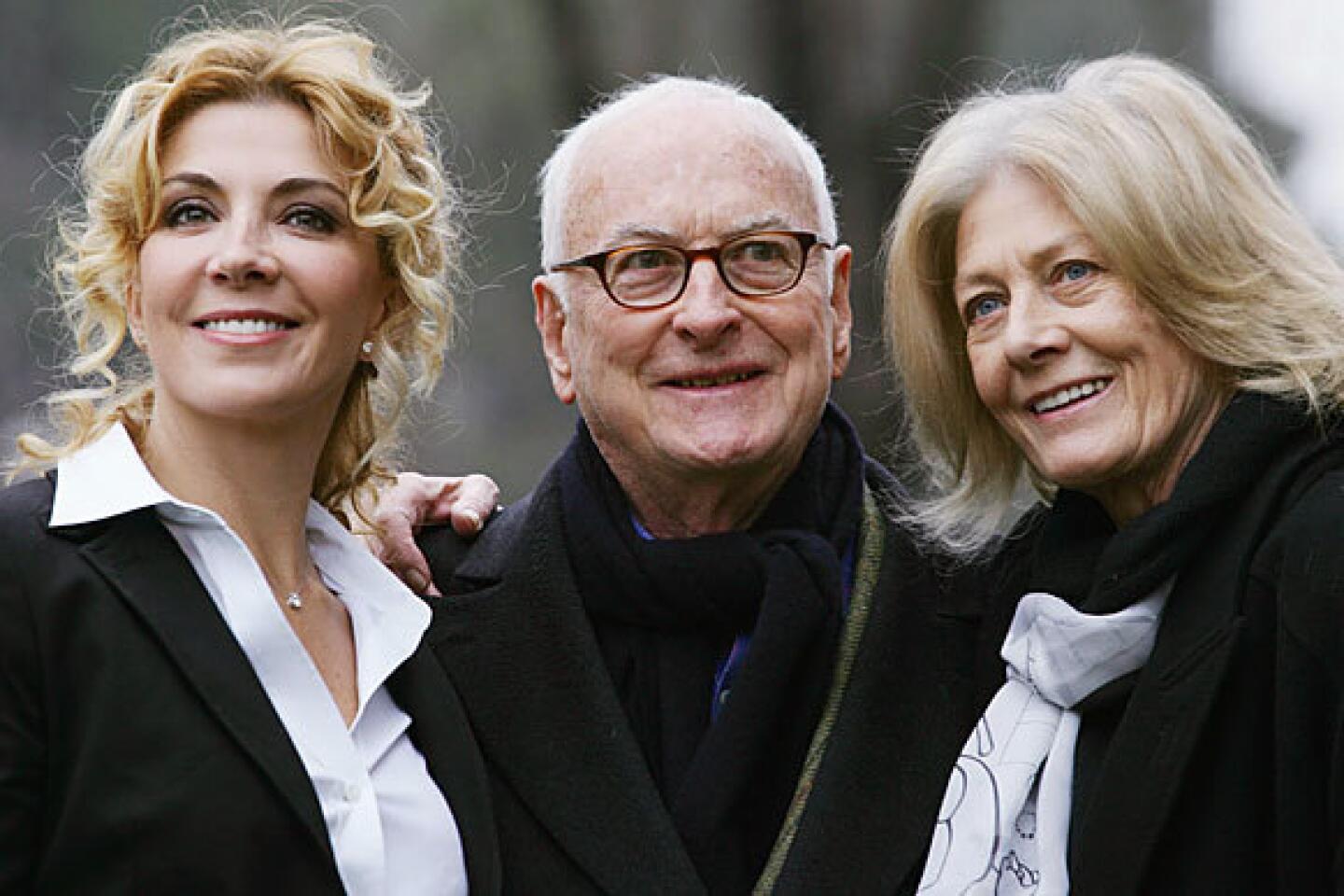

Natasha Richardson, the luminous British actress from one of the world’s great acting families, whose performances ranged from the high-brow drama “The Handmaid’s Tale” to the lightweight comedy “The Parent Trap” and the Tony-winning Broadway production of “Cabaret,” died Wednesday. She was 45.

The wife of “Schindler’s List” actor Liam Neeson and daughter of actress Vanessa Redgrave and the late film director Tony Richardson died at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York. The cause of death was not announced, but she had been hospitalized after suffering a devastating brain injury while skiing Monday.

“Liam Neeson, his sons and the entire family are shocked and devastated by the tragic death of their beloved Natasha,” said a statement released by publicist Alan Nierob. “They are profoundly grateful for the support, love and prayers of everyone, and ask for privacy during this very difficult time.”

Richardson was injured at Mont Tremblant, a luxury resort in Canada. The actress was taking a lesson on a beginner’s run near the bottom of the ski area and was not wearing a helmet when she had what first appeared to be a minor accident.

She initially reported that she was well, but soon started to complain of a headache. Hours after the fall, the star of a number of acclaimed stage plays -- including “Anna Christie,” “A Streetcar Named Desire” and “Closer” -- slipped into unconsciousness, and she was transported Tuesday from a Montreal hospital back to New York, where she was surrounded by family and friends.

The actress’ most recent film credits came in last year’s “Wild Child” opposite Emma Roberts and 2007’s “Evening” with Meryl Streep, Claire Danes and Redgrave. The “Evening” part was one of a number of recent roles Richardson had had in productions with her closest relatives. On television, she appeared as a guest judge on the just-concluded season of the cooking show “Top Chef.”

Richardson was born in London on May 11, 1963. In addition to Redgrave, other actors in her family include sister Joely Richardson, a star of the television series “Nip/Tuck,” and aunt Lynn Redgrave, whose film credits include “Georgy Girl” and “Gods and Monsters.” Richardson’s grandfather was legendary Shakespearean actor Michael Redgrave.

Her father was an acclaimed writer, director and producer who won the directing and best picture Oscar for 1963’s “Tom Jones.” Tony Richardson, who died in 1991 at age 63, also directed “Look Back in Anger” and “A Taste of Honey.”

The actress’ 72-year-old mother, who won the supporting actress Academy Award for 1977’s “Julia,” still acts in theater and film.

Just before the skiing accident, Richardson was considering a Broadway revival of Stephen Sondheim’s “A Little Night Music” with her mother, after a highly praised one-night January staging at New York’s Studio 54.

Although Richardson may have come from royal show business blood, she did not try to use her ancestry to advance her career, but rather saw her family’s creative business as something of a classroom.

“I know the pressures of being the daughter of a great actress,” Richardson said in a 2005 interview with London’s Independent newspaper. “But it’s inspiring. You learn so much that other people don’t get to learn until later on. My father being a director, I [learned] a real work ethic. You think: ‘One day, I’d like to be as good as that.’ But when I was starting out professionally, I had a level of attention put on me that I didn’t deserve or wasn’t ready for. And it was hard, particularly in England, to make my way.”

Richardson trained at London’s Central School of Speech and Drama, hiding her family connections, and subsequently picked up minor parts in little-known theater and television productions. In 1985, she made her West End debut, playing the troubled young actress Nina in Anton Chekhov’s “The Seagull.” A year later, Richardson was cast in her first prominent movie role, starring in director Ken Russell’s “Gothic” as “Frankenstein” author Mary Shelley.

A variety of more prominent movie and stage roles followed, but Richardson often gravitated toward artier film productions, with mainstream movies more exception than rule. Despite her British roots, she often played iconic American characters -- including Patty Hearst (in a movie of the same name), Blanche DuBois in Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” and the title role in Eugene O’Neill’s “Anna Christie.”

With a gravelly, seductive voice (once compared to a combination of honey and iron filings), Richardson was frequently willing to play emotionally vulnerable roles. “I just feel for her,” she told the Times in 1993 about Anna Christie. “Her anger and her loneliness and her pain.”

Richardson’s movie choices in 1990 exemplified her creative taste. That year, she starred in “The Comfort of Strangers,” a drama about a couple (Richardson and Rupert Everett) trying to repair a failing relationship, and “The Handmaid’s Tale,” an adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s novel about a future theocracy. Hinting at her growing interest in theater, the screenplays for both movies were written by the playwright Harold Pinter.

Richardson made her Broadway debut in 1993, playing opposite Neeson in “Anna Christie.” She was married to producer Robert Fox at the time; they divorced that year, and she married Neeson in 1994. The couple had two sons together, Micheal and Daniel, and Richardson left acting for three years when they were born.

“I have a famous mother, and it took me years to get over that,” she once told London’s Mirror. “Now I have this really famous husband. I definitely feel a loss of confidence. Perhaps that’s partly why I love living in New York, being free of all that family baggage, being open to all sorts of possibilities.”

Richardson continued to appear in movies, with the highest-profile roles coming in the 1998 remake of “The Parent Trap” opposite Lindsay Lohan and Dennis Quaid, and 2002’s romantic comedy “Maid in Manhattan” with Jennifer Lopez.

But Richardson’s most distinguished work was delivered inside London and New York’s theaters: as Sally Bowles in director Sam Mendes’ revival of “Cabaret” in 1998 (for which she won a Tony and a Drama Desk award); a year later in the Broadway production of Patrick Marber’s “Closer”; reprising a role once played by her mother in the 2003 London production of Henrik Ibsen’s “The Lady From the Sea”; and 2005’s Broadway revival of “A Streetcar Named Desire.”

Los Angeles Times reviewer Laurie Winer said of her “Cabaret” performance: “Wearing a slip, torn stockings and dirty hair, she dazzles simply by lifting her huge, wondrous eyes -- lined in yesterday’s stained makeup -- tearfully to the theater’s low balcony.”

In his Times review of “Closer,” Michael Phillips wrote: “On stage, the unglamorously glamorous Natasha Richardson has a wonderful way of asking a question as if it were a statement, as if the question mark were extraneous and obvious. She does that in a way that reveals, warily, a bit of her character’s insides.”

Richardson was often drawn to stories that illuminated a character’s deepest -- and sometimes darkest -- secrets.

In 2005’s “Asylum,” a movie she spent seven years getting made (taking an associate producer credit to help move it forward), Richardson played Stella, the unhappy wife of a psychiatric hospital doctor. The film, in which Richardson’s character is drawn to a mental patient, failed to attract an audience in the United States, but it did bring the actress several British honors.

“One of the reasons I related to Stella, and why I think a lot of women relate to her, is that we’ve all had moments in life when you look at the edge of the abyss and think, ‘Am I going to throw caution to the wind?’ ” she said in a 2006 interview with London’s Evening Standard. “Most of us decide to pull in the reins. Stella doesn’t.”

In addition to the revival of “A Little Night Music,” Richardson in recent years performed in several other projects with her closest relatives. In the 2005 film “The White Countess” she appeared opposite Lynn and Vanessa Redgrave. Two years later, she and her mother played a mother and daughter in “Evening.”

Times staff writer Mike Boehm contributed to this report.

An appreciationBorn into theatrical royalty, she refused to be burdened by her heritage. CALENDAR, D1

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.