Rep. Henry Waxman to retire after four decades in Congress

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Rep. Henry A. Waxman, one of the nation’s most influential liberal lawmakers for nearly four decades, will retire from his Westside seat this year, closing a career in which he successfully championed laws to clean the country’s air, regulate cigarettes and steadily expand healthcare coverage for the poor.

His retirement, which set off a political scramble among potential replacements, was the latest of a series of departures that are remaking the state’s long-stable congressional delegation. It also brings an end to an era of Democratic political activism that opened when a huge class of Democrats, including Waxman, entered the House in the post-Watergate election of 1974.

Waxman and his California colleague, Rep. George Miller (D-Martinez), who announced his retirement earlier this year, were the last two members of the 1974 class to have served in the House ever since.

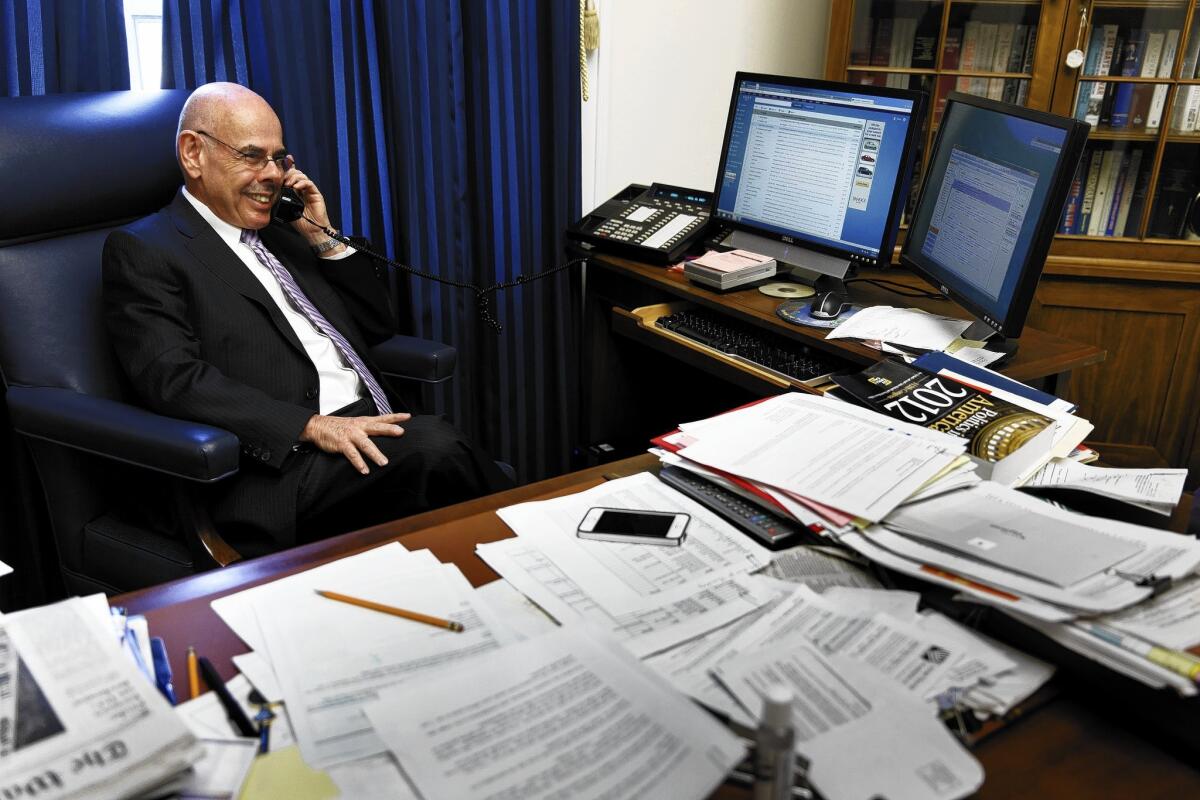

His longevity in office, coupled with his willingness to take a long view on legislation, gave Waxman the chance to assemble a train of victories few lawmakers could match. The walls of his Capitol Hill office are covered with 18 framed copies of bills he sponsored and the pens that Democratic and Republican presidents used to sign them into law. Among them are several measures which, standing by themselves, would have capped the careers of other lawmakers.

In an interview, Waxman, 74, said he had decided, simply, that the time had come to do something else.

“At the end of this year, I would have been in Congress for 40 years,” he said. “If there is a time for me to move on to another chapter in my life, I think this is the time to do it.”

Bald, mustachioed and 5-foot-5, Waxman was a hero to many liberals who hailed his stands on healthcare and the environment. Many conservatives denounced him as an implacable backer of expanded government and a fierce partisan.

But although he was the political son of ardent New Deal Democrats and represented one of the country’s most left-leaning districts, Waxman carefully steered clear of ideological dead ends. He achieved some of his biggest victories under Republican presidents, in part because of a willingness to compromise and tactical shrewdness.

In legislative efforts, some of which persisted for decades, he outlasted and often outmaneuvered opponents. When clean air rules came under attack during the Reagan administration, for example, he thwarted one assault on the law by offering 600 amendments, which he wheeled into a committee room in a shopping cart.

Then, his campaign on the issue shifted to offense, leading to the Clean Air Act amendments of 1990, which greatly strengthened pollution controls. Strongly opposed by the automobile and oil industries until it was signed by President George H.W. Bush, the law is credited for leading to dramatic improvements in air quality in Los Angeles and other heavily polluted cities.

Similarly, Waxman won the first of a series of expansions of Medicaid during President Reagan’s tenure, incrementally building coverage for the poor, then protecting his advances from budget cuts. In the late 1990s, under President Clinton, he pushed to create what became the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which gave children from lower-income families access to publicly subsidized coverage.

In 2009, Waxman played a leading role in the campaign to pass President Obama’s healthcare law as head of a key committee and one of the chief lieutenants for then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-San Francisco).

Though he personally supported a single-payer system, Waxman made his pragmatic case to fellow liberals, helping rally them to the law. At key points, he worked to defuse tensions with more conservative Democrats, who several times threatened to scuttle the legislation.

Passage of the law fulfilled “one of my lifelong dreams” by guaranteeing access to healthcare coverage for Americans, Waxman said in a statement announcing his retirement plans. Indeed, establishing guaranteed national health insurance was one of the pledges of his first congressional campaign.

Obama praised Waxman in a statement in which he called him “one of the most accomplished legislators of his or any era.”

“Thanks to Henry’s leadership, Americans breathe cleaner air, drink cleaner water, eat safer food, purchase safer products, and, finally, have access to quality, affordable healthcare,” Obama said.

The kind of clout Waxman exercised is unlikely to be replicated any time soon, in part because of changes in the way the House works that have increased the power of party leaders at the expense of committee chairs, said John J. Pitney Jr., professor of American politics at Claremont McKenna College and a former Republican official.

“There probably won’t be another Henry Waxman any time in the near future,” Pitney said. “For years to come, students in political science classes will be reading about his leadership” on issues such as tobacco control. “There aren’t many members of Congress who leave that kind of footprint.”

In his statement, Waxman said that although he has been frustrated at times, “I am not leaving out of frustration with Congress. Even in today’s environment, there are opportunities to make real progress.”

Still, he complained about the “extremism of the tea party Republicans,” and said he was “embarrassed that the greatest legislative body in the world too often operates in a partisan intellectual vacuum, denying science, refusing to listen to experts and ignoring facts,” an apparent reference to his difficulty in getting climate-change legislation to the president’s desk.

He expressed confidence that he would have won reelection had he run again — something most political handicappers agree on — but lamented the amount of time that he would spend campaigning and fundraising.

In 2012, Waxman survived an $8-million challenge from a deep-pocketed independent candidate in a newly drawn district that brought him his first real contest in years. He won with 54% of the vote.

Waxman’s departure will significantly weaken California’s clout on Capitol Hill, where seniority still matters. He is the House’s sixth-most senior member and the fourth veteran California congressman to head for the exits this year, along with Miller and Republican Reps. Howard “Buck” McKeon of Santa Clarita, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, and John Campbell of Irvine.

His announcement, along with Miller’s, renewed speculation about whether Pelosi would also decide to leave. The Democratic House leader moved quickly to scotch such talk.

“I’m running. I’ve already started the paperwork process. My work is not finished,” she said in a statement.

Among Waxman’s specialties were high-profile hearings that drew headlines as well as protests from officials of the Republican administrations he pilloried.

The sessions that attracted the most public attention came in 1994, when Waxman summoned the heads of the nation’s tobacco companies to a televised hearing. Their public testimony, in which they claimed not to believe cigarettes were addictive, became a “turning point in our national history,” Waxman later wrote in a book with Joshua Green, “The Waxman Report: How Congress Really Works.”

Fifteen years later, Obama, who had had his own struggles to quit smoking, cited the hearing when he signed legislation cosponsored by Waxman that gave the federal government new authority to regulate tobacco.

Waxman’s toughness extended to Democratic rivals whom he was willing to elbow out of his way.

Early on, he won a key subcommittee chairmanship with jurisdiction over health laws, pushing aside a more senior lawmaker with the help of freshman lawmakers for whom he had raised campaign funds in his wealthy, politically active district.

In 2008, with a Democrat headed for the White House and a long-sought national health insurance law within reach, Waxman took the chairmanship of the House Energy and Commerce Committee away from veteran Rep. John D. Dingell (D-Mich.), the chamber’s longest-serving Democrat.

Waxman and Dingell, who represents a Detroit-area district heavy with automakers, had long fought over clean-air legislation, but in this battle, advocates of healthcare reform pointed to Dingell’s age, saying he lacked the stamina for what was certain to be a long and complex fight.

In the Democratic caucus that decided on the chairmanship, Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.) delivered a speech illustrating the breadth of Waxman’s achievements.

Holding up a bag of potato chips, Schakowsky said, “There is a nutrition label on the bag that we all know and take for granted. Henry Waxman wrote the law that puts these labels on the bag.”

Lifting a bottle of pills, she said, “Henry Waxman wrote the law that created the generic drug industry.”

Then displaying an apple, she said, “Henry Waxman wrote the law that removed dangerous pesticide from apples and other foods.”

Waxman’s career in elected office began in 1968 when, at age 29, he won a seat in the California Assembly. He was elected when Ronald Reagan was governor and the Rams still played in the Los Angeles Coliseum. When Waxman first arrived on Capitol Hill, Jerry Brown was moving into the governor’s office — for the first time.

Along with his friend and fellow lawmaker Howard L. Berman, who lost his congressional seat in 2012 to a fellow Democrat, Waxman as a state legislator forged a politically influential partnership, often referred to as the Berman-Waxman machine, that reshaped the state’s Democratic Party. Then, after six years in Sacramento, he moved to Washington.

“I hoped to be able to serve 20 years and leave a mark on some important issues,” he said in his statement. “But in what feels like a blink of an eye, it has been 40 years, and I’ve devoted most of my life to the House of Representatives.”

Noam N. Levey in the Washington bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.