Analysis: Trump wants to toughen the nation’s libel laws. Here’s why he isn’t likely to succeed

- Share via

Donald Trump hates to lose unless he wins by losing.

So, the president is quick to portray himself as a victim, especially when he thinks he has been defamed.

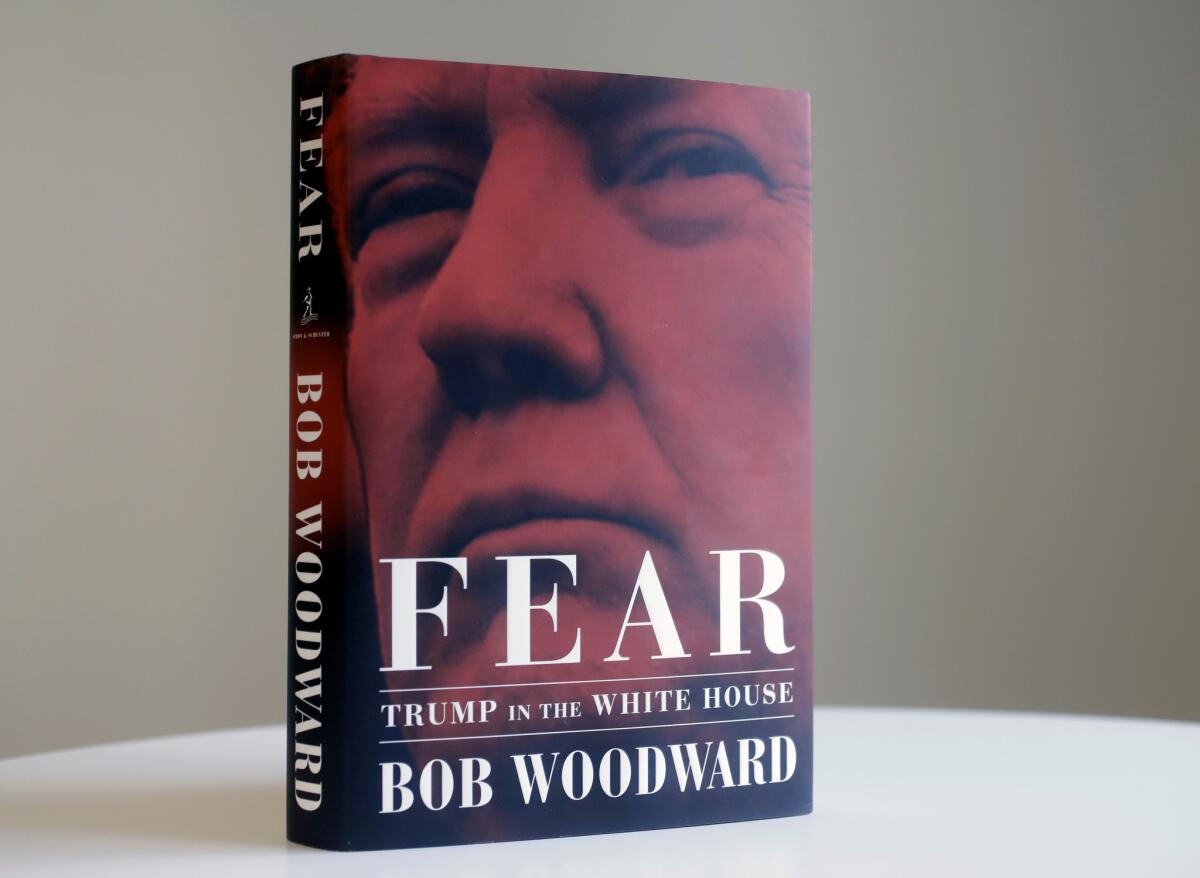

On Wednesday, in response to the publication of excerpts from “Fear: Trump in the White House,” author Bob Woodward’s new, critical book on his presidency, Trump called on “Washington politicians” to change our nation’s libel laws.

Earlier this year Trump called libel laws “a sham and a disgrace,” shortly after his lawyers had threatened a possible libel suit in an unsuccessful attempt to block publication of another book — Michael Wolff’s “Fire and Fury: Inside the Trump White House.” He then renewed his campaign promise to “open up” America’s libel laws, pledging “to take a strong look” at them.

Changing our libel laws is easier said than done and, upon reflection, Trump might not want to push for change. Neither the president nor Congress can easily change defamation laws, and Trump’s own inflammatory rhetoric would most certainly be a casualty were libel laws toughened.

Trump has never brought a successful defamation case in court. Still, his lawsuits, including litigation deemed frivolous, are an effective tool for attacking his critics, forcing them to spend lots of time and money defending themselves.

A 2016 USA Today analysis found that Trump and his businesses had been involved in more than 4,000 lawsuits over 30 years in U.S. state and federal courts, including seven speech-related actions brought against media outlets and other critics. It and a subsequent report commissioned by the American Bar Assn. showed these actions were part of a broader attack on the media that included countless cease-and-desist letters and threats of much more litigation.

The ABA report, prepared by Susan E. Seager, a Los Angeles-based 1st Amendment lawyer, concluded that four of the seven actions were dismissed on the merits and two were withdrawn voluntarily, and that Trump won one arbitration case against a former Miss Pennsylvania by default. Seager said there is some question whether the defendant paid any of the $5-million judgment against her before or after Trump’s lawyers filed a “Notice of Satisfaction” that ended that case.

Trump’s ability to change libel laws is limited by the 1st Amendment, the Supreme Court, and the fact that libel cases are decided in state courts interpreting the law of that state. The 1st Amendment prohibits Congress from passing any law that abridges “the freedom of speech, or of the press,” and the 14th Amendment extends that prohibition to the states.

The Supreme Court, in a 1964 case, laid down a “federal rule” requiring public officials to prove “actual malice” — that a statement was made with “the knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.” That landmark, 9-0 decision in New York Times Co. vs. Sullivan has been extended in subsequent cases to include “public figures” as well as “public officials.”

While the president’s most prominent libel lawyer, Charles J. Harder, has effectively used privacy laws when suing media companies on behalf of celebrities, including Terry Bollea (a.k.a. Hulk Hogan), it is difficult to see how Trump could successfully assert that his right to privacy extends to his actions in office or while campaigning.

Nor does the Supreme Court seem likely to reverse its libel rulings. Although Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in 2016, told me in a 2005 interview that, given the chance, he would have voted to reverse Sullivan, no sitting justice has voiced similar sentiments. Congress’ commitment to the 1st Amendment and that of the Supreme Court seem secure, even with the addition of a new justice to succeed Anthony M. Kennedy.

On Wednesday, Trump’s tweet asked, “Isn’t it a shame that someone can write an article or book, totally make up stories and form a picture of a person that is literally the exact opposite of the fact, and get away with it without retribution or cost.”

What Trump describes is a near-perfect definition of “actual malice,” and as such, it is already covered by the Sullivan decision. In addition, Sullivan and the precedents the court relied on in reaching its decision protect the president from suits asserting his most outrageous attacks are themselves libelous.

“Authoritative interpretations of the 1st Amendment guarantees have consistently refused to recognize an exception for any test of truth,” Justice William J. Brennan wrote in Sullivan. His opinion went on to accept the fact that politicians “at times [resort] to exaggeration, to vilification” and even to “false statement.”

Impassioned rhetoric notwithstanding, there is no reason to believe President Trump really wants to do anything that would jeopardize that protection.

Pearlstine is The Times’ executive editor.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.