Must Reads: A year after Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico still struggles to regain what hasn’t been lost for good — while fearing the next big one

- Share via

The rain falling into Bianca Cruz Pichardo’s home in Puerto Rico’s capital forms a small stream from her living room to the kitchen, past a cabinet elevated by cinder blocks.

The living room is dark, save for some light coming from the kitchen and a bedroom. The 25-year-old cannot bring herself to install light bulbs in the ceiling’s sockets because she fears being electrocuted.

For a year, her landlord in San Juan has told her he will repair damage caused when Hurricane Maria ripped through the island last September, she said, but still nothing. The worst of the rain is kept out by a blue tarp that serves as a temporary roof.

“He says, ‘This week I’ll bring the materials over,’” she said recently. “But he doesn’t do anything.”

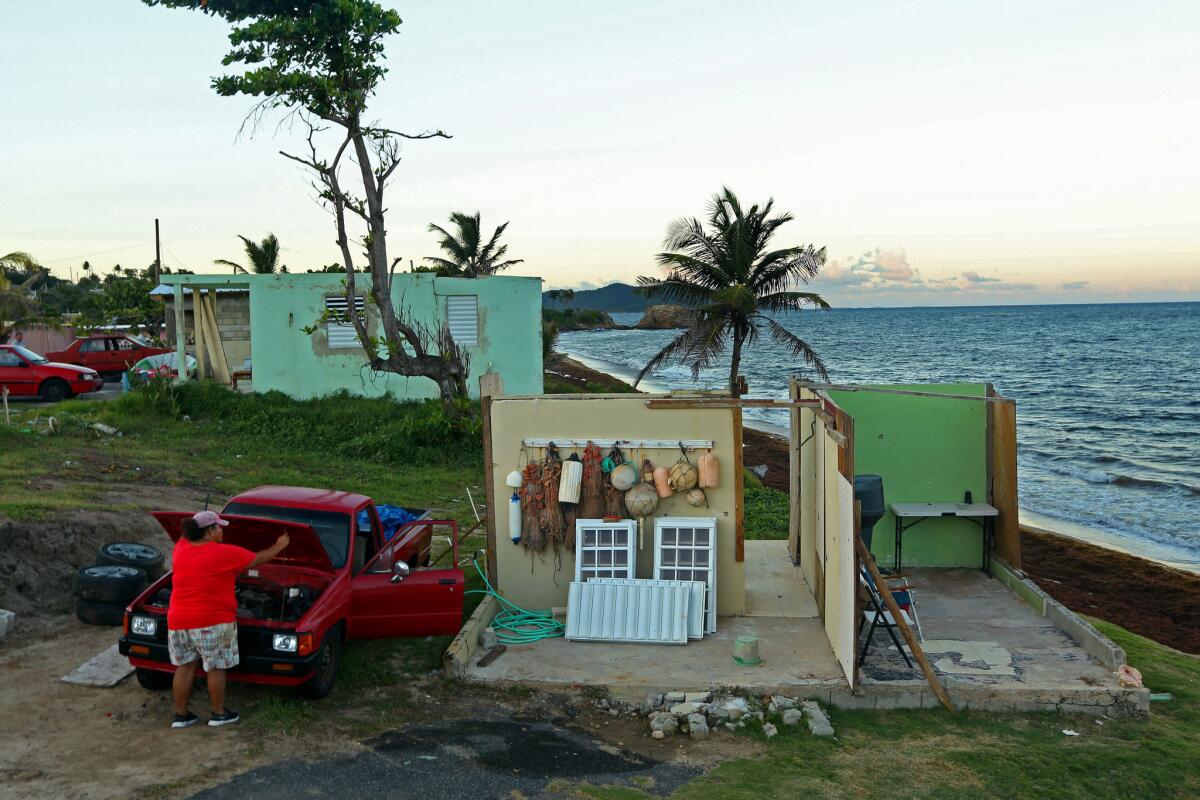

Throughout Puerto Rico, the destruction caused by the devastating wind and rain generated by the Category 4 hurricane a year ago Thursday still shapes daily life.

Thousands of families rely on the blue tarps to protect themselves and their homes while awaiting repairs, many residents face financial struggles exacerbated by the storm, neighborhoods are dotted with shuttered schools and abandoned homes, and some residents can’t help worrying about whether they’ll survive when the next storm hits.

Hurricane Maria led to nearly 3,000 deaths, sent residents on desperate searches for food, water and medical treatment, knocked out electricity in many areas for months and damaged hundreds of thousands of homes. It caused thousands of residents of the U.S. territory to move to the mainland to protect themselves and their families.

It also resulted in what federal officials acknowledged in July was an inadequate response to the emergency on the island, home to about 3.3 million people who are U.S. citizens at birth.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency, for example, found that its planning assumptions severely underestimated the devastating impact of a major hurricane like Maria. The busy 2017 storm season, which included hurricanes Harvey and Irma, also contributed to the agency’s struggles to provide food and water for Maria victims in Puerto Rico.

Local officials have not gone without criticism for the island’s outdated infrastructure and poor management, including billions of dollars of debt. The official death toll from Hurricane Maria, which held at 64 for months, was criticized as ridiculously low before a study ordered by the island’s government estimated late last month that there were 2,975 storm-related deaths.

The good news for many Puerto Rico residents is that power has been restored — though problems with the electrical grid persist, drinking water is largely available, and rebuilding is happening throughout the island. Some of the anger, frustration and even despair generated by the problems with emergency assistance have been tempered by determination.

The struggles, however, are far from over.

Cruz’s 10-year-old daughter watched the water fall from the ceiling.

“It’s dripping here, here, here, here,” she said, walking through the living room and into the bedroom she shares with her younger sisters. Pieces of ceiling have crumbled away, and the paint on the walls has peeled and bubbled from the water.

About three months after the storm, Cruz, who has four children, ages 2 months to 10 years, qualified for $900 in disaster assistance from FEMA to replace what was lost in the home.

The money paid for new furniture, and clothing and shoes for her girls, she said. The family, meanwhile, struggles to cover rent, food and basic necessities and cannot move, she said.

Her daughters’ elementary school, which was around the corner from their home, closed after the storm — part of an effort to address declining enrollment worsened by Maria and budget issues — so they walk across the neighborhood to another school a little more than half a mile away.

Around the corner from Cruz’s home, Flor Idalia Morell, 74, used a solar-powered lamp the size of a small gift box to light the only part of her home that remained inhabitable after Maria — a single room on the first story that once belonged to her mother-in-law. The lamp casts a soft glow that changes color from red to green to blue to yellow. Rainwater dripped in a corner of the room.

Morell was on the second floor of the home when Maria came. She held a framed image of Jesus Christ to her chest as the storm tore the walls away, she said.

“It didn’t break,” Morell said with a laugh, pointing at the frame, which now hangs on a wall.

Her home is too damaged to restore electricity. She doesn’t have a mattress, so she sleeps on a plastic beach chair. She doesn’t have a refrigerator, so she keeps bottled water in a cooler.

The second floor has been replaced by a wood frame covered in a blue tarp that she says FEMA workers installed for her. Water still comes in, so when it rains and she needs to cook, she puts an umbrella over the gas stove.

She’s not sure where she could possibly get enough money to fix the home.

About 45 miles southeast of San Juan, in the small town of Yabucoa, a tangle of vines invaded Angel Berrios Cintron’s rusted plow, where it sat unused at the entrance to a three-acre farm plot he had rented before the storm.

The equipment has been there since Maria, which made landfall in the eastern region of the island, tore the roof off Berrios’ home nearby, destroying everything inside. The storm turned the yams and plantains he had been growing into a pile of upturned plants that rotted in the sun.

After Maria, Berrios said, he had to choose between rebuilding his home or replanting his crops. He did not have enough money or time to do both, so he picked the home.

“Everything is lost. It’s all wild now,” he said, waving at the overgrown farm.

At the edge of the property, someone else had planted a row of yams and other plants. Berrios walked over to them, pulled at the weeds and dusted the soil with his hand, unearthing a yam.

“I survived off this land,” he said.

In the days after the storm, Berrios, 65, and his wife, Migdalia Lazu, 54, moved into their 38-year-old daughter’s home. They slept under a blue tarp on a mattress on the floor, using a barbecue to cook because they did not have electricity. At night, they used a generator that cost them $15 a day in gasoline, to power fans to ease the heat and keep the mosquitoes away.

It seemed as if every living thing was desperate in those days, Berrios said, even the rats, which invaded their home and ate the electrical wiring.

“For your life’s work to go like that, in a flash, and for you to be left with all your debts, not having enough to protect your family. I don’t wish that on anyone,” he said. “It takes you to such a faraway place.”

In late October, the couple left for Allentown, Pa., to live with their younger daughter and her two young children. But the winter was hard on them, and they only grew more desperate to begin fixing their home.

They returned in March. Before the storm, Berrios had taken out a $25,000 loan to buy a bulldozer, thinking he would start clearing land for other farmers in the mountains. Instead, he is using that money to fix his house, along with $4,500 in disaster assistance from FEMA.

Berrios has replaced his roof and rebuilt much of the bathroom and three bedrooms. The house was sanitized with the help of a nonprofit group, though none of their furniture was salvageable, he said.

If he can hire contractors — he said they are in short supply — he thinks the rest of the house might be ready in six months.

By sometime next year, he said, he hopes to farm again.

Nerybelle Perez, 61, a professor at the Pontifical Catholic University of Puerto Rico at Arecibo, lives in fear of what will happen when another big storm hits Puerto Rico.

Her 96-year-old father had lived alone in the town of Cabo Rojo, on the southwest coast of Puerto Rico, before Maria. Though elderly, he was active, farming and giving cuatro lessons — the Puerto Rican guitar-like instrument — on Saturday mornings.

The storm left him without running water or electricity and destroyed his farm. Eight days after Maria, he started feeling pains in his chest. Local doctors put the two of them in an ambulance and sent them to a hospital in San Juan, where he was turned away, she said.

“The doctor told me, ‘I can’t help you. We don’t have water. We don’t have power. ... Your father is old. He has lived the life he is going to live,’” she said.

The ambulance made its way back across the island, and her father died on the road. Perez, who lives near San Juan, said she has no doubt the island will be left without power when the next big storm comes.

“Of course it’ll happen again,” she said.

The combination of Hurricane Irma, which skirted Puerto Rico in early September, and Maria, which followed two weeks later, destroyed the island’s long-neglected electrical grid, which had been problematic but somehow managed to provide energy to residents.

Without power, schools, businesses and hospitals closed; the cost of gasoline for generators ate at families’ incomes; and the sick whose conditions required refrigerated medications or special equipment were left in dire conditions.

It wasn’t until August that the utility said power had been fully restored. But it is common for people to lose power for prolonged periods of time.

After Hurricane Maria, Elena Rivera de Jesus, 72, waited 10 months for utility workers to restore power to her small cliffside home in the mid-central island mountain town of Adjuntas, where the hills are growing rich with tropical plants.

Rivera last week stood on a pathway outside her home and pointed to a downed power line nearby. She did not know what caused the line to fall or when it might be fixed.

“We haven’t had power here for 15 days,” she said.

She has been caring for her bedridden husband for five years, since his legs were amputated because of complications with diabetes.

She walks down the mountain into town when he needs medicine, bathes him with water poured gently over his shoulders, and whispers in his ear to keep him engaged.

“Who do you belong to?” she asks. On a good day, he responds: “To you, with all my heart.”

When the power was out and her husband’s insulin needed to be kept cold, her adult children who live nearby brought ice and she packed it in a cooler. Eventually someone loaned her a generator, but the cost of gas and its deafening noise made it impossible to use regularly.

In March, Rebecca Rodriguez, who works with the local nonprofit organization Casa Pueblo, brought Rivera a solar-powered generator that allows her to give her husband his breathing treatment every six hours and use an electric air mattress that prevents bed sores.

Now the organization is paying to install solar panels on the couple’s home, an alternative to the unstable power grid and an example of how island residents and others have helped during the crisis. The funding came from donations received after the storm.

“The government isn’t doing this,” said Alexis Massol Gonzalez, the group’s director, “the community is.”

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.