50 years after King’s death, struggles remain for African Americans in Memphis

- Share via

Reporting from Memphis, Tenn. — Half a century after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., Room 306 of the Lorraine Motel looks almost the same as he left it.

The bedspread on King’s bed is folded back. A Bible sits on the night stand, and coffee cups, ashtrays and plates of half-eaten food are scattered across the room, which is now part of this city’s National Civil Rights Museum.

As tens of thousands of people make pilgrimages to Memphis this week to this sacred civil rights spot to commemorate King’s death and celebrate his legacy, many are confronting a question: How far has Memphis and the nation moved forward?

“Here we are 50 years later, and not much has improved,” said Bobby Rogers, a 39-year-old electrician from South Los Angeles, who stood in the motel’s former parking lot one day this week with delegates from his local union, gazing up at the balcony where King was shot on April 4, 1968.

“Memphis is still poor and people are still fighting for a livable wage,” he said as throngs of families, pastors, activists and union workers lined up outside the museum. “We still have so much to do.”

RELATED: Thousands gather in Memphis to remember Martin Luther King Jr. »

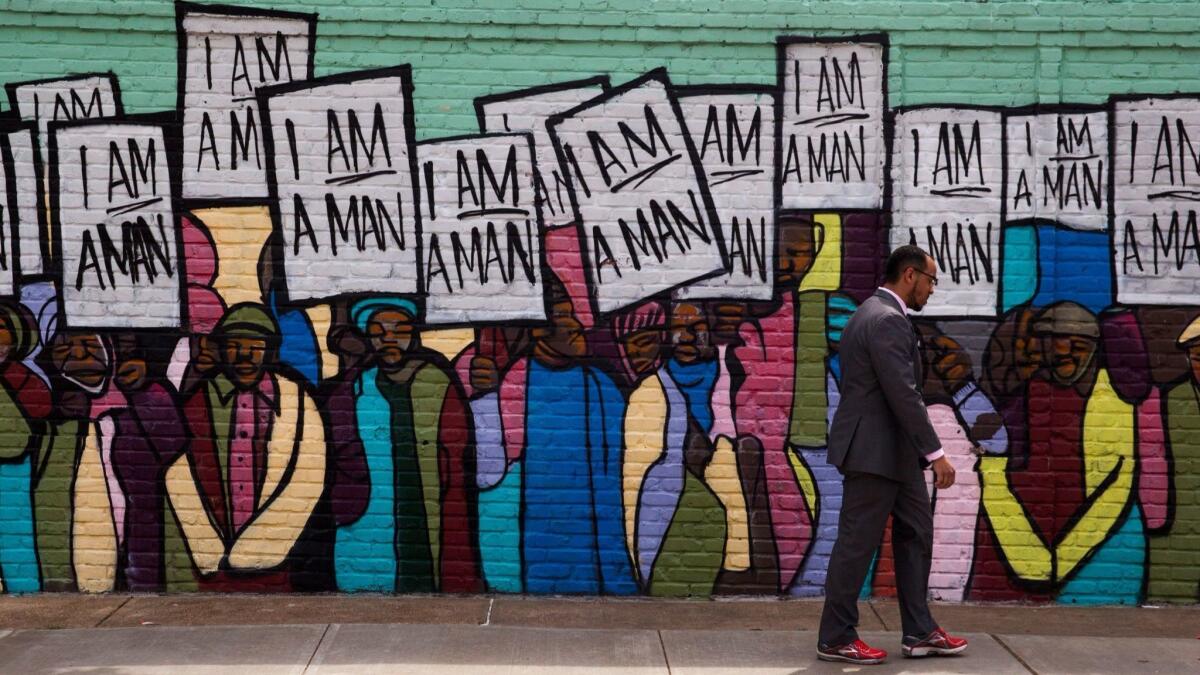

Five decades after King launched his Poor People’s Campaign and came to Memphis to support striking sanitation workers, this majority-black Southern city is the most impoverished metropolitan area in the nation, with nearly 20% of residents living below the poverty line.

Blacks in the city of Memphis suffer disproportionately, with a median household income of about $31,000 — barely more than half that of whites, according to census data. More than 52% of the city’s black children live in poverty.

“The phrase that keeps knocking around in my head is ‘unfinished business,’” said Charles McKinney, chairman of Africana Studies and associate professor of history at Rhodes College, a private liberal arts college in Memphis. “The city and the Chamber of Commerce and economic leaders brag about the low wages you can pay your workers if you come to Memphis. Economic inequality still haunts the city in much the same way that it did in 1968.”

Related: 1968: A timeline of anger, grief and change »

In the years after King’s assassination, Memphis slid into decay.

The Lorraine Motel, a source of shame for many as the site of King’s murder, became a dilapidated hub of prostitution. Manufacturing jobs across the city ebbed as a wave of major companies, such as Firestone and International Harvester, closed plants in the 1980s.

Many Memphis workers now have little choice but to make ends meet with temporary, part-time jobs that offer low pay and no benefits. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, Shelby County, which contains Memphis, has one of the highest concentrations of temporary workers in the nation.

As the city has struggled with a dwindling population — from 691,210 in 2000 to 646,889 in 2010 — it has also suffered a rise in crime. In 2016, the year Nashville overtook Memphis as the biggest city in Tennessee, Memphis experienced a record of 228 homicides. The vast majority of victims were black.

“Our city has actually gone backward,” said Keedran Franklin, 31, a local hip-hop artist and organizer with Memphis Coalition of Concerned Citizens, a nonprofit group that unites grass-roots activists to advocate for poor and minority residents.

Though blacks make up 64% of the city’s residents, he said, they continue to be treated as a minority and “tricked out of economic justice.”

A lot of people who left places like the Firestone plant making the equivalent of $13 or $15 an hour are now working part-time for FedEx, the city’s largest employer, for lower wages, said Franklin, who has worked as a community organizer for the Fight for 15 “living wage” movement. “And at four hours a day, that’s not enough to eat.”

While many of the younger generation of activists present a grim assessment of the last 50 years, some of their forebears note progress, along with setbacks.

RELATED: How 1968, a year of tumultuous events, continues to shape our world »

“If I see King again, I would like to give him a report card,” said the Rev. Jesse Jackson, 76, the civil rights activist and one of the last remaining eyewitnesses to King’s shooting.

First, Jackson said, he would tell King that state legislatures have been desegregated, that industry has spread across the South, and that multiracial relationships are now common, even in the Deep South. A black man was even elected president of the United States. But he would also let King know his crusade against poverty remains unfinished.

More than 40% of American workers make less than $15 an hour, with the burden falling heavily on blacks and Latinos. The median net worth of white families is more than 10 times that of African American families.

“More and more got less and less,” said Jackson, who visited the Lorraine Motel this week. “King’s agenda is as relevant today as it was then.”

Amid stagnation in Memphis, there have been glimmers of change. In 1991 — the same year the city elected its first black mayor — the Lorraine Motel reopened as part of a massive downtown civil rights museum. While many nearby storefronts are boarded up and some streets remain empty for blocks, a smattering of boutiques, gourmet coffee shops and barbecue joints has opened downtown, although often they cater mostly to tourists.

On Tuesday, the Rev. William Barber, a minister known for his Moral Monday movement in North Carolina, took to the National Civil Rights Museum to detail his plan to reignite King’s Poor People’s Campaign in May with 40 days of nonviolent action in Washington and across the country.

At the same time, a younger generation of local activists, part of a burgeoning movement that has stepped up in recent years to challenge police brutality and advocate for higher wages, held rolling block parties across the city.

“There’s a lot of struggle going on in Memphis, but also a lot of folks who are up for the challenge,” Franklin said, noting that many younger African Americans were mobilizing around the Coalition for Concerned Citizens, Fight for 15 and Black Lives Matter. “People have seen a marked deterioration in their material well-being.”

Many younger activists say it is time for a new generation of African Americans to revive calls for economic justice in Memphis.

“It hurt so many people psychologically for Dr. King to have been killed here,” said Tami Sawyer, 35, a director of diversity with Teach for America Memphis. “So it was easy to say, ‘OK, let’s wrap this up’ and push away the conversation and have this Kumbaya moment. But we can’t be afraid of the conversations we need to have for a radical redistribution of power.”

Sawyer, who led a successful campaign last year to take down two Confederate statues in city parks, now plans to go beyond protesting and writing letters.

This year, she is running for Shelby County commissioner on a platform of challenging poverty and unemployment.

“The last words King gave publicly were a challenge to us in Memphis to shake up economic and political power,” Sawyer said. “It is time for us to actually live in that challenge. We don’t have another 50 years to be asleep and not live the change that he came here and died for.”

Jarvie is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.