A city in mourning: With many services, Dallas buries its dead

- Share via

Reporting from Dallas — After the shock and amid the grieving, Dallas paused Wednesday to bury its own.

Three of the five officers killed in last week’s downtown shooting were remembered during a day of mourning that drew friends, colleagues, family members and police officer from across the country.

The back-to-back-to-back services stretched schedules throughout the city.

The mayor planned to attend two; the Dallas police chief said he was going to all of them.

The police choir was torn. Family of Dallas Area Rapid Transit Police Officer Brent Thompson, 34, requested it perform at 10 a.m. But the service for Dallas Police Senior Cpl. Lorne Ahrens was at 11 a.m., half an hour away. Ahrens’ family said they understood, and the choir hoped to make it to the cemetery to see him laid to rest.

The police force was also short-staffed. There was a private funeral for Sgt. Michael Smith, 55, at 10 a.m., with a public service at noon Thursday. Services for Officer Michael Krol, 40, were set for Friday; Officer Patrick Zamarripa, 32, for Saturday. So many police were attending the simultaneous funerals, stations around the city had to cover one another’s shifts.

Officers streamed into the stadium-sized Prestonwood Baptist Church in dress uniforms with patches from Chicago, New York, Seattle, Los Angeles.

Ahrens, 48, was killed last Thursday while patrolling a protest march, an attack that killed five officers, wounded nine and rattled the nation.

A Los Angeles native, Ahrens had worked as a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s dispatcher, and 28 of his old co-workers attended the funeral, most in uniform.

Los Angeles Sheriff’s Det. Sgt. Ed O’Neil, who played football with Ahrens on the Southern California Blue Knights, wore his old jersey to the funeral and brought a helmet that he placed near Ahrens’ open casket.

That’s when he noticed Ahrens wasn’t wearing his police uniform. His old friend had wanted to be buried barefoot in a T-shirt and shorts. Fitting, O’Neil thought.

As he approached to pay his respects -- near where Ahrens’ wife and two children, ages 8 and 10, sat -- he said he also thought, “I don’t know if I can do this.”

He and the others were tearing up. But then he thought of Ahrens, how, “in our group, if it would have happened to any of us, he would have done anything to say goodbye.”

As the crowd grew to about 5,000 people, most in uniform, Ahrens’ pastor rose to make a request.

“I’m going to ask you to take off your badges, to take off your stripes, to take off your position,” he said. “Allow yourself for a little while to be human, to be a person, to be a husband, to be a wife, to be a mother, to be a father. And to allow yourself to feel.

“No chain of command,” he added, “no higher authority, just flesh-and-blood human beings.”

And so they did.

Two Dallas officers who worked with Ahrens shared stories of his supercharged exploits, how the “gentle giant” who stood 6-foot-5 and weighed 300 pounds ripped the bars off a drug house window during a bust and stomped fences as he chased suspects.

He was the guy you wanted as backup, they said, a “supersized can of kickass” who the day before he was killed bought a meal for a homeless man.

Officer Eddie Coffey recalled how enthusiastic Ahrens was when he arrived at the academy in 2002.

“Later I found out he was sleeping on the floor of his apartment,” Coffey said, so he gave him some furniture and a bed, and Ahrens was overjoyed. “You would have thought I had hung the moon,” he said.

That’s how a self-described “corn-fed country boy” wound up friends with Ahrens, a “heavy metal-listening tattooed city boy.”

Ahrens met his wife, a Dallas detective, on the job, and tattooed one of her love notes on his neck, lipstick kiss and all.

“He wanted to be the first at every call, especially the hot ones,” Officer Debbie Taylor remembered.

“Nothing brings compliance as quickly as Lorne unfolding himself from a squad car,” she said.

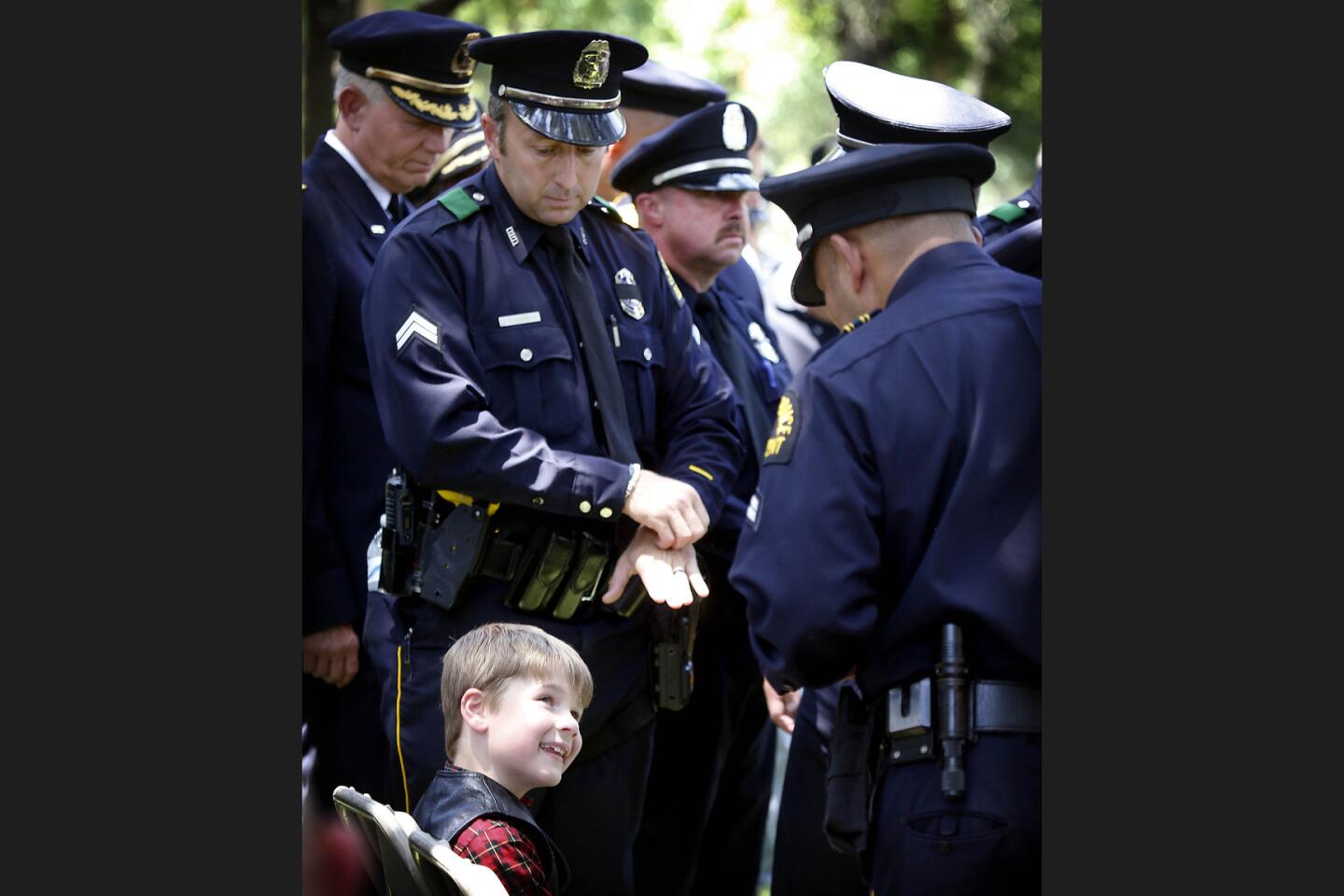

She recalled a domestic-violence call they rolled on, how they entered the house to find a child crying, scared, and suddenly facing this huge uniformed stranger.

“Lorne knelt down so he was eye level with the child. He spoke to him, and within minutes had the boy smiling and laughing,” she said.

Ahrens’ casket left the church accompanied by a procession, scores of police cars and motorcycles that all but shut down the route.

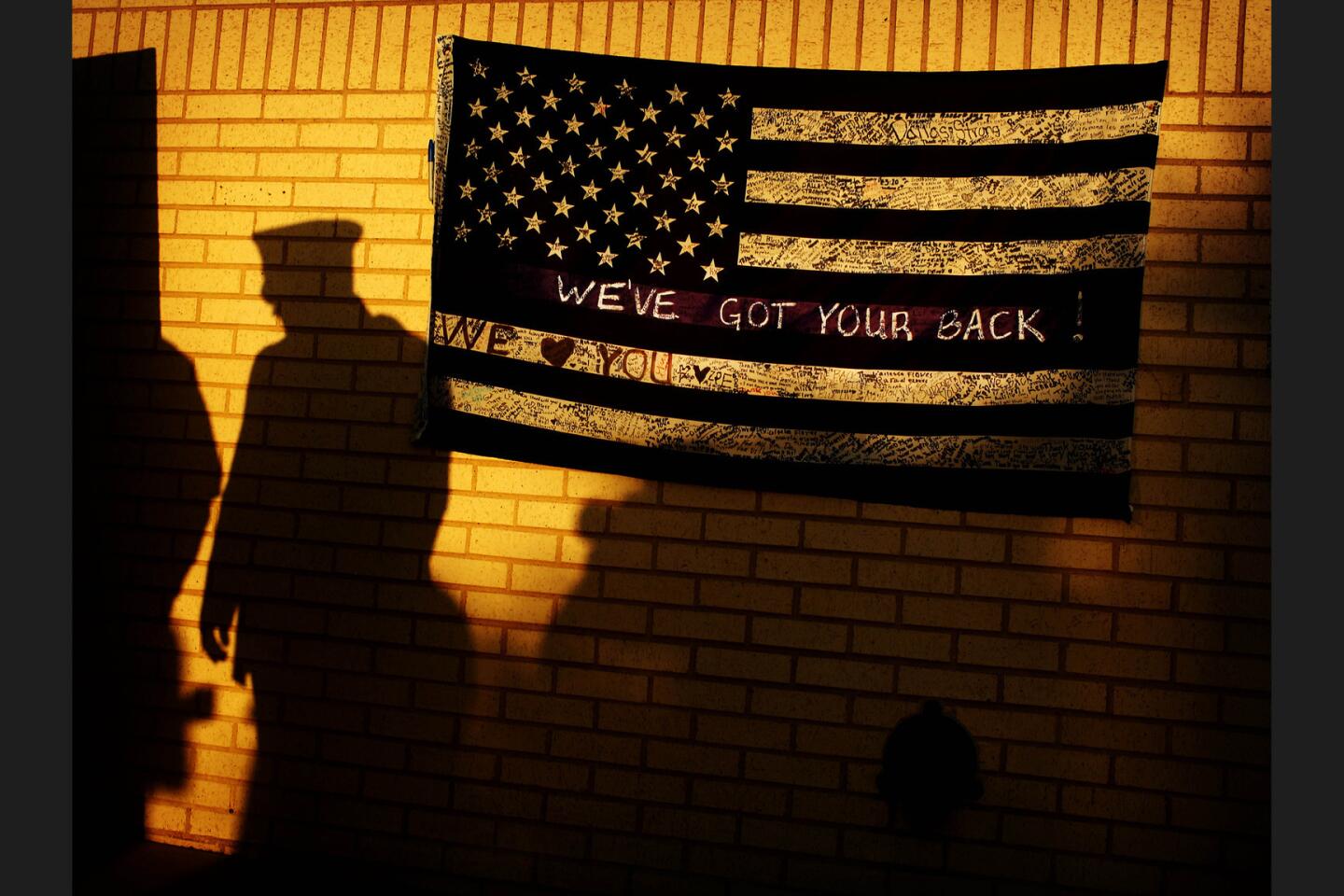

Inside one of the cars was Ron Pinkston, president of the Dallas Police Assn. He gazed out to see bystanders gathered at the roadsides and overpasses.

“It was heartwarming,” he said. “...Seeing people saluting, hands over their hearts, all races.”

Ahead of the procession, the police choir arrived at the cemetery from Officer Thompson’s funeral, where it sang “I’ll Fly Away.”

“It’s exhausting,” Senior Cpl. John Hepworth, the acting choir director, said of the multiple funerals.

Jim Hill, 82, was waiting with the crowd, having driven 15 hours from Ohio to see his niece, Ahrens’ mother. He had not seen Ahrens since the officer was a child, but he wanted to help bury him in the “garden of honor” plot dedicated to civil servants killed in the line of duty.

“It’s a sorrowful thing,” he said.

When the family arrived, Hill sat by Ahrens’ mother’s side as the honor guard fired rifles and delivered her a flag. Scores of police stood at attention throughout, the cemetery hushed as wind stirred the canopy of oaks.

Finally, an officer announced that they were dismissed, and they relaxed – for the moment.

They still have more funerals to go.

ALSO

From Ferguson to Baton Rouge: Deaths of black men and women at the hands of police

After 45 years, the FBI finally throws in the towel on D.B. Cooper hijacking

Obama mourns slain Dallas officers: They ‘shared a commitment to something larger than themselves’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.