What former President Carter can expect in his cancer treatment and prognosis

- Share via

As doctors learn more about the cancer that has spread through his body, former President Jimmy Carter will weigh treatment options that most likely will not cure his disease but could prolong and improve the quality of his life.

Carter, 90, hasn’t revealed many details about his medical condition. That may be because he doesn’t have much information yet, physicians said.

On Aug. 3, doctors at Emory University Hospital in Atlanta removed a mass from his liver. At the time, the former president’s press office reported that his prognosis was “excellent for a full recovery.”

But in a short statement issued Wednesday, Carter said the situation had changed.

“Recent liver surgery revealed that I have cancer that now is in other parts of my body,” he said. “I will be rearranging my schedule as necessary so I can undergo treatment.”

Carter said that he would make a more complete public statement when more facts were available — possibly next week.

In the meantime, experts say, Carter’s medical team is probably conducting a battery of tests to characterize his tumors to help determine the best course of treatment.

“The initial part of the journey will be finding out where this came from and where it spread to,” said Dr. J. Leonard Lichtenfeld, deputy chief medical officer for the American Cancer Society. “We know it was in the liver and it’s gone elsewhere, but we don’t know more.”

Lichtenfeld said evaluations could include blood work, body scans and microscopic and genetic evaluation of tumor tissue to figure out where in the former president’s body the cancer originated.

Knowing where the cancer emerged will help doctors figure out what options they have to combat the disease — whether they will be able to cure it, stall or slow its growth, or otherwise palliate whatever symptoms Carter might develop as it runs it course.

Of particular concern for Carter is pancreatic cancer, which has been widespread in his family. The disease, diagnosed in nearly 1 in 50,000 Americans every year, is difficult to detect in its early stages and is almost always fatal.

Even when diagnosed early, fewer than 15% of people with pancreatic cancer survive five years or longer, according to the American Cancer Society.

Carter’s three siblings and his father all died of the disease.

“They’ve lived this too many times,” Lichtenfeld said of the family. “The president has shared that he was under surveillance for pancreatic cancer. Whether that had a role in finding this lesion is unknown to me. Pancreatic cancer would be on anyone’s list when you hear about tumors in the liver.”

Dr. Stephen Gruber, director of the USC Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, agreed that pancreatic cancer seemed like a possible cause, but cautioned against concluding prematurely that Carter’s cancer was caused by genetics.

While cancer-causing genes do seem to run in the former president’s family, he may not have inherited them.

“Furthermore, genetics is not destiny,” Gruber added. “Just because you have a gene, you don’t always get a disease.”

He said that inherited forms of cancers often strike early. A Times obituary for Carter’s sister, Gloria Carter Spann, noted that the president’s close relatives who died from pancreatic cancer all succumbed at relatively young ages, between 51 and 63 years old.

“It’s not easy to tell from the information that is publicly available if his cancer is attributable to a genetic cause,” Gruber said.

Once Carter’s doctors understand where his cancer came from and how far it has spread, they’ll start discussing treatments with the president and his family, Lichtenfeld said.

Options could vary from “intensive systemic to localized systemic to nothing,” he said — meaning that the team may decide to use chemotherapy to attack cancer throughout Carter’s body, may opt for strategies like surgery or radiation to remove it in specific areas, or may leave tumors alone if they aren’t causing symptoms or if the effects of treatment would do more harm than good.

“There’s a balance to consider,” he said, noting that intensive medical treatments like chemotherapy can be destabilizing in older patients, but that advanced age does not rule out the possibility of treatment as it might have in the past.

“It’s not the years on the calendar. It’s the biology of the person,” he said. “We have to pay primary attention to the person … and what will provide the best quality of life under the circumstances.”

Dr. Yuman Fong, chairman of the surgery department at City of Hope in Duarte, says patients he has worked with had strikingly individual goals toward treatment. Some, confronted with a spreading cancer, choose aggressive therapy. Others want to spend as little time with doctors as possible.

“It depends on the individual and what’s available to them,” said Fong, who specializes in treating liver and pancreatic cancers.

If the president’s cancer is found to have originated in the colon, his prognosis will be better than if it originated elsewhere in the body, he said.

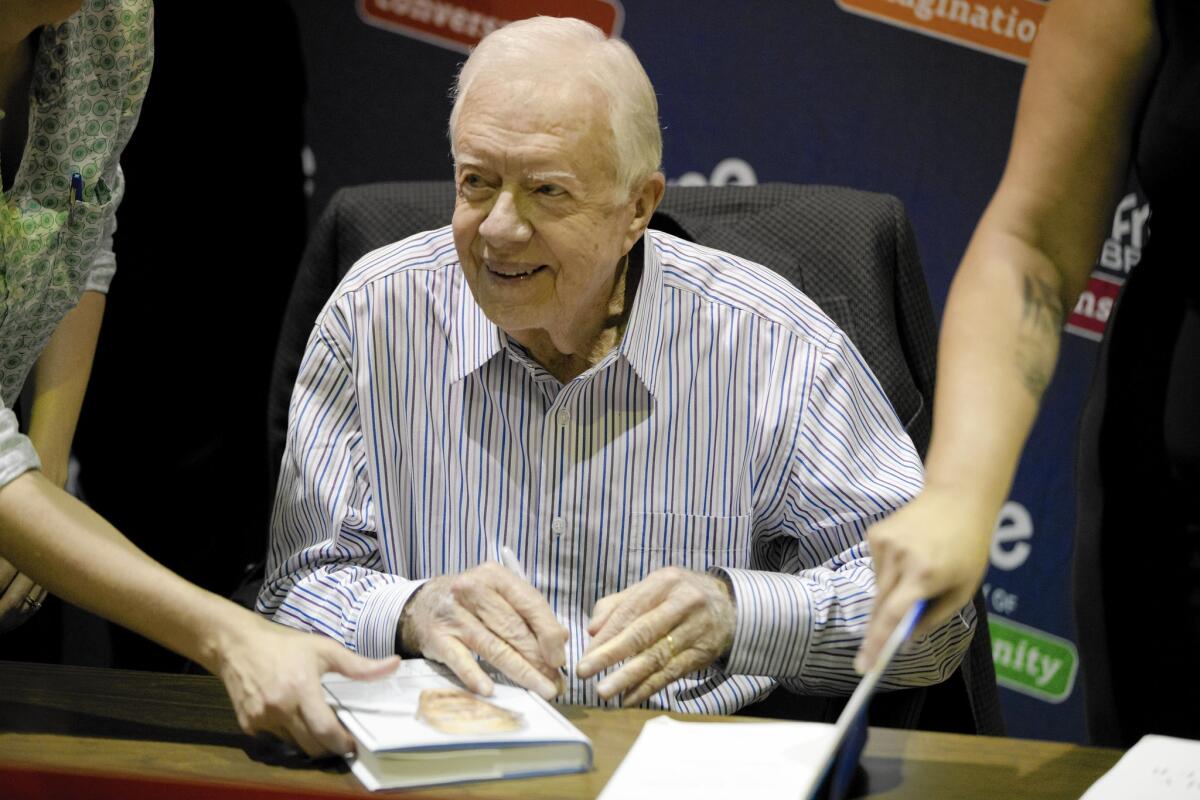

Fong, who called Carter “a very vigorous 90,” thought he would be a good candidate for an experimental cancer treatment in the early stages of testing.

“Solutions come from brave people who try early drugs,” Fong said. “Given his record of service, I’ll bet you he will enter clinical trials to develop new medicines to help the next generation of individuals.”

Twitter: @LATerynbrown

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.